Reuven Namdar

It happened during the big break.

My classmates ran amok on the sports field, kicking the ball and yelling football terms at each other that they had heard on the radio show "Songs and Goals" that was broadcast every Saturday.

I was not attracted to the field.

I was happy to leave behind me the noise, the blinding Jerusalem light and the heat-scorched air and be swallowed up in the comforting gloom of the library.

I loved the monastic, dusty space: the rows of gray metal pages, the golden light that filtered through the curtains, the books whose colorful covers were covered with a thick layer of nylon, and the absolute silence maintained by the librarian whose name I had long forgotten - a librarian who for some reason brightened my face, despite the image The tough one she was attached to at school.

This time, too, I chose a book almost at random: the collection of poems "Incarnation" by the poet Dan Pegis.

I plunged into it - immediately losing the sense of time and space - but this time it was especially difficult for me to detach myself from the book, when the shrill ringing of the bell disturbed the peace of the library and brought me back to reality.

I looked around me as if I had woken up from a particularly intense dream, and without thinking much I opened my satchel, slipped the book into it and quickly left the library - trying not to make eye contact with the librarian.

The thin book rested on my lap, under the desk, for the rest of the school day.

I flipped through it quietly so the teacher wouldn't feel it - excitedly sampling song after song and admiring the delicate, precise cutting of the words, and the elegant spaces of silence stretched between them.

I continued to read it on the way home, being careful not to bump into the pillars and the stone fences by the side of the sidewalk.

I finished it in the evening and put it on the shelf, determined to secretly return it to the library - which, of course, didn't happen.

As usual, I read it over and over, several times, internalizing and assimilating it into me, until I felt that it had become an inseparable part of me.

It stayed on the shelf for years, giving me a slight pang of guilt every time my eye flickered over it.

The years passed, I finished school, and the librarian also probably finished her work and retired.

One evening, at some literary event, I recognized in the audience the poet Dan Pegis - the one whose book I borrowed without permission from the school library.

I hesitated a little, and finally decided to introduce myself and confess to him my distant literary crime.

A sly-ironic glint flashed in his eyes.

"Listen," he told me, "this is the greatest compliment a poet can hope for."

Asaf Gavron

There is a good chance that my memory is playing tricks on me, but right now he insists that on Sunday afternoons the mobile library and the ice cream truck would come together to our settlement, Moz Ilit, and stop side by side.

The ice cream truck had its own tune, but we didn't need to hear it to leave the houses.

because we went out before that to wait for the library, which always arrived exactly on time, 5:30, or maybe 6. It was the library of the regional council, and like the buses that took us to school every morning, it was yellow: a kind of big van, really big, almost the size of a bus Or a truck, the back of which was like a living room with shelves upon shelves, with books upon books.

The library used to stop at the bottom of Sderot Rishonim, next to the colorful wooden bench, in front of the public telephone above the kindergarten, below which is the public shelter.

In the back wall of that living room, which was located in the back of the huge van, a door opened, and from it opened folding stairs, on which we would go up, into the library, and smell the books, and touch them, and search, and pull out, and flip through the pages.

Every week each person was allowed to take one book, that's what I would do, but some were more sophisticated than me, like my friend Yariv, who changed a book for each of his brothers and also his father, and read five books a week like that, which many times wasn't enough for him.

We all exchanged books every week.

all boys

and all the girls

Our whole cycle, the whole cycle below us, the whole cycle above us.

We read all of Hasamba like that. We read all of the Secret Seven and the Five. Our name was on the card that was in an envelope that was glued to the inside cover, and we took it home, and read all week, and the next Sunday we came back, and waited for it to arrive, and switched to the next book.

On second thought, maybe the ice cream truck was unrelated.

Maybe he arrived on another day, Tuesday maybe?

And maybe we did hear his tune and went outside, and maybe he even stopped in other places in the settlement, and not there, near the colored bench and the payphone and the kindergarten and the public shelter, like the mobile library.

to Shoham destination

And the days of Corona.

The busy and bustling streets of Tel Aviv became empty.

Instead of going out, traveling and traveling to far away places, we were besieged in D'Emot, limited by orders and laws, wearing masks, sitting in front of the television that never stopped blaring reality.

The world closed in on us and reduced the breathing space.

And suddenly we got a message from the library.

Although the entrance to it is prohibited, it will not be possible to receive an audience until further notice, but a surprise: you can order books.

"I will make them for you in a bag and place them outside the library," wrote the librarian, as if she were running a bakery.

For us, this message was as if a hand was extended from another reality, an invitation to go out into other spaces of freedom, of imagination, of clean air without viruses, of people meeting without masks, without fears.

We chose books about travels, and sent a request.

The truth is we were skeptical.

It seemed that nothing was working in the country, so rather the services of a library?

But when we got to the library, there was a bag of books waiting for us, as if there really were hot rolls, and even a chopper - two books that we didn't ask for, but the librarian, who knows the children's tastes, thought they would like.

And also a handwritten note with a personal dedication.

Although the city is big, the library is a neighborhood one.

The television continued to distort reality, the orders with prohibitions continued to parents and staff, but thanks to the library and the dedicated librarian we could for a few hours sail to a different reality, remember what happened and hope that, as the librarian wrote, "quiet days will come".

Little did we know then that when the calm came, it would only be a respite before a new storm.

Roll Ron-Feder-Amit

Behind the counter the librarian comes out to me.

Before the meeting with the readers begins, she wishes to whisper to me: "Pay attention to the boy with the blue shirt who is sitting in the chair closest to you, on the left. Later I will explain to you why."

I stand in front of the readers, share with them my writing process, and notice the boy with the blue shirt.

When I get to the questions, he has an unusual question: Do I think my stories help children with similar problems to those of the protagonists to deal with?

I don't need a hint sent by the librarian to guess that this child has problems.

At the end of the meeting he was the last one left and approached me.

From his words it becomes clear to me that he is a beaten child.

"Everyone thinks that beaten children have a criminal father," he tells me, "but my father is a respectable man, he goes to work every morning dressed in a suit and tie, and has a driver waiting for him in the car. But in the evening, when my father discovers that I have not progressed enough in the sport he instructed me to, He beats me with a belt. Can you write a book about a boy like me?"

Tears appear in the librarian's eyes.

After the boy leaves, I find out that she was the only one in the world that the boy trusted and shared his pain.

He didn't tell the teacher anything.

Neither does the consultant.

Not even for grandpa and grandma.

Only for the librarian.

Because she was the one who knew which books he preferred, and she was the one who talked to him about his preferences.

After that meeting, on the way home, the book was already born in me which was published under the name: "Just not in the belt".

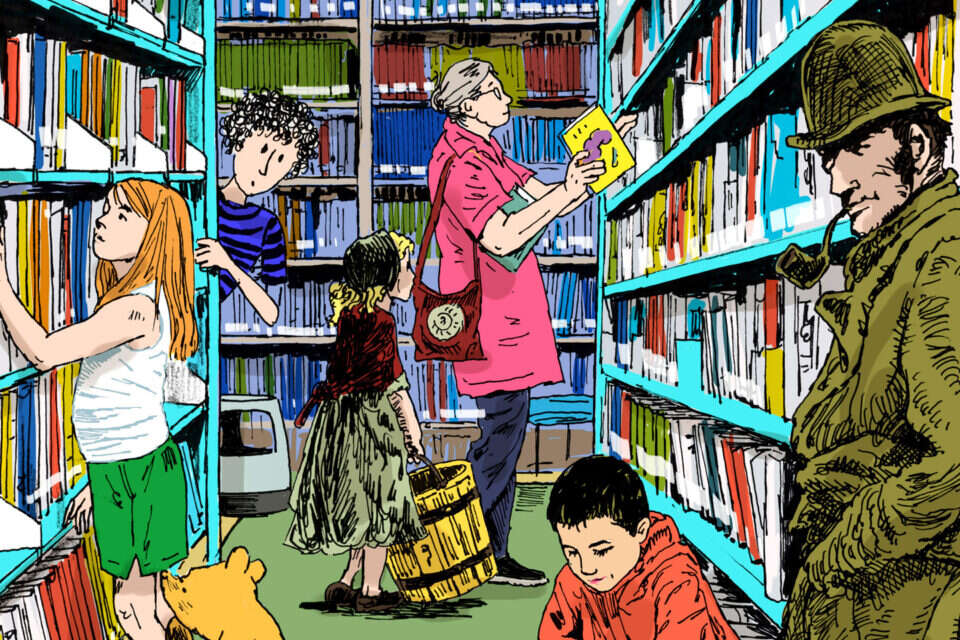

., Photo: Illustration: Ruth Goili

Yaniv Itzkovich

Three things my mother forbade me as a child.

The first prohibition - not to urinate in the pool - was due to hygienic reasons (to which a severe warning was added, regarding a special substance that dyes the urine black).

The second prohibition - not to copy in tests - had a moral reason (in my mother's opinion, it is better to be considered a fool than a liar).

The third prohibition - not to steal books from the library - was never justified, beyond the obvious point that stealing is not allowed.

But I knew that he was related to her good friend Galia, the city librarian, who often complained to her about the numerous book thefts.

"And they would have stolen Kastner or Lindgren anyway," she would grumble to my mother, "but these, lacking in culture, only have Carmeli and Mosinson in mind."

While I violated the first and second prohibition unwittingly, and at a relatively young age, I did not feel the need to violate the third prohibition.

Every week I would pick up another book from the "Secret Five" or "Secret Seven" series, read it with half interest and return it to Galia with a short nod.

She in turn would look at me with a certain disappointment, move the book to the "returned" cart and wait to sign the Enid in my next Leighton.

But once she put Victor Hugo's Les Miserables in my hand and said, "It's time you read a real book."

The act was suspicious to me.

I felt my mother's dresser above, and yet I took the book home.

And here, within a few pages I found myself plunging into the world of Jean Valjean and Cosette, filled with rage towards the included Thanardia, pitying Fantine, adoring Marius, and waking up in the middle of the night from nightmares where the dark Javert is chasing me.

Until I was notified to return the book, I did not return to the library.

And when Judgment Day came, I couldn't bear the sight of it on the "returned" shelf, the first place that book buyers approach.

It was my book, and no one was allowed to touch it.

The first book I really read in my life, and the only one until then that made me understand the power of literature.

There is no special substance in the pool that colors the urine black.

And in the tests I already copied quite a bit.

Now I have no choice but to break the third prohibition.

When I left the library it seemed to me that Galia's eyes were fixed on my back, but surprisingly, she didn't say anything.

Haim his grandmother

Little Hadassah, that's what everyone in Beit-Mazmil called the beautiful building that stood at the back of the neighborhood.

It was different from anything built there.

The immigrants' housing was crowded, coated with gray and ugly plaster, while the small Hadassah was a different world: a large and spacious building built with rows upon rows of small red bricks, with a large parking lot in front of it.

Who in the neighborhood thought about a car then.

Only one car parked there.

Every day at 11 in the morning, the doctor, a student and a family nurse went to make home visits to patients.

A large garden is cultivated around the building, with squares and squares of fresh grass and beds of roses and fragrant flowers, arranged and trimmed by the hand of a master gardener.

Who even saw a neat garden in the neighborhood then?

The children played in the field and in the streets, we only saw flowers in the valley when we went with the guides of the "Tikwanu" club to pick anemones and hollyhocks.

So they didn't know yet that it was forbidden.

Outside the neighborhood we walked almost to the red house next to the railroad tracks.

The guides warned us that the border was close there.

I will be seen.

I didn't understand at the time which border, and with which country, but as we got closer I saw that the guides were watching us with tense faces, like when we went for a walk with them in the Mosrara neighborhood.

On the first floor of the small Hadassah there were rooms for doctors and nurses, and a polished pharmacy, full of shelves and white cabinets and emitting a pungent smell of medicines.

On one white cabinet was a drawing of a skull, and in red letters it said: danger.

I didn't know what a menacing skull was doing in Hadassah's pharmacy, and what the danger was.

A laboratory was also there, and on its door was a large circle of yellow copper engraved with a large Star of David, and inside it was written in gold letters: "Long live my people, the charity of the Hadassah women in America for the new immigrants in the Land of Israel."

Two spacious halls were built on the lower floor of the small Hadassah.

One was a children's library, full of books about fives and caches.

A strict and bespectacled librarian always recommended thick books by great authors, but to her heart's content, the few children who came to the library actually took Kofiko's prank stories, the cover of which was already torn.

Sometimes they ask the stories of the young athletes who always beat the Egyptian soccer team at the last minute 12:13, after the Egyptians lead the whole game 0:12, after they kidnapped Israel's talented central striker with threats, or something like that.

At the last moment he landed by helicopter on the field, after the patrol released him.

The librarian was able to push with these books also a book or two by great authors that she wanted to be read, such as "Little Women" and much more.

When I once returned to her and told her that I read with teary eyes, she beamed.

Another conqueror for the world of literature.

Maya Arad

For 30 years I have been looking for the book "Yuala Magido", by Ora Shem Or.

I read it at least ten times, all before the summer of 1982. How do I know?

Because then we left Nahal Oz, and the only copy of the book I ever came across was in the children's library of the kibbutz.

In California, where I live today, children's libraries are spacious halls bathed in light with comfortable couches to stretch out on and librarians holding story time.

The children's library of the kibbutz was a small, narrow and cramped room (without a window, if I remember correctly), with crowded shelves and not always systematically arranged.

The usual suspects were there, Kofiko and Hasamba, Galila Ron-Feder and Deborah Omer, classics from Keter and the Marganit library. But there were also all kinds of books that came to be there in different and unusual ways, turning the tiny library into a wild, eclectic and diverse collection, such as "Yuala Megido" .

Today this book would be classified under "adult youth", but at the age of 10-11 it was a real revelation for me: this is the first time I encountered such a creature, not a children's book, but not a boring adult book either.

It's hard for me to remember the plot from a distance of more than 40 years, but I remember very well the sharp and ironic look of the girl Yoela on the world and the hypocrisy of the adults around her, especially her mother, who today they would probably call "poisonous", but then she was just a witch.

For years I searched for this book, in vain.

It came out in 1958 in an edition that was collected to its ancestors, and cannot be obtained.

If anyone has a copy, please call.

I would be so happy.

She stayed in Leo

Those were the days of the Corona virus, and the writer's meetings in the public libraries were held in small and fragmented groups.

And so I arrived at the library in the north of the country, and there the interviewer was waiting for me and we both prepared for the exhausting challenge: to have the exact same conversation twice in a row (for me, a conversation in front of an audience is a live, surprising, one-time event, and the thought of having the same conversation twice depressed me).

The first conversation went as planned, but I got carried away and didn't have the energy for the second conversation.

So does the interviewer.

We looked at each other with sad faces.

We had no idea how we would manage the conversation again.

The interviewer tiredly arranged her pages, and began to repeat the usual list of questions, "Your unique name is because... you wrote your book following... how did you start writing..." I saw her swallow a yawn.

Then inspiration struck me!

I asked the audience "can we try something else here?"

Everyone nodded, and I began to answer the interviewer's questions with imaginative inventions.

I invented where I was born, where I grew up, why I wrote the book.

I felt that a new character was being created, which one day will become a character in one of my books.

In the real world it was considered as if I had told the audience dozens of lies, but in the protected and highly imaginative space of the library, magic took place, the differences between reality and imagination became more and more blurred.

I remember not wanting the evening to end.

I wanted to continue being the same character, with an invented biography and a different life.

The audience understood, and the questions after the talk were also directed to the same other character.

There was magic in the air.

A magic that exists only in the world of spells and letters of public libraries.

., Photo: Illustration: Ruth Goili

Black honeysuckle

I grew up in the library.

It seems like an exaggeration but it's the real truth, because there I bit the side of the mushroom that raised me up.

As a child, the library was my safe place, and the librarians were my heroes.

Basically, it hasn't changed until today.

At least once a week I come to the Bat Zion library to exchange books and meet the librarians.

But I want to tell about my first librarian, who only recently, following a meeting with her granddaughter, the actress Adi Drori, realized that she had grasped the end of the thread that I thought had been dropped.

When Adi talked about her grandmother, Betty Drori, the librarian at Kibbutz Geash, she switched to an Argentinian accent.

It was only at that moment that I realized she had an accent.

In my childhood in Gesch, so many had a South American accent, but other things set her apart.

I arrived at the kibbutz from the city, and the difference flashed around me.

Betty the librarian let me take books beyond my age, but also according to my age, and never limited the number of books I borrowed.

She saw me, a little lonely girl who spoke as if she had swallowed an old translation, and listened to my passionate speeches about everything I had read.

A library is a place that contains a community of misfits, those who hold waking conversations with the dead.

Betty, I see, managed to love me.

I loved her with a passion reserved for children whose adults speak their language.

Even in Afek, the kibbutz we moved to, the library was dear to me.

There were also librarians there who let me be who I am, to discover who I can be through books.

When I was a student, every summer I returned to the kibbutz to work for my studies.

In a gesture of kindness, they let me work in the kibbutz's tramway (easy and sweet work, sponsored by the charming electrician), and in the library.

While on the tram I answered a few phone calls and spent whole days reading, in the library I cleaned shelves, wrapped books, sorted and arranged.

I am a witness that the electricity flowed there and there.

Galit Dahan Karlibach

In the neighborhood where I lived there was a serial harasser.

He was usually called "the pervert".

The word pedophile was not common on our tongues yet.

Usually the pervert would hang out near the playground and the schools, but one day, as I was entering the regional library, a particularly angry father burst into the community center - one of those rich local politicians who gained fame because of some marginal by-laws they managed to pass in the municipality. The father was accompanied by a policeman, who looked As if he had been taken from a particularly hearty afternoon nap, and that he was never going to forgive that.

"I demand to find the bastard," shouted the father.

The librarian silenced him indifferently, "Quiet, it's a library here."

The father and the policeman began to search the entire community center, and even disturbed the knitting class. Many knitting needles then got tangled in the threads. I ignored all the mess, entered the library and went straight to my favorite place: the shelf of globes and atlases. I opened the maps of Iceland and Norway, and with a longing finger I moved myself through all The ice lakes and fjords that were there. While diving into ice baths - I felt that something wrong was happening in the space. I looked across the entire floor. I noticed someone sitting there. In a moment I went out and returned with the father and the unfortunate policeman. The girl recognized the troublemaker.

"But how did you know?"

the father asked me.

I immediately rose to the rank of Edgar Allan Poe and said, "Because the book he read was upside down."

The father was so impressed that he decided to give me a free appointment for a whole year, and it was a very successful year in which I didn't have to steal books - and all this only because one fool didn't pay attention to a very important detail in the plot.

Tehila Hakimi

In the mid-1980s, in Gani Tikva, near the "Ravivim" school, there was the library. If you left the school gate and walked a few steps, you reached it, to its quiet space. The library was small, but it had the world, the secrets, and the books, the books." The "forbidden" of the great ones, distant districts, and of course there were also the librarians.

The library was the endless time, the silence of after school, of after school, the hum of the classroom, the teacher's voice and the noises of recess.

And although I grew up in a book-loving home, the library in our home was nevertheless finite - I knew the names of the books and their arrangement on the shelf by heart - while the public library was an endless space that renews, updates and expands - a world of new books, long shelves, floor upon floor.

There were the Hasamba and Gingi series, and books from the world: "The Secret Seven", "Around the World in 80 Days", and then "Little Women", and then the discovery of Agatha Christie, one of my favorite authors to this day. And if it weren't for the library , I probably would not have been carried away by the plots of Mrs. Marple and Hercule Poirot.

And the labyrinthine space of the library, in the meantime, also became, in addition to being a space of discovery - a space of fear, from the librarian. I mainly remember N.: a research librarian, who managed the The neighborhood information traffic from the public library and knew everything about everyone.

And once, under the influence of the crimes and murders at Christie's, I hid a coveted book in a place where it was forbidden to take it out of the library, I don't even remember what book it was, but I wanted it to be mine only.

The first crime, and to this day I have not been caught.

To this day, every entry to the library - for me there is an excitement that involves fear, when will I have time to read all these treasures?

A whole world that is expanding every day.

Illustration: Ruth Goili, photo: .

A sparrow from me

The house where I grew up had many books - but there were no detective books.

The first detective novel I read - "The Dog of Benny Baskerville" - I found in the old municipal library in Holon, one of the mornings where I spent long hours there, in searches whose purpose I did not yet know.

A few weeks later, after I devoured all the Holmes stories I found there and urgently looked for more detectives, the librarian introduced me to Agatha Christie's novels - and introduced me to Miss Marple and Hercule Poirot for the first time.

Of all the public spaces that the state provides for the welfare of its citizens or at their service - from schools, through hospitals to cemeteries - the public library is one of the only spaces that is a site of freedom.

Freedom to wander, freedom to be curious, freedom to choose and love books that are not in your parents' house.

True, the library is also a site of "education", but it is a special kind of education: there is no coercion in it.

You are invited to dive for hours between shelves with books of different colors, of different types, from other times (like diving between coral reefs, isn't it?) and choose from them yourself.

The library is also one of the last sites in our public space that is not dedicated to consumerism.

On the contrary - it subverts the desire to buy and the love of the new that we are all educated on.

A space of sharing, a space of exchange, a space where the new resides with the very old, where the glossy cover of the book that has not yet been read has no advantage over the soft, wrinkled-at-the-edges pages of the book that has been held by countless pairs of hands.

Without the freedom that the library gives us to wander and be curious and choose even what we don't have at home - we would all have much less freedom.

If the libraries can't continue to exist - if they can't continue to order new and old books, host story hours, hire professional librarians and librarians who know how to direct a girl to the book she needs - one of the most beneficial public spaces we have will be in danger.

Don't damage the libraries.

were we wrong

We will fix it!

If you found an error in the article, we would appreciate it if you shared it with us