Global society

all articles

On October 4, 2015, Judith Birkenfeld, then a woman of 44, uploaded a post to Facebook. It is a message to the people in their place in southern Denmark, to the neighbors. A post to introduce her son. She had just become a mother for the second time shortly before.

"We went through hell last week," she writes , "last Friday our little lovable star Daniel was born. He was born with Down syndrome."

And then : "We don't want you to avoid Daniel. You're afraid to speak to us. Please come over to us. Take a step towards us. Say hello to our sweetheart when you see us."

Birkenfeld says when she tells four years later that she felt she had to justify herself for Daniel. Because Daniel was the only one in town who has Down syndrome. Because her little son, who weighed 3750 grams at birth and was warm and crying on her chest, might not fit into the picture of a society in which people with disabilities are less and less able to live.

Maria Feck / DER SPIEGEL

Dad took time off: Daniel and his father Jesper Sørensen go for a walk

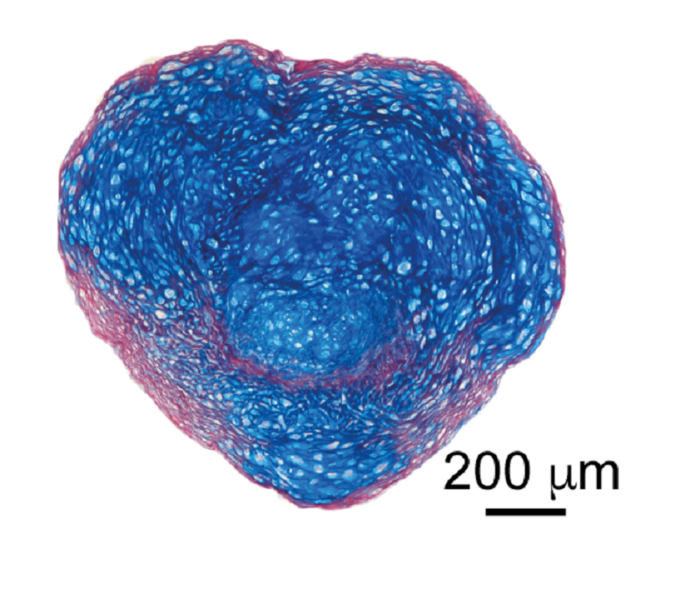

There has been a test in Denmark since 2004 that often prevents the birth of people like Daniel. Every pregnant woman can have her examined there free of charge within the first three months. The unborn child's neck fold is measured using ultrasound and the mother's blood is tested. Doctors use this, along with other factors such as the age of the mother, to calculate a probability of the child having a trisomy 21.

In Germany, too, a special blood test should soon be paid for at risk by pregnant women, which provides information about whether the unborn child has mutations in the genome, i.e. chromosomes too much, as in Down syndrome.

Screening has long become part of preventive care in Denmark, a standard that 97 percent of pregnant women perceive there. First of all, this means that 97 percent of pregnant women in the country can make a free decision about whether or not they want a disabled child.

But it also means a drastic consequence: Most children who are diagnosed with Down Syndrome in the womb are not born. 95 percent of these parents abort:

Denmark, as the "Copenhagen Post" wrote in 2011, "could soon become a society without a single citizen with Down syndrome". A few years ago, a documentary on Danish television entitled "Death of the Downs" showed that the number of Down syndrome births was close to zero - in fact, in 2017 there were only 13 children who were diagnosed before birth. In the film, parents report how they felt urged by doctors to have an abortion.

Birkenfeld also took the test. She knew that when she was pregnant, like in her case, over 40, the likelihood of trisomy was increased. However, her test was unremarkable and the pregnancy went without complications.

When labor started, Birkenfeld drove to the hospital with the idea of giving birth to a healthy son. "If we had known beforehand that our son would have Down's syndrome, he wouldn't be here today," she says. "We would have had an abortion too."

Maria Feck / DER SPIEGEL

Judith Birkenfeld at her dining table: "Does my child have Down? Is it broken?"

The paradox is that while people with Down syndrome are rarely born in Denmark, their starting conditions have never been as good as they are today: The welfare state of Denmark finances inclusion schools and kindergartens, special educators and grants, and good health care. Heart defects, for example, can be discovered and treated early.

People with Down syndrome usually live longer and healthier than before, many can work and lead an independent life when they grow up.

At the same time, the debate in Denmark is always about money, how much society saves if all women take the test and abort if the worst comes to the worst. Scientists call this "cost effectiveness", cost efficiency.

And what if a child with Down syndrome is born? How does a family with a disabled child live in a society that no longer wants these children?

Maria Feck / DER SPIEGEL

Two halves of bread with Nutella - Daniel's favorite breakfast before going to kindergarten

It's a foggy October morning in a small Danish town, an hour's drive from the German border. In the living room, it makes "Bing" and "Doing", quite loud, because little Daniel is pushing his gaming computer. Next to it is his breakfast on a plate: two halves of bread roll with Nutella. We are about to go to kindergarten.

Judith Birkenfeld tugs on the sleeve of her shirt, watches her son. Her husband sits down. Only shortly after birth did she realize that something was different with her child, she says.

She hadn't been able to take her eyes off the little fold that ran across the palm of her son's hand like a cord. Birkenfeld knew that this fold could be a first indication of trisomy 21. She asked the midwives: "Has my child Down? Is it broken?"

Maria Feck / DER SPIEGEL

With the wheel through the garden: "Daniel has completely changed our lives," say his parents

The parents remember the nights until the diagnosis was clear, during which they waited to know the result of the blood test. They remember how after a week a very nice and very young doctor said yes, it was trisomy 21. How they asked themselves questions that they had never prepared for:

Can we love a child with Down syndrome? How does our life go on with a disabled child? Parents in shock. Feelings to zero. Judith Birkenfeld says: "It was instilled into me that the Down syndrome is something very bad."

Maria Feck / DER SPIEGEL

Grete Fält-Hansen with her son Karl-Emil. She advises parents whose children have Down's syndrome

Grete Fält-Hansen is chair of the Danish Down Syndrome Association, an association that cooperates with Danish hospitals and advises parents of disabled children. She lives near Copenhagen and has four children, one of them with Down's syndrome. Karl-Emil is 17 years old and was born when the free screenings did not yet exist.

At the University of Aarhus, Fält-Hansen investigated how people talk about down syndrome in Denmark. She analyzed the choice of words in the information brochures given to pregnant women in Denmark. And found that the risk of having a child with trisomy 21 is mostly talked about instead of using the more neutral word "opportunity".

She encourages doctors to talk more sensitively about the subject when advising pregnant women. Instead of women with the sentence Do you want to exclude any risk? You could also ask: What do you want to know about your child? "If you are pregnant, you want to take everything, just no risk," says Fält-Hansen.

Maria Feck / DER SPIEGEL

Handshake with the neighbor: Daniel was integrated into the place immediately, says mother Judith Birkenfeld

When Judith Birkenfeld was still in the maternity ward, a nurse came into the room. The mother recalls that she called Daniel a "Mongolian child". That's when she felt this fighting spirit for the first time: Nobody should look at her son wrong.

It was this fighting spirit with which Birkenfeld then wrote the post on Facebook, the news of returning home with a disabled child. People responded with 101 likes and 83 comments, including only hearts and congratulations.

Birkenfeld says that her fears from back then were not confirmed in retrospect. Daniel was accepted immediately, she says. Many came to play with him, to hold him in his arms.

photo gallery

13 pictures

Photo gallery: "I was told that Down syndrome is something really bad""I don't know what people say behind our backs," she says, and: "I think a lot of people say about us: it's good that we're not in their skin." Birkenfeld also heard this sentence: "Couldn't you have known that beforehand?"

At the moment, she says, she does not have the feeling that Danish society per se is against people with disabilities. At least as soon as the child is born.

As if after the birth, the selection that prevails during pregnancy becomes an inclusion. As if the answer to the question of who is allowed to live was different once a child was born.

Maria Feck / DER SPIEGEL

Exceptionally, the mom took over the taxi service to kindergarten. Otherwise Daniel is brought by a driver

Shortly before ten. Daniel hops out of the car, the hood of his black hoodie hops with him. Today his mother drove him to kindergarten. Usually a driver will pick you up at home. Børnehuset Sønderskov, a flat brick building, is a special facility for children who are developing slowly. There is a physiotherapist and a bed for each child here. Here Daniel learned to express himself with hand signals.

The facility is financed by the state, as are the special schools and living groups that Daniel can later use. The state also finances the support programs, the care allowance, the social worker, who sometimes relieves the parents for a few hours. Judith Birkenfeld says that despite everything, you have to fight constantly for this support and negotiate with the municipality, it makes you tired.

Maria Feck / DER SPIEGEL

Welcome ritual in kindergarten: The educators are trained in dealing with Down syndrome children like Daniel

Sometimes she worries about how it will go if things go on like this. When people with Down syndrome are seen less and less in everyday life. Then do the fear of contact grow? The rejection? The lack of understanding? She fears that in the future it may become more difficult to network with other families who have a child with Down syndrome.

Living with Daniel often means laughing more than before because Daniel is constantly discovering funny things. A life with Daniel also means that he has completely turned his parents' life around, that he sets the rhythm. That he was still in diapers when he was four. That he can't speak yet. That Judith Birkenfeld is already thinking about where Daniel will be buried and who will pay for it when she and her husband are no longer living.

Maria Feck / DER SPIEGEL

Copenhagen: Most women in Denmark are diagnosed with Down Syndrome

Birkenfeld wishes women to be better prepared for what the test may tell them about their unborn child. That expectant mothers can make informed decisions for - or against - a child with trisomy 21.

This decision, Grete Fält-Hansen and Judith Birkenfeld agree, should always be one for which women do not have to justify themselves.

It should not be the same as it was when Grete Fält-Hansen carried two-year-old Karl-Emil in her arms in the supermarket. When you could already see that she was pregnant again. And when they met a friend who first pointed to Karl-Emil, then to Fält-Hansen's stomach and said: "But hopefully this time you had yourself tested before, right?"