The Venezuelan elites who, in the first decade of the twentieth century, joined the dictator Juan Vicente Gómez suddenly had to deal with the discovery of oil in our subsoil armed with very few ideas about the novel specificity of the oil business and everything that He made him no less than the foundation of a civilization.

That elite of "generals and lawyers with general ideas", as described by a European ambassador of the time, had already failed completely in his efforts of more than eighty years to establish a passably liberal republic that "growing out" was inserted into the World coffee trade. In 1903 the country, which boasted the best coffee in the world, was in absolute bankruptcy and European creditor nations imposed a naval blockade.

An expert phytobiologist, the Swiss engineer and geographer Henri Pittier, who had become a successful coffee planter in Costa Rica, was brought to the country in 1913 to evaluate our coffee trees and help relaunch them.

He found that, on average, each of our shrubs produced a crop of just 200 grams while one Colombian, Brazilian or Costa Rican was able to give two and a half kilos of cherries. He said that the deplorable state of the Venezuelan coffee plantation could only be due to much more than half a century of misery and abandonment that he rightly attributed to our civil wars.

MORE INFORMATION

Militiamen- Caparrós's question

- Venezuela: anonymous optimists?

Suddenly, the masters of the coffee plantation were faced with a problem that overflowed their capacities: to build a cognitive model of what the discovery of vast hydrocarbon deposits under their feet meant. Predictably, they assimilated the idea of "oil wealth" to the most familiar and approachable of "mining wealth," two subtle and crucially different things.

In a little read chapter of The Wealth of Nations , Adam Smith is the first to call attention to the specific difference that makes mineral wealth a kind of wealth in itself.

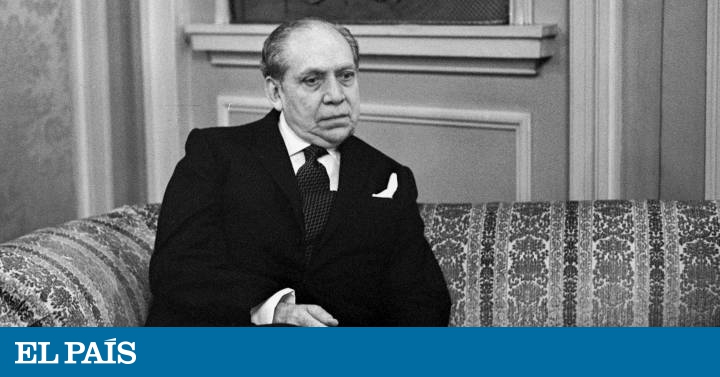

An enlightened offshoot of those Venezuelan elites was Arturo Uslar Pietri. The Venezuelans have treated him with poetic justice: they did not become president of the republic, in 1963, the conservative who in the 40s resisted with boldness that the Venezuelan majorities accessed the universal, direct and secret vote, but more than compensated him by incorporating Forever to his economic imagination the phrase that sums up Uslar Pietri's program: "sow oil."

That phrase is already part of the few intellectual belongings with which Venezuela has faced its material life for more than a century. Remember another, also of agricultural correlate, which was heard in Peru in the second half of the nineteenth century: "lay guano railways." The phrase "sow oil" condenses the representations that the Venezuelan makes of economic life, of himself, of his fate as a nation and even of his moral fortune.

When, in 2006, the centenary of the birth of Uslar Pietri was commemorated, in the local written press there were effusions about the “intellectual orphanhood” in which he left us at death, and there were even those who spoke of the need to “sow uslars”. They all hurt, Chavistas and Democrats, that the author of The Red Spears had failed to make himself heard by his countrymen.

But, if you look at things well, the paradox shines that the Venezuelan populism - of which Chavism was the last stop - did nothing during the second half of the twentieth century to anything other than the advice of its arch-investor. We already know the disastrous results.

Actually, I think there is not much to reproach men who in the first decade of the twentieth century granted the first exploration concessions: at that time and almost everywhere, of any wealth coming from the subsoil - and that did not resemble a tuber - it was thought, without more, that it was "mining wealth."

The alarms that the news of the oil findings in a society like the 1908 Venezuelan could unleash conjured an imagery of the gold chimeras: undesirable exodus, corruption, floodplains, abandonment of the field, bourbon , underworld, poker, shootings and prostitutes

On a deeper level, that assimilation of the specific oil nature to the undifferentiated mining brought with it another idea that, for many decades, presided over Venezuelan thinking about oil: the idea that, like gold mines or Pearl pleasures, the oil was going to end inexorably and very soon. And that truth and civic virtue were in agriculture and not in a Royal Dutch Shell camp.

“It is already a common place, and on which we will not tire of insisting, that of the need to invigorate the root and permanent sources of national wealth. Oil is a source of income that will last only a little over the next decade . To forget it is to reveal myopia and unpredictability. ” This was written overwhelmingly, in February 1938 !, in the newspaper Now , Romulo Betancourt, called "father of Venezuelan democracy." The italics are mine.

It was still necessary Hugo Chávez, Nicolás Maduro, the colossal “socialist” civic-military kleptocracy and the collapse of prices caused by the struggle between Russians and Saudis to, 80 years later, put a date on the prediction of Don Romulo.

You can follow THE COUNTRY Opinion on Facebook, Twitter or subscribe here to the Newsletter.