In June the Nigerian army announced with hype that they had killed nine of the influencersmost important of Boko Haram. The fight against the use of social networks by extremist groups has reached the point of physical violence. The fight against digital propaganda has overwhelmed the virtual world. On the opposite side, Habu Kalet Tijjani, has survived various attacks, he is dedicated to counteracting the extremist discourse in the networks from Maiduguri, the capital of the state of Borno, which has often been considered the stronghold of the Nigerian armed group. The concern to dominate messages on the Internet is reproduced in other parts of the continent, in which the same battle is being fought in which it is determined whether networks become a tool for radical groups or an instrument for improving the coexistence.

MORE INFORMATION

- Coronavirus does not affect blacks and other dangerous hoaxes

- The digital and street mobilization never seen in Guinea

- The story (and complaints) of the 'champion of freedom of expression online' in Tanzania

The consultancy RAND has already prepared a study for the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), which analyzes the use that Al Shabab, Boko Haram and the Islamic State franchise that operated on the African continent made of social networks. . The approach of that report was already that of networks as "a double-edged sword for development security". Kate Cox, the head of this research, warns that “we should not look at the online activities of Boko Haram, ISIL and al-Shabaab in isolation: Internet access varies by country and region, and even in high areas. Using social media, family, friends, religious leaders, and broader affinity networks can also contribute to radicalization. ”

Cox points out, for example, that this complementarity of the digital and real world is evident “in the case of Sudan, where the radicalization of students has been related to both recruitment formulas through social networks and interactions with a magnet inspired by ISIL on campus itself ”. In this way, the consultant's study indicated that the three main extremist groups operating in Africa at that time, did not have their key radicalization mechanism on social networks, but did use digital tools within a broader strategy.

In this context, Kate Cox specified the role of these channels: “Social networks can be a facilitator of radicalization, since terrorist groups can use online platforms to attract recruits, strengthen ties with their affiliates, coordinate or plan, claim attacks or criticize those who oppose its principles. "

For her part, Giselle López was one of the experts in the use of ICT for peacebuilding, who participated in an analysis of the messages broadcast by Boko Haram from Nigeria, promoted by the consulting firm Creative Associates International. "At first we thought that most of Boko Haram's communication would be taking place on dark channels such as Telegram, WhatsApp or private messages on Facebook and Twitter, but we were surprised that there was enough content to analyze on public channels, such as Facebook pages that were still working while we were doing the research. " López found three fundamental topics of conversation: religious references; discussions on the suspension and attack of accounts linked to the group; and global jihad and flirtations with the Islamic State.

The conclusions of this expert on the objective of Boko Haram on social networks are also illustrative. "We can say that online recruitment is relatively weak compared to offline recruitment," explains López, adding that "most of the content on public channels did not seek direct recruitment." The goals are different: “To attract attention, demonstrate your strength, connect with and impress potential recruits, support other groups you want to reach out to, and share messages that you believe will have an impact among your supporters. All of this helps recruitment, of course, even if it's not done through social media posts. ”

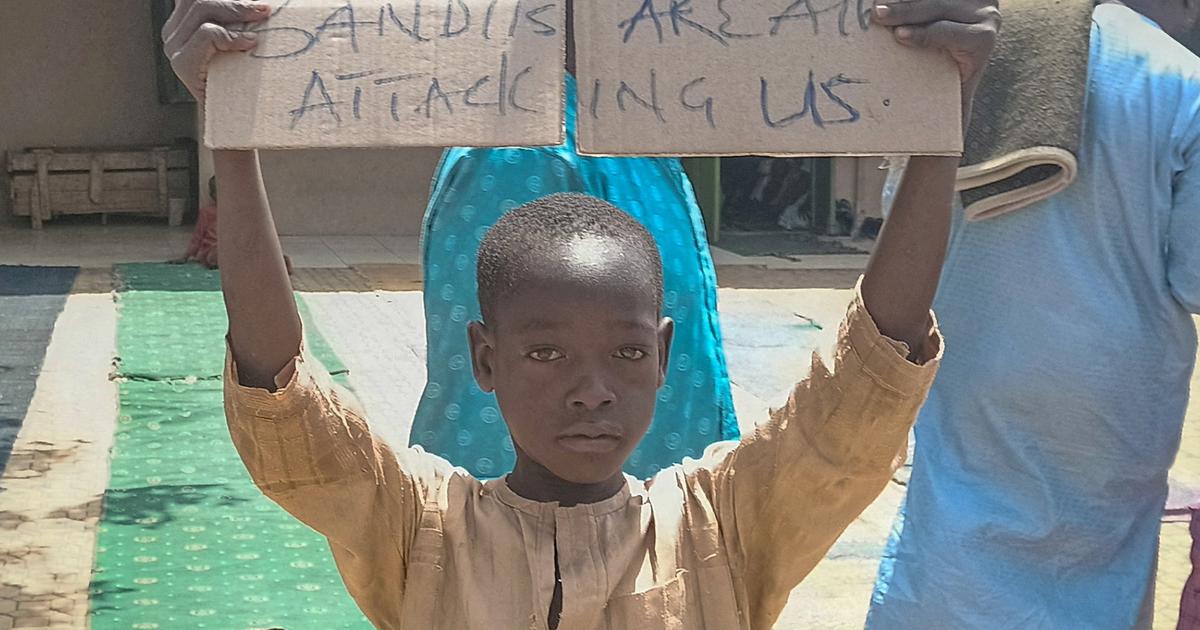

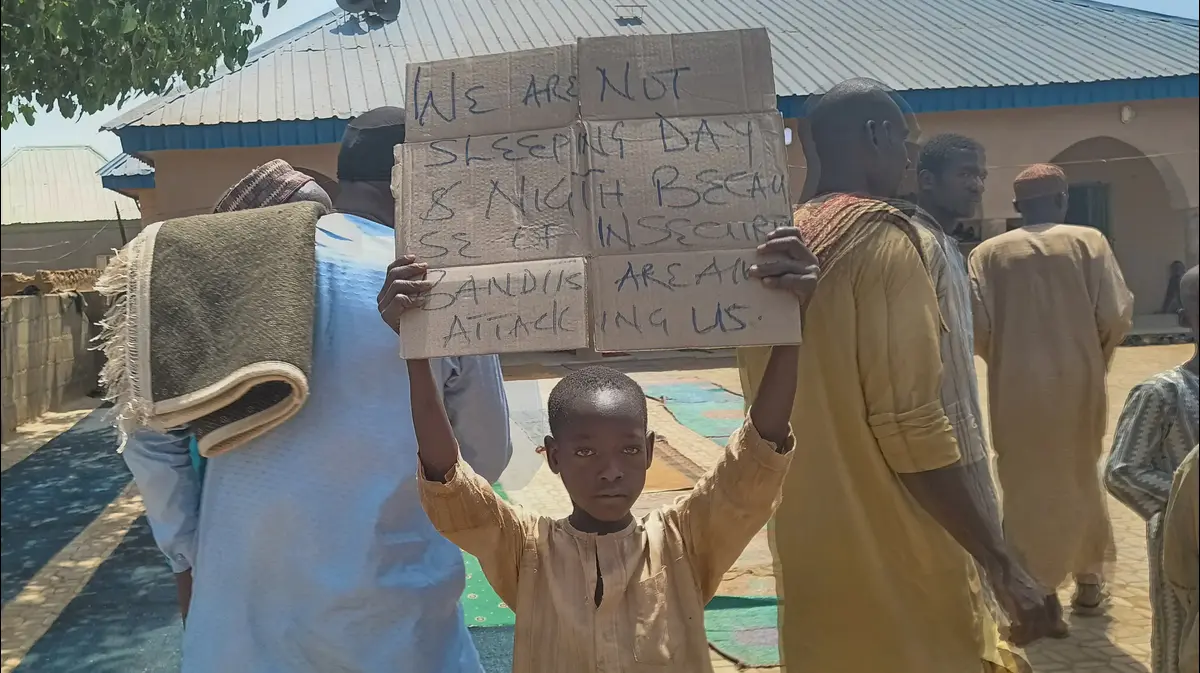

For López "it is often much more effective to direct alternative messages instead of counter messages" and in that logic of constructing a positive message is the Nigerian activist Habu Kalet Tijjani who alerts on a complicated context. “In 2018 I did a survey,” explains Tijjani, “and 9 out of 10 young people between the ages of 14 and 35 in Borno had a smartphone ; 8 out of 10 with a smartphone used social networks, especially Facebook and WhatsApp. Most worryingly, 83% of respondents watch negative videos about religious sermons and news related to violence before anything else. Young people are more at risk of being radicalized through social networks than by any other means. ” That is the context in which this activist has decided to combat extremist propaganda also using digital tools.

“I once posted a message about Boko Haram's activities and within 24 hours received responses, on social media, via phone calls, and even in person, and some young people started asking me for advice. Then came the survey I was commenting on before and the possibility of obtaining a scholarship from the US cooperation agency to counter violent extremism. Those have been my motivations ”, confesses this activist. Tijjani believes that this discourse built by extremist groups can be countered by using "short and attractive positive messages" and "using national languages and videos." For him, it is essential that this counterbalance to the risk of radicalization is based heavily on “local content” with which young people can easily identify and that “humanitarian intervention with awareness campaigns” are combined to also improve material conditions.

One researcher found several key topics of conversation: religious references, suspension and attack on group-linked accounts, and global jihad

Despite this evident threat, this Nigerian activist considers that the affected civil societies are not adequately exploiting the networks, because they still "consider that they are not significant" or directly "ignore the role they are playing", the importance they have in life daily life of these young people.

The two experts, both Cox and López seem to agree that a repressive perspective is not effective. In the EU environment, for example, Europol systematically removes extremist content, yet Kate Cox notes that “such actions can help temporarily disrupt terrorists' online activities, but censorship does not eliminate such activities and, as "Our report shows, it pushes them towards more private communication channels (for example, encrypted messaging services like Telegram or WhatsApp) and makes them more difficult to control." At this point, López agrees: “I don't think the answer to the negative impacts of social networks is to get rid of these platforms or block access. It is important that the companies that manage them pay attention to how their own platforms enable and exacerbate these issues and that they work with groups that understand the context and can effectively counter these trends, including violent extremism. These groups exist and often just need support. ”

For this expert, “social networks have had significant negative impacts worldwide, including the dissemination of hate speech, disinformation and violent extremism. However, they have also had powerful positive effects, such as favoring non-violent civil resistance movements, global solidarity or condemnations of extremism and oppression, and, in general, more open communication and access to information. ” "Actually," concludes López, "whether the effects of the networks are positive or negative depends more on the context, the medium itself, the speaker, the time frame and many other factors, not so much on the channel." And for this reason, she believes that it is important to support initiatives that have the capacity to spread constructive discourse, such as the #NotAnOtherNigerian initiative. One of these examples is the activity carried out by Habu Kalet Tijjani who acknowledges that he has received different attacks but avoids talking about them and who categorically answers the question of whether the risks are worth it: "Yes, I have always said so."

You can follow PLANETA FUTURO on Twitter and Facebook and Instagram, and subscribe here to our newsletter.