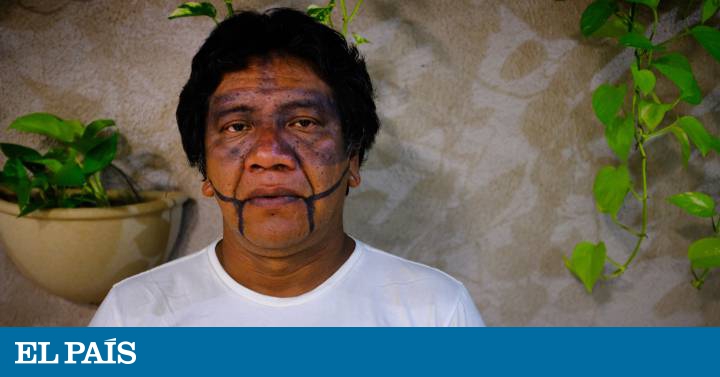

With his face painted in the traditional ways of his people, Dotô Takakire, one of the leaders of the Kayapó ethnic group in the Baú and Mekragnoti reserves in the Brazilian Amazonian state of Pará, does not hesitate to instill emphaticity in his claims. “The Ferrogrão will only be built if the Kayapó are consulted and if Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization [on the rights of indigenous peoples] is complied with. If not, there will be a fight on our part, ”he says.

MORE INFORMATION

PHOTO GALLERY A railway project that confronts settlers and indigenous people- China's Amazon Crossroads 1/3 | The dream of the jungle train loaded with soy

- Authoritarianism has already been established in the Amazon (and the urban peripheries)

- Chief Raoni does not cry, he rebels, and Sting supports him

Like many indigenous activists and leaders, this small and determined man believes that the Indians of the Brazilian Amazon face a crucial battle for their survival as a result of the Jair Bolsonaro government's plans to promote mining and agribusiness in the largest jungle tropical planet. But the last of his concerns has its own name: the "grain train".

It is a railroad planned to export more soy and corn to the world through the Amazon River basin. Considered as “strategic” by the Bolsonaro Executive, who this year plans to tender the work and its exploitation under a concession, it is already one of the most controversial projects in the entire region due to the potential socio-environmental impacts. "They are going to deforest more to plant more soy," says Takakire.

The Ferrogrão route, planned almost as if it were a line parallel to the BR-163 highway, the only one that cuts from south to north Mato Grosso towards the Amazon basin, does not cross either of the two Kayapó reserves, but it will pass very close. The main fear of Takakire and theirs is that what happened a few years ago with the construction - and later the asphalting - of BR-163, the route through which the production of agro-industry passes today, will be repeated. In other words, the Ferrogrão encourages, as the highway did in its time, the migration of more settlers and the pressure for land, which would lead to experts in deforestation and threats to indigenous peoples. For the Kayapó, there is no doubt that Ferrogrão threatens their reserves and, therefore, their way of life.

The Brazilian Minister of Infrastructure, Tarcísio Gomes de Freitas, does not share that vision. Like President Bolsonaro himself, Gomes de Freitas considers Ferrogrão a "revolutionary" plan for the country's agricultural industry, one of the engines of the national economy that, now, must take advantage of the tailwind created by the enormous demand for meat and legume from China. "It is a completely sustainable project that will lower the cost of freight," he explains. "We have immense potential to grow [in grain production], but the areas of production expansion are increasingly distant from the infrastructure currently installed."

Brazil is the great beneficiary of the trade war between Washington and Beijing, which has penalized US soybean producers. The political pulse between the two countries has caused the Chinese - who must import the grain to feed their immense herds - have replaced a large part of the purchases of American soybeans by Brazilians. In 2019, those sales totaled more than $ 25 billion.

Brazil is the great beneficiary of the trade war between Washington and Beijing, which has penalized US soybean producers

The South American giant has become in a few years the world's largest producer and exporter of soybeans. The great obstacle to exporting all that production is how to take it to the ports, since the country depends on road transport, which is more expensive and polluting. "The railway emits approximately a third [of CO2] from road transport," says the minister.

It is not the first time that Brazil intends to erect a freight train cutting the jungle to export raw materials. In 1982, still under the dictatorial regime of the military, the country built 892 kilometers of railroad between the Amazonian states of Pará and Marañao to link the Carajás region, one of the richest in the world in iron ore, with the port Atlantic of Punta Madera.

More than three decades later, the results of the Carajás train could not be more ambivalent: on the one hand, the 35 trains that run simultaneously on the railway line - each 330 carriages and 3.3 kilometers long - suppose a crucial infrastructure for Brazil exports millions of tons of iron ore to the world and enters valuable currencies for its economy; on the other, the outrages of people and livestock, as well as its controversial route, which crosses dozens of towns and divides them literally into two, is a constant focus of controversy.

Novo Progresso, the battlefield

The city of Novo Progresso, where the construction of a Ferrogrão station is being studied, is located on the agricultural frontier of Brazil. In this region, monumental jungle and monoculture areas adjoin. The city, a meeting point for the Kayapó with the settlers who arrived in the 1970s encouraged by the dictatorship, which promised "land without men for men without land", is more or less halfway along the route.

There is a constant tension between those who advocate "development" and those who advocate preserving the Amazon, a strategic resource in the fight against climate change. In fact, the police are investigating here the activities of groups of loggers and farmers who, emboldened by Bolsonaro's speech against indigenous people and ecology, have created a plan to set fire to jungle areas last summer, when the fires in the Amazon caused worldwide outrage.

The vice mayor, Gelson Luiz Dill, does receive in his office. The mayor, a controversial former gold digger accumulating processes in the Brazilian environmental entity (Ibama) for alleged illegal deforestation in nature reserves, has declined to grant the interview. To justify it, Dill criticizes the negative vision that the press gives of the city, usually described as typical of the "Wild West" by violent homicides linked, not infrequently, to the fight for resources.

60% of the economy of this municipality of 25,000 people depends, he says, "on the activity of more than 5,000 gold diggers" who operate in the fields scattered in the jungle. "But in 10 or 15 years," when the mines are depleted, the growth engine "will be agriculture," he says.

In Novo Progresso, part of the population believes that the Baú and Mekragnoti reserves - totaling almost 6.5 million hectares for a population of just 1,500 inhabitants - are an obstacle to present and future progress. Proof of this would be the opposition of the Kayapó to Ferrogrão. It is a speech (that of Indians hindering development) that has been unequivocally repeated by Bolsonaro and has been appropriated by politicians and the economic elite in this city that voted for him massively in the 2018 elections (78% of the total votes went to the ex-military).

"The Indian no longer wants to live in the jungle. He wants to live with society, "says Dill.

There is a constant tension between those who advocate "development" and those who advocate preserving the Amazon

Studies indicate that the Kayapó lands, as well as the dozens of reserves scattered throughout the Amazon and totaling a million square kilometers, are a green wall of containment for deforestation. They not only have the lowest destruction rates in the entire jungle. The indigenous people, with their active protection and vigilance of their traditional territories, have also been fundamental in revealing predatory schemes to appropriate public lands by devastating the jungle. In Novo Progresso, the Kayapó were the ones who raised the alarm a few years ago to dismantle what was one of the largest operations against environmental crime that sought to appropriate a public area the size of Manhattan.

But Bolsonaro's speech is also catching on among the Kayapó, who fear internal division in the face of threats. "Money talks; money buys, kills. Sometimes they also buy from indigenous people, ”admits Takakire.

In the Baú reserve, two villages want to break the tribal pact and allow gold mining, which uses mercury and pollutes the waterways where the Kayapó fish for food. An unflattering framework for Takakire, who sees Ferrogrão "as a very big concern." "Money can divide us and weaken indigenous leadership," he says.

Still, they don't give up. Since Bolsonaro came to power, the great chief Raoni Metuktire —also of the Kayapó ethnicity— has been one of the most active voices to denounce outside Brazil the threat to the Amazon. Takakire also wants to fight, but with actions. He promises to mount "a village in the area of the layout [of the Ferrogrão] if our rights are not respected." In the purest style of the movements of the Indignados or Occupy Wall Street.

About 500 kilometers south, on our next leg of the journey to understand China's impacts on the great rainforest, the Ferrogrão also raises concern. But not for its effects on the mainland, but for those that were and are the region's great highways: rivers.

To carry out this series of reports, journalists Heriberto Araújo and Melissa Chan traveled to the Brazilian Amazon thanks to a grant from the Pulitzer Center.

You can follow PLANETA FUTURO on Twitter and Facebook and Instagram, and subscribe here to our newsletter.

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/2C5HI6YHNFHDLJSBNWHOIAS2AE.jpeg)