Demonstrations condemning the Soviet regime's support for Arab terrorism against Israel were an impossible sight in the Soviet Union in the 1970s.

The demonstration in front of the Lebanese embassy in 1974

May 17, 1974 was another normal day for most Moscow residents. The USSR at the time seemed to be at its peak and was perceived by most observers at home and abroad as firm and monolithic. And he will do it in public, he will be bitter, everyone knew that.

Therefore, the spectacle that unfolded in the afternoon of that day in front of passers-by in central Moscow, near the Lebanese embassy building, was so imaginative that it could be likened to an alien invasion. Dozens of people, who appeared to be ordinary Soviet citizens, gathered near the mission of a Far Eastern country to protest and demonstrate. Processions, demonstrations and rallies were not entirely foreign to the Soviet landscape, but were always conducted at the behest of the authorities and in their full organization, expressing the messages that the government lacked from its regular propaganda arsenal: "Not to imperialism and Zionism", and "Long live communism and brotherhood".

But these hollow slogans were completely absent from the expansion before the Lebanese embassy, and were replaced by several makeshift signs whose contents were completely different. "Shame on the killers," the inscription shouted at one of them at the embassy, testifying to about 1,000 witnesses that it was not a demonstration on their behalf. The picture was completed by hundreds of policemen, who were brought to the scene ahead of time and now surrounded the extension. After a brief discussion with the protesters, they began making arrests. Freedom of expression and the Soviet regime did not go together, especially when it was the freedom of expression of the Jews.

Even today, from a distance of 46 years and many political upheavals, it is impossible not to admire the 50 Jews who came to the Lebanese embassy at the time to protest against the massacres in Maalot, mourn the innocent victims and bravely demonstrate solidarity with the tyrannical regime in Israel. Can anyone imagine that the Jews of Iran would stand by the Hezbollah mission in Tehran and dare to protest an attack against Israel? And that is exactly what happened in Moscow, with one difference - the Soviet regime was much stronger and scarier than the ayatollahs' regime in Iran.

The heart went out to Israel

"The horrific attack in Maalot was carried out by the terrorist organization 'Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine' two days earlier, on May 15," recalled Natan Sharansky, then a young man of 26. "When we, Jewish underground activists in Moscow, learned the tragic consequences - more than "20 killed, most of them schoolchildren - my heart was torn. I remember being called by veteran aliyah Alexander Lunz, who was a Zionist teacher for me, and he came up with the idea of demonstrating in front of the Lebanese embassy, since the terrorists came from Lebanon. I immediately agreed."

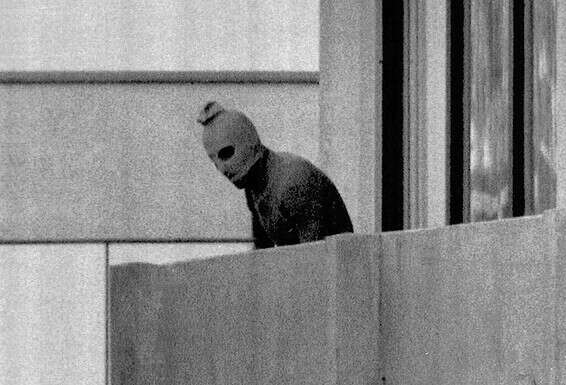

The massacre in Munich // Photo: EP

Sharansky joined Jewish activity in early 1973, and after an intense year of fighting the authorities was already a forged activist with a record of arrests. He and his friends were considered young activists who were not afraid of anything and did not wait for instructions from Israel. Because of the audacity that seemed more like recklessness, the older and settled-minded activists jokingly called them "Hong Wei Bing," a clear allusion to the zealous activists of the Cultural Revolution in China. Either way, Lunz's initiative fell on deaf ears.

"Everything was organized quickly and in an improvised way, especially in phone calls," says Sharansky. "I came to the Lebanese embassy after work. On the way, I called my wife Avital and told her about the plan, and so she managed to arrive towards the end of the demonstration, after taking a taxi.

"When I approached the place, there were already a lot of police in the area. Alexander Lunz opened the signs. 'Murderers,' 'We will not forgive you for the deaths of our children,' it read. We clearly blamed Lebanon, and with it we blamed the USSR, sponsor and patron The greatness of Arab terrorism. Police approached us and demanded to be dispersed without delay. I told them that we have the right to free expression. I liked to challenge them that way, although it was clear to everyone that the rights did not interest them. "

KGB warnings did not help

To the delight of the protesters, and to the chagrin of the deaf policemen who filled the area, not far from the Lebanese embassy stood the residence of foreign journalists. Unlike in democracies, the authorities in the USSR restricted the movement of foreign media representatives. Among other things, they were not allowed to choose a place of residence as they saw fit and were forced to live in some defined areas, such as the ghetto.

"These journalists arrived quickly, and perhaps thanks to their presence, the police let us stand with the signs for about 10-15 minutes," Sharansky adds. "It was surprising, because they would usually stop us immediately. After that, I started to specialize in contacting foreign journalists, developed code names with them and ran media campaigns that seemed to be taken from James Bond movies, but in May 1974 it was just a gift from heaven.

Sharansky. "We blamed Lebanon and with it the USSR" // Photo: Courtesy of the Genesis Prize Fund

"Although there may be another explanation. Perhaps the delay of the Soviet authorities was due to the fact that this demonstration was a surprise to them, because in all the other cases we prepared our demonstrations for a long time, and the news of the preparations was leaked."

The cops started pushing everyone onto police buses. The sequel was well known to Jewish underground activists. After each public protest, they would be brought to a place where their nature and even his name would not say much to those who did not grow up in the USSR - a special facility for holding drunks, where lovers of the bitter drop were placed until they became sober.

Also on May 17, the 27 protesters arrested were taken to "Facility No. 8." According to Sharansky, this was already a routine for him and his friends, so much so that "Facility No. 8" was considered a "Jewish facility": "We would be evacuated there after every operation, and I myself was detained there at least eight times. It was amusing to see how the police "Real drunks were thrown from there into the street, while they waited for a 'shipment' of Jewish activists."

The procedure at the facility included individual meetings with KGB personnel, who interrogated the detainees and asked them to warn against the recurrence of "Zionist behavior." This did not really help. Already that day, 100 people refused to immigrate from Moscow, 20 colleagues from Minsk and 7 others from Tbilisi signed a letter of protest. Against the heinous attack and sent it to the leader of the USSR Brezhnev and to the UN Secretary-General. Other Jews sent letters of condolence to the then President of the State of Israel Ephraim Katzir and the people of Israel.

Two days later, a group of Jews arrived in Kiev at the site of the extermination of the Jews in Babi Yar and asked to lay wreaths there in memory of the children murdered in Maalot. The Soviet police prevented this from happening. On May 23, 117 Moscow Jews sent an open letter to the USSR criticizing the Soviet media for the attack.

For some KGB members, the spectacle near the Lebanese embassy must have evoked memories of a similar incident that took place on September 6, 1972. On the same day, a group of Moscow Jews publicly identified themselves with the pain of the distant Jewish state. Israeli athletes at the Munich Olympics brought about 25 protesters to the embassy gates, including the famous dissident and human rights activist Andrei Sakharov.

Sakharov was not a Jew at all, but he knew how to distinguish between good and evil, between justice and injustice, and did not hesitate to act. In doing so, he supported the struggle of the Jews for freedom, and saw them as a worthy example to the rest of the people of the "Soviet prison." Also, Palestinian terrorism, largely nurtured by the USSR security forces and its metamorphoses, embodied in the eyes of the renowned physicist (father of the Soviet hydrogen bomb) and Nobel Peace Prize laureate the ultimate injustice, so it was clear that his place with the protesting Jews, despite the price Which will surely be charged from him.

Among the 25 protesters was the aliyah refuser Vlad Lerner, who remembers his feelings after the Munich massacre of athletes, as if it were yesterday: "The news of the attack created a deep shock. My friends and I felt it was a groundbreaking event, similar to the Six Day War, and simply could not help but express it. "It is no longer possible to recreate who first conceived the idea of how to express the protest, it was probably group thinking, but in the end we knew we would go out to protest against terrorism. A public demonstration!"

Jewish activists did not know how the authorities would react to such a public and defiant demonstration. "There was no precedent for our act, and in fact, both sides - the authorities on the one hand and we on the other - groped in the dark," Lerner explains. "To be sure, the informants and agents worked well: many of us were already detained on the way to the rally by the Lebanese mission. Some still managed to reach the embassy building. The place was already buzzing with police vehicles. We managed to open some signs and were immediately savagely attacked by police. They used very severe violence. "

Their little victory

Two years later, members of the Jewish underground learned from experience that they had brought foreign journalists to the scene, but in September 1972 foreign eyes were absent from the scene, and nothing prevented the police from striking the protesters and expressing undisguised anti-Semitic hatred.

"The policeman who caught me and led me to the vehicle was free from all inhibitions and completely open about what he thought of us. 'Too bad Hitler didn't finish the job with you,' he threw at me," Lerner recalled, and immediately finds the half-full glass: "We all stopped and were taken to the detention facility. Drunk, there I had the honor of meeting Sakharov, who was arrested with us. When we left, we left him our large family library. "

The pleasure of leaving the Soviet empire Lerner and his family (including his father, the renowned scientist Alexander Lerner, who stood with him at the Lebanese embassy) experienced only in 1988, after the outbreak of perestroika.

"They held us for 15-10 hours, and then we were thrown out into the street, but not before the KGB men had 'crowded' conversations with us. The questions were who organized the demonstration, the answers we used to give were 'I came alone'. "It is clear that this kind of action contradicted everything that the Soviet regime cultivated in its subjects - the culture of fear, the demand (especially from the Jews) to give up a national identity and become an obedient Soviet person," Lerner concludes.

Although in both 1972 and 1974 the authorities took care to silence the anti-terrorism demonstrations that hit Israel, the events in front of the Lebanese embassy in Moscow had results. Other Jews, who did not dare to join an open protest, or did not know about it at all, were exposed to the rumor of the brave Jewish act and joined the circles of forbidden Jewish activity, which included Hebrew studies, Jewish history classes and a decision to try to immigrate to Israel.

Although Arab terrorism has not stopped over the years, and other severe attacks have been carried out against Jewish and Israeli targets in Israel and abroad, protest scenes in Moscow have not returned. Sharansky has a surprising explanation for this: "The great event of 1976 was the hijacking of an Air France plane to Entebbe and the Israeli action to free the hostages. It shocked no less than previous acts of terrorism, only in the opposite direction: instead of great pain we felt immense pride and publicity.

"At the beginning of July 1976, we gathered in the apartment of the refusing to immigrate, Felix Kendall, and I spoke to those present about Operation Entebbe, after I leaked his details from foreign journalists. This is how I knew fascinating things that no one behind the Iron Curtain knew, like using a limousine, painting a soldier black That would resemble Idi Amin.

"When I told the story of the operation, the crowd refused to go upstairs could not stop their joy, and the cheers waved me in the air, as if I had released the hostages. However, that did not end the celebration. The atmosphere of admiration was so powerful that it slipped out - people left the apartment "And shouted 'Victory! Victory!', Passers-by looked at us in amazement, they did not know of any victory."