Tallandier

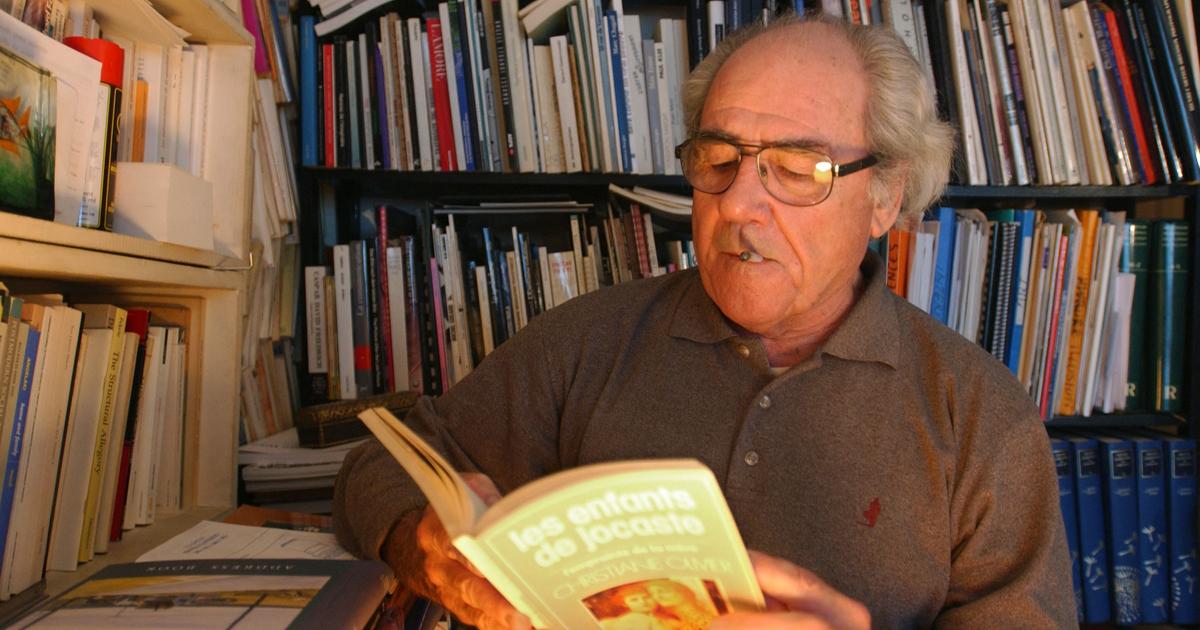

Pierre Vermeren, normalien and associate of history, professor of contemporary history at the University of Paris-1, is the author of numerous books hailed by critics. His new work, “We broke the Republic - 150 years of the history of the nation” (Tallandier, 320 p., € 19.90), has just been published.

FIGAROVOX.- Your book tells the foundations of “French-style republicanism”.

What is it exactly?

Pierre VERMEREN.-

Today's dominant discourse psychologizes and moralizes the Republic and citizenship.

However, in 1870, the founding fathers of the Republic established the imperative need to avenge the humiliation of France in the face of Germany, while affirming their desire to build a politically egalitarian republic, faithful to the great principles of 1789. To achieve these ends, they reformed the nation.

First, by unifying the French through their institutions: compulsory schooling, the conscription army, the municipal regime, and the law passed in Parliament.

Then by forging a national elite in accordance with articles 1 and 6 of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen: education for all, excellence for the best.

Faced with Germany, they mobilized the people through an intellectual fighting nationalism, and built an army as powerful as his (despite our relative demographic decline).

Finally, the Republic would exert all the necessary force in the face of its enemies, real or supposed, whether they are of the extreme left, monarchists, Catholics or foreigners.

We learn, by reading you, that, under the Third Republic, until 1905, “a teacher had the same salary (therefore the same administrative rank) as a captain, a professor, a colonel, and a professor of the universities than a general. "

It's surprising!

How to explain it?

The Republic is based on two armies (or even three until 1905, because the clergy was the third public "army").

The first is the army in the strict sense, the only hope of defeating Germany in order to recover Alsace-Lorraine, the objective of the war to come.

This requires forging a gigantic army of 3.8 million immediately mobilizable men, on par with the German Empire.

This citizen conscription army, with its three years of active military service from 1913 and its reservists, is supervised by officers of high scientific and intellectual level.

The 80,000 “black hussars” (Péguy) or schoolteachers, the nation's other elite, received high-level intellectual, political and moral training.

For the Republicans, there is no difference from this point of view with the second "army", Public Instruction.

The 80,000 “black hussars” (Péguy) or schoolteachers, the nation's other elite, received high-level intellectual, political and moral training.

As for high school and university teachers, in charge of 2% of baccalaureate holders of an age group in 1914, they cultivate the nation's elite.

What should surprise us today is the downfall that has struck these two "armies": the first is weakened by the reduction in its resources;

the second by the failing training and socio-economic downgrading of its members.

During the Belle Époque, dechristianization and secularization "did not make Catholicism regress as a normative system and frame of reference for the life of the French", you write.

Isn't that a paradox?

It is an apparent paradox of the 19th century, a great century for French Catholicism.

The proactive dechristianization carried out from 1793 to 1801 ended with the Concordat of Bonaparte (1801-1905).

Over the course of the 19th century, after 40% of its heritage was destroyed and its clergy wiped out, the Church rebuilt its positions.

Then it went from the reconstruction of the building to the reconquest of the people, the school, the elites and the country, and to a world missionary phase.

France had more priests and religious in 1880 than under Louis XVI.

And three quarters of Catholic missionaries around the world are French.

France had more priests and religious in 1880 than under Louis XVI.

And three quarters of Catholic missionaries in the world are French!

It is not only the colonial Republic which is universalist.

At the end of the 19th century, 95% of the French were baptized, and the Church educated more children than the Republic.

If, in Paris and among the workers, irreligion progresses, the power of the Church enraged the Republicans.

They are in the majority in the Chambers and the government - from which Catholics are excluded - and refuse the vote of women considered favorable to priests.

This pushes them to impose not a dechristianization - the balance of power forbids it - but a combat secularization, radical between 1902 and 1905. It is because the Church still influences society a lot that it must be expelled. of the republican state.

A big difference between yesterday and today, you can imagine, is that the well-to-do classes, which lived in daily contact with the people, did not secede.

Isn't this a surprising analysis given the enormous distance which then separated the well-off social classes and the popular classes?

This distance is identical today, or even has worsened culturally.

Above all, the well-to-do classes felt invested with the mission of educating the people.

Whether they are Catholics or Republicans, bourgeois, doctors or intellectuals, the heirs of the Enlightenment want to tear the people away from their ills (obscurantism, alcoholism, violence etc.), educate them (instill French in them), police them (disseminate the "Good manners"), to civilize it in the proper sense (whether he is bougnat, Breton or Kabyle).

Nothing like it these days.

The physical secession added to the social cut.

In the 19th century, countryside and small towns brought together all social classes: let us reread Proust or Maupassant.

The society was very unequal, but bourgeois and notables lived among the people.

They shared the economic activities, religion, language, leisure sometimes.

Nearly a million servants also lived with their masters.

In Paris and in the big cities, the social classes lived near or in the Haussmann building.

Social elites then represented 2 to 3% of the French.

30 to 35 million invisible French people have gone by the wayside: this is the big lesson of the Act I yellow vests.

Today, executives constitute one in five employees and more than a third of the self-employed.

The upper middle class, the bourgeoisie and their retirees, are 12 to 15 million French people, grouped together in communes or regions: the West of Paris, the metropolises, whose speculation and the economy have driven the popular classes towards peripheral France.

Recent immigration, in social and sometimes unsanitary housing, has replaced them there: these are the famous “working-class neighborhoods” mentioned by the press.

But 30 to 35 million invisible French people have gone by the wayside: this is the big lesson of the Act I yellow vests.

Let's move on to the Trente Glorieuses.

One of the features of the 1960s, you explain, is the “passage to the left” of a significant part of the clergy and the faithful.

How to explain it?

In the 19th century, the Church of France made two capital errors.

Horrified by the Terror, she rejected modernism and new ideologies, opting for weakened royalists: but the French gradually rallied the protective Republic.

The Church is then forced to accept modernism and rally the Republic, but embracing colonization.

The missionaries rendered a great service to the Republic without having wanted the Empire.

Then in the 20th century, the Church, which found all the French in Verdun, embraces for better or for worse the tragedies that swept the country from 1914 to 1962.

In the 1960s, the institutional Church and young Catholics shifted to the left.

For the baby boomers born in the 1940s and 1950s, who reached adulthood after the Algerian War and Vatican II (1962-1965), the Church must atone for past political faults, return to Christ, renounce the theology of sin, becoming invisible, modernist and social.

The inversion of values is total: works take precedence over faith, and other religions are a way of access to God.

The institutional Church and young Catholics are tilting to the left.

In 1968, two out of three bishops were “red”.

The Church has achieved what the Republic has been powerless to achieve: it has dissolved itself by losing its faithful.

Regarding the Fifth Republic, you judge that all our leaders have more or less adopted the same position favorable to immigration, in spite of nuances.

Can we synthesize the different factors that explain such continuity?

Let us make a distinction between European and Algerian immigration of lone workers during the Thirty Glorious Years, and Afro-Asian family immigration post-1979.

In the absence of in-depth parliamentary and democratic debate on immigration, and due to the unanimity of political elites, no one has measured the long-term consequences of this change.

In the absence of in-depth parliamentary and democratic debate on these issues, and because of the unanimity of the political elites - the PCF and the unions join the consensus under François Mitterrand - no one has measured the long-term consequences of this change. .

Why was this so?

The first reason is geopolitical: after 75 years of demographic stagnation (1870-1945) which led to the disaster of 1940, the French elites want to increase the population through family policy and immigration.

It's about catching up with Germany.

The second is economic: French employers have a constant need for new labor to weigh on wages, weaken revolutionary unionism, and expand the number of consumers: the lower the birth rate, the more it has to be imported.

The third is sociological: the French political and educational system promotes social advancement for all.

Despite the failures of this model, against the backdrop of the destruction of the productive economy since the 1970s, young French people - including those with an immigrant background - refuse the unskilled and poorly paid jobs of their parents: in the eyes of the elites of the countries, new docile immigrants are therefore needed

Let's talk about the present.

You are very harsh on decentralization.

Was it not inevitable, and even desirable, to do away with the supervision of the prefects over the mayors?

If decentralization has broken the Jacobin march that has been going on for centuries, it has not been the subject of great public debate.

It was imposed by parties and elected officials concerned about their careers and their power.

This turning point responded in its own way to the anti-authoritarian pressures of the 1970s. But in our Latin country, the new-found freedom of local executives (notably mayors) exposed them to business, various pressures and corruption.

As a result, in forty years, France has built and concreted the equivalent of 4 departments, ie 4 times more than during the previous millennium.

Never have the services of the State been as concrete as the mayors have done since decentralization.

The more France has deindustrialised and the more agriculture has lost its jobs, the more the major equipment, retail and urban planning sectors have grown.

The city dwellers and their activities were moved to immense suburbs, creating "ugly France" and metropolises, ruining the centers of small towns in the process.

We can measure the aesthetic, ecological, energy and social damage with the ensuing crises: suburbs, yellow vests and ecology.

The state services would never have installed this chaos.

You strongly criticize the revolving door of members of large state bodies who left, after a brief stint in the ministerial cabinet, to lead large companies, while remaining members of their original body.

But is it so new?

A century ago, there were already Financial Inspectors who went to the bank ...

There are several new features.

Until 1974, apart from the war, France did not get into debt: since then, indebtedness has been endless.

Financial inspectors were therefore not exposed to the risk of impoverishing the state for the benefit of their future or former banks.

In fact, everything is new in this area: the ease with which senior officials move from the service of the State to that of private interests, the back and forth and the porosity between these two worlds, the constitution of private fortunes to shelter of public status, the accumulation of pensions hats.

The financialization of the economy has pushed many senior officials to forget the national economy, production and industry.

The financialization of the economy has pushed many senior officials to forget the national economy, production and industry in favor of incessant financial combinations.

The result is a French economy that is indebted, deindustrialised and without growth, except that of debt.

Deputies and senators have identified the perverse effects of revolving doors for lack of a serious control body: but the Council of State has constantly rejected them.

Under the Third Republic, a law would have settled the question in six months.

You ridicule the consultants adept at globalization who, while considering settling in London or the United States, "lavish their advice at great expense to French administrations accused of inefficiency, heaviness and mismanagement."

So what?

Would drawing inspiration from private methods be blameworthy in principle?

Certainly not: the lack of human resources management at National Education proves it absurdly!

But the liberalization of public services desired by our leaders - who made it endorse to Europe - has led to ubiquitous situations.

Historians will unravel the web of responsibilities that led to the destruction of the great French-style public services that were functioning well and at reduced cost.

Of course, France Telecom, now Orange, has faced an exceptional technological revolution: but the tragedies which condemned its leaders were they not avoidable?

Why is La Poste struggling to distribute packages today?

Why, in ecological times, have we sacrificed sea freight, rail freight and canal maintenance?

Why is La Poste struggling to distribute packages today?

Why, in ecological times, have we sacrificed sea freight, rail freight and canal maintenance?

Why does the indebted SNCF manage so badly to make the suburban trains and RER work on time?

It's hard to believe that it took so many consultants, cost hunters, auditing and consulting firms to achieve these results.

In the name of the "inefficiency" of public services, we gave up covering the territory, employing people who have become on social assistance, and maintaining the regretted social link.

We have gone from "having a job" to "having a job", you deplore.

What is the difference?

That between qualified work, the nobility of the profession learned at length and of which one has become a master, and the interchangeable job, the disposable "job".

The "modernity" into which we have rushed for 40 years has been an immense undertaking of deskilling of manual and intellectual professions.

Hence the adage: "Everyone will have 4 or 5 jobs in their life".

It took years - even a life - to make a good plasterer or a cook: it now takes a few weeks.

It has consequences.

It took years - even a life - to make a good plasterer or a cook: it now takes a few weeks.

It has consequences.

The only French cooked dish will soon be the burger, and in the building, the calamitous water leaks after the inauguration of the Archives de France or the new Judicial City attest to the ravages of poor workmanship.

The intermittent companies and subcontractors send who they can.

The apotheosis is reached with uberization and bicycle portage: it is the return of modern slavery in the heart of globalized metropolises.

The "social and territorial partition" that France is experiencing "was by no means compulsory: countries like Japan or Germany have made different choices while preserving their industrial and productive model, and therefore its effects of social mix", judge -you.

To stick to Germany, how did our neighbors achieve this enviable result?

This is a formidable question, because 75 years after the war, Germany has taken a resounding revenge.

Our economy and the continent are in his hands: our nuisance power protects us, because if the euro zone breaks up, Germany also loses its feathers.

This is the reason why she accepts that our debts are aggravated.

Our elites built an institutional mechanism in the hope that France would rule Europe when the Germans modernized and forged their industry for globalization.

In the end, they rule Europe;

they have robots, and we have the unemployed.

Germany rivals China for export, and we have a trade deficit with Italy!

This tragedy has come a long way.

But we have a problem with the real.

The French were excellent soldiers and administrators, which once made it possible to conquer Europe or to build a colonial empire.

But today, in the ruthless liberal globalization, our talents seem useless.

Will the return of storms be good for us?

Perhaps.

But on the condition of recovering our productive and energy autonomy.