FOLLOW

Follow

Barbara K. Wheaton's (Philadelphia, 1931) first cookbook was

Irma Rombauer's

The Joy of Cooking

.

She bought it shortly after beginning her studies, spurred on by the human need to eat and the sudden discovery that she had no idea of cooking.

He had had his first culinary adventure the night before: he boiled some potatoes.

That copy was the first in a list as long as the universal history of gastronomy.

Medieval cookbooks, housewives' manuals, agricultural treatises, medical books and, in general, any work related to the task of producing, preparing and consuming food have passed through his hands.

And with those same hands he has built what is called to be the great culinary library of the internet.

The Sifter -the colander- is the result of the last fifty years of work of this North American historian: a growing database that registers authors, names of recipes, techniques, ingredients of more than 7,000 books and that is now available online for the consultation and contribution of anyone, in the purest Wikipedia style.

"It contains ingredients and methods, and things related to cookbooks. But food has its roots in science, agriculture, religion, film, television, magazines ... It is actually a database on the life, "says Wheaton, who has already turned 89, from the nursing home where he lives, now confined.

The historian, seated in front of a shelf full of books, carefully holds the microphone on which she is reeling off her life project.

The other faces on the video conference are those of two of his three children, Joe Wheaton and Catherine Saines, who have collaborated in the launch of the platform.

It all started when a young Wheaton entered Harvard to study Art History.

“I realized that cooking, like painting and all the arts, is shaped by the time and place in which it takes place.

It can be classified in the same way and in many ways it is more descriptive ”, explains the historian.

In the Harvard library he delved into reading the first editions of the first printed cookbooks and the manuscripts that preceded them.

But Wheaton's mind, while undoubtedly prodigious, was soon too small for so much information.

“I needed a system to structure the information and compare it.

And this was before personal computers ”, points out his son.

“There was a computer at Harvard that took up an entire building.

We used to go see him do mysterious things.

I never thought I would have one ”, recalls the researcher.

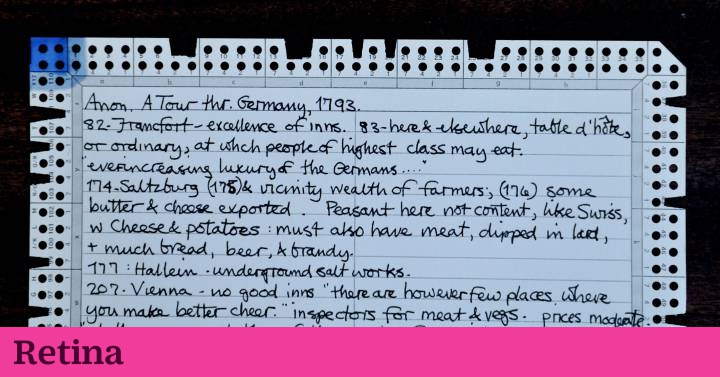

One of the punch cards used by Wheaton

As it is, the best option he found in the analog early seventies was to use McBee punch cards.

These sheets allowed him to categorize the information according to the different holes and later filter the contents of the different cards by traversing the set with a knitting needle.

The system was effective, but laborious: breaking down the contents of a new work in the database could cost up to a month of work.

After nearly a decade, this primal form of big data also became insufficient to manage the volume of categories, explains Wheaton, who tried to expand its capabilities by adding color coding, but again overwhelmed it.

Luckily, computing came to pass in 1982 in the form of an IBM PC.

It was not the first model, the initials would not even have worked: its keyboards devoid of accents and, in general, non-English characters, made it difficult to include entries in other languages.

“The people who were inventing them didn't know the languages that require them.

They were too young and too California, ”jokes Joe Wheaton.

The IBM XC personal computer, launched in 1983 Getty Images

"I decided to learn a little about computers because I felt that people were using them to boss me around," says the historian, who was confident that some notions of computer science would allow her to fight back.

With the new tool, the historian gained in efficiency both in the recording of new information and in the potential to contextualize and analyze an increasingly wide corpus of information.

In 1983 he published

Savoring the past

-

Savoring the past

- a book on French cuisine from 1300 to 1789, combining his analog and digital efforts from the previous ten years.

And, with a good command of the database manager Microsoft Access, he continued rummaging through old recipes and feeding what was then called

The Cook's Oracle

-

The Oracle of the cook

-.

"That was a simpler version of The Sifter, because database programs were simpler then."

For the past half century, Wheaton has stayed on the cutting edge of what was possible for the technologies that kept him moving forward.

The need to establish more relationships between items in the database and the simple fact that, once again, there was no more information in Access, it took her to the next level.

"Now I use a system that is complicated enough that I don't know what to do and have to ask my daughter for help," Wheaton continues.

In the oracle, information was presented as disjointed lists of books, authors, chapters, recipes.

In The Sifter the references are crossed so that you can search for a single term (everything to do with beans, or simmering, for example) in all categories.

"Mom says it's like a matryoshka, you can go from the widest to the most concrete or from the most concrete to the broadest," says the researcher's son.

Result of a generic search in The Sifter

If we look for "fire", we get techniques for toasting the surface of a plate or boiling spinach.

But we are also given tips for stopping flames on a woman's dress that has accidentally caught fire.

If we look for "bread" we find recipes that go from 1430 to 1845. With this strainer we can filter dishes as common as a boiled egg and as unusual as a "frog stew with saffron" or a "cake to provoke courage in men and women" .

The sand of the cold beaches of Maine is for Wheaton the perfect metaphor for the dimension of his life project.

"Once we were staying there with some friends and as I was lying on the wet sand on a cold rainy day, thinking about old cookbooks and looking at the grains of sand, I realized that these represented the problem with the I was facing. Those grains of sand of different textures and colors obviously tell the geological story of the Maine coast, "he recalls.

Similarly, the myriad details recorded in The Sifter tell something much deeper than the directions for preparing a particular dish.

It is enough to provide structure to the sandbar.

How has the role of the potato evolved through world history?

How did the type of recipes found in the cookbooks for housewives differ from those written by illustrious chefs?

Does the gender of the authors determine the value of the ingredients used?

Barbara Wheaton pictured in Paris in 2000 Getty Images

The Sifter has come to the Internet thanks to the tenacity of Wheaton and his family.

A year ago, they hired two programmers to make the final leap.

"I am getting the money from my children's inheritance," jokes the historian.

The next steps, explains his son, are to improve the usability of the platform, attract contributions from Internet users from around the world - they are in talks to incorporate 5,000 medieval recipes collected by researchers from the University of Graz (Austria) -, establish intelligence systems. capable of extracting information in an automated way and providing the platform with options that allow the data to be viewed.

"Mom is no longer a child, we wanted to finish it as soon as possible so that she could be involved, enjoy it, advise us," she explains.

Barbara Wheaton's only obsession is that everyone can freely access The Sifter.

"I want people to have fun with it. Who knows? Someone might learn something new and enjoy it. I think one of the great impediments to learning is that if people don't have fun they are less likely to learn."

You can follow EL PAÍS TECNOLOGÍA RETINA on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram or subscribe here to our Newsletter.