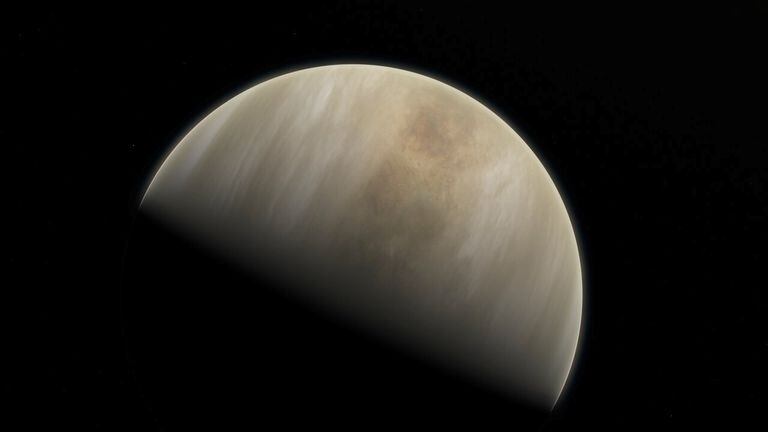

Representation of the atmosphere of Venus by the European Southern Observatory (ESO) ESO / NASA / Reuters

Shortly after news broke of the detection of a gas associated with life on Venus, a Dutch astronomer did what every scientist should do when an astonishing finding is published: try to reproduce it.

Was it true that in the atmosphere of Venus there is phosphine, a gas that on Earth is associated with microbes?

After doing a reanalysis of the original data, Ignas Snellen's team at the Leiden Observatory (Netherlands) is clear: it cannot be said that the gas is there.

"It is impossible to maintain the results of the original study," explains Snellen to this newspaper.

His team published the results of their study a few days ago, which is still preliminary, as it has not been evaluated by independent experts.

At the same time, the scientific team at the ALMA radio telescope in Chile, the most powerful of its kind and whose observations were fundamental in the detection of phosphine, has begun a re-analysis of the data, which may have been invalidated by a calibration error of his tools for analyzing the light coming from Venus.

This telescope is part of the European Southern Observatory, made up of 16 European countries, including Spain, and which announced the original find with a press release entitled: "Detected a possible marker of life on Venus."

Already at that time many experts were skeptical that life was the most plausible explanation for the sign, if it was real.

ALMA officials do not want to say if the signal has disappeared or not until the authors of the original study reanalyze the data with the well-calibrated tools and check if the phosphine signal is still there.

Most of the experts consulted, including Snellen himself, see it as almost impossible.

"The detection of phosphine in the atmosphere of Venus does not hold up after our reanalysis of the data," concludes a team of nearly 30 astronomers from NASA, the University of Berkeley, and other institutions, in a second preliminary study that almost hacked deadly to the original study. Its makers have re-analyzed the original data using different computer tools and concluded that there was an incorrect parameter in the original study. Without that parameter, the phosphine observation vanishes.

The authors of this work sent their results to

Nature Astronomy

, the journal that published the original study on phosphine on Venus.

The journal contacted the team responsible for the study for an answer.

That answer may take "weeks", according to the people in charge of the ALMA telescope.

And until they are pronounced, there will not be a final verdict.

MIT astronomer Sara Seager and Jane Greaves of Cardiff University (UK), leaders of the original study, have declined to comment on the two studies that question their findings.

Greaves has acknowledged to this newspaper that they are waiting for ALMA to finish the calibration of its analysis tools to recheck if the phosphine signal is still there.

A big part of the problem is that all these astronomers face a devilish challenge: to detect a molecule with a concentration of millionths in the atmosphere of a hellish planet, very unknown and that is more than 100 million kilometers from Earth.

This represents a technological challenge that only instruments like ALMA, made up of 66 antennas installed in the middle of the Atacama Desert, can face.

And still it is possible to fall into a mistake.

It all begins with the naked image that is captured of Venus, the raw light that gives off its atmosphere and that is full of noise, confused signals that prevent us from knowing what is what.

To clarify this, astronomers use

software

tools

that have been tested in known environments and then apply to new environments, such as the atmosphere of Venus.

This planet suffers from a greenhouse effect so wild that its surface is 400 degrees.

In contrast, the upper layers of the atmosphere can have a temperature similar to that of Earth.

It is right there where the team detected a signal of phosphine, a gas that on our planet is associated with the presence of life: microbes.

The original

bare

signal

was extremely complex, full of lines that were mounted on top of each other like on maps representing mountain ranges.

The main problem with the original study is that the

ALMA

software

designed to analyze the raw image of Venus was poorly calibrated, as the NASA team's reanalysis shows.

The team has used two other alternative programs and with them the signal disappears.

But it is that even if there was a signal, they say, it could not be phosphine, but another compound that emits a very similar wave: the toxic sulfur dioxide that is ubiquitous on the planet.

In addition, there would be an inconsistency between the signal captured and the supposed height in the atmosphere at which it was detected: the phosphine should be more than 70 kilometers from the surface, but the team saw it at about 50.

Snellen's team further shows that the original study used a mathematical function to clean up the

noise

from the original Venus signal that was not adequate.

With the function, the phosphine signal is 15 times stronger than the surrounding noise - quite a breakthrough.

But using another more conventional and accepted function in astronomy, the phosphine signal is only twice as strong as the noise - so weak that the compound cannot be said to be there, Snellen explains.

The person responsible for this work believes that Greaves' team "made a mistake when analyzing the data, but they did not do it on purpose."

"I'm disappointed, but not surprised," explains Kevin Zahnle, a NASA scientist who acted as an independent expert in reviewing the original study.

"I was in favor of the publication of this work because I wanted to see if other teams confirmed or refuted it, which is what happened." The astronomer does not believe that the original study should be withdrawn. "If each case of self-deception like this If it were retracted, 49% of all studies published in

Science

and

Nature

[the two most prestigious scientific journals]

would have to be withdrawn

", he adds.

"It is quite clear that the detection is not correct," says Víctor Rivilla, an astronomer at the Madrid Astrobiology Center who works on the detection of phosphine as a marker of life in astronomical objects much more distant.

“The type of data analysis they did was very biased;

they saw phosphine because it was what they wanted to see ”, he highlights.

"It is unlikely that the original discovery will hold, the two groups that question it and their arguments are very powerful," says Ignasi Ribas, an astronomer at the Institute of Space Sciences (IEEC-CSIC).

“Even so, you will have to listen to what the authors of the original study have to say.

This is not a smear or anything out of the ordinary, quite the opposite.

Science advances in this way and if it were not like that, it would have fallen into dogmatism ”, he adds.

"There are other works underway looking at other wavelengths looking for phosphine," explains Miguel Ángel López-Valverde, from the Institute of Astrophysics of Andalusia.

“Some are already published and with negative results, like that of Therese Encrenaz, and others are theoretical work also in progress reviewing the models of cloud chemistry, which will be interesting to examine.

So there will continue to be news about this increasingly dubious attempt to detect phosphine on Venus, "he adds.

You can follow

MATERIA

on

,

,

or subscribe here to our

newsletter