Erich Schwam never forgot Chambon-sur-Lignon.

The widowed pharmacist, a Frenchman of Austrian origin, was always very reserved.

So much so that very few were aware of its hazardous origins.

Only when it was announced that after his death in December at the age of 90 he had bequeathed all his assets - almost two million euros - to Chambon, was a light shed on his past and, incidentally, on this village of the Haute-Loire that, In the most terrible of the Nazi occupation of France during World War II, he welcomed and saved thousands of Jewish children from deportation.

Among them Schwam himself, as before the town had housed Spanish republicans who had fled from Franco.

An attitude that earned Le Chambon, as the locals call this town of 2,500 inhabitants with a Protestant majority south of Lyon, being the only town in the world, together with the Dutch Nieuwlande, collectively recognized as Righteous Among the Nations by Yad Vashem, the museum of the Jewish Holocaust.

In times of new authoritarian temptations, news of Schwam's legacy has been so popular.

"Maybe it's because of the current environment," reflects Denise Vallat, Deputy Mayor for Culture of this difficult-to-access town, located on a plateau 1,000 meters above sea level.

A peculiarity that, for centuries, made it the ideal refuge for Huguenots persecuted in the 17th century or for refractory priests during the French Revolution.

At the end of the 19th century, it became a rest center for children of disadvantaged families in the south-east of France, sheltered in hostels and farms in the area.

Thanks to this, Chambon had an infrastructure that allowed him, after the Nazi occupation, to shelter Jewish children and Spanish republican exiles, with the help of a network of international associations and Protestant pastors such as André Trocmé, another Justo.

"It is a beautiful country, a bit harsh," Albert Camus wrote when he arrived in Chambon in the fall of 1942 to recover at the home of a relative from a lung disease.

Prevented by the advance of the war to return to Oran, the future Nobel Prize in Literature ended up living a year in Chambon.

There he finished

The Plague

and prepared

The Misunderstanding

.

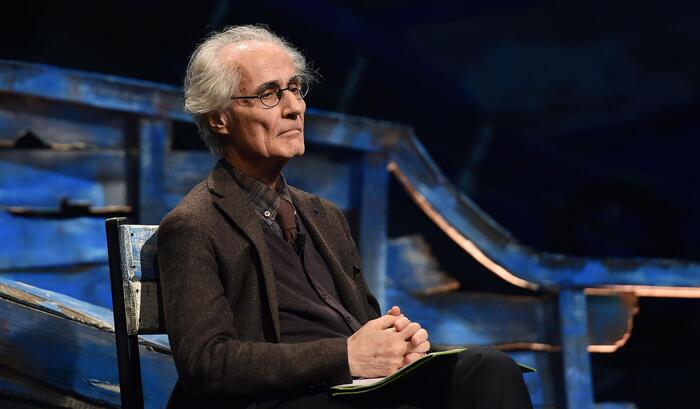

The philosopher Paul Ricoeur, a mentor to President Emmanuel Macron who taught at the prestigious Cévenol Institute, where Erich Schwam finished high school - he was one of the few refugees who did not leave after the end of the war - also left his mark before studying Pharmacy in Lyon.

Camus' stay partially coincided with that of Schwam who, according to the first data collected by Vallat and the local historian, Gérard Bollon, arrived at Le Chambon in February 1943, at the age of 12.

Vallat, a retired history teacher, and Bollon have set out to find out as much as possible about Schwam, whose heritage will be dedicated, according to his wishes, to "pro-youth actions" in education.

“What he has bequeathed to us is the fruit of a lifetime's work, not a lottery ticket, so it is very important that the villagers know who he was,” explains Vallat, who is preparing an exhibition on Schwam.

But tracking his life is being an almost detective task, because "he did not leave any letter, or information."

In his house on the outskirts of Lyon they found a manila envelope with a brief inscription: Austria, old papers.

These old passports and documents allow you to trace Erich Schwam and his parents, Oskar and Malcie, from their native Vienna to Brussels, where they left after the annexation of Austria in 1938, to end up in the French concentration camps of Gurs and Rivesaltes. where they were crammed together with thousands of Republican exiles.

Vallat and Bollon have also found out that Oskar Schwam, who was a doctor, worked in the Swiss Maternity Hospital of Elna, close to the internment camps and where more than fifty Spanish babies were born.

It was surely a Swiss maternity nurse who managed to avoid the deportation in 1942 of the Schwams to Drancy, where the collaborationist regime of Marshal Pétain interned Jews before sending them to Nazi concentration camps, and who sent Chambon to Erich and his mother a year later.

"The journey of his family is very emblematic of the one made by so many other families who passed through here," says Vallat.

It is confirmed that “almost 2,000 people - especially children, but also families or single people - passed through Chambon and its surroundings.

Which means that we can estimate that, in reality, there were between 2,500 and 3,000 ”Jewish refugees, says Vallat.

They were joined by the exiled Spaniards who began to arrive in the area in the midst of the Civil War and, above all, from 1939.

One of them was Lluis “Pepito” Gausachs, the future secretary of Josep Tarradellas.

On June 29, 1943, he fell into the worst raid Chambon ever suffered, at the Maison des Roches, one of the houses that housed Jews and other refugees.

Eighteen youths were arrested, including five Spaniards, very few of whom survived.

Gausachs was released after rescuing a German soldier who was drowning in the river a few days earlier.

Another Spaniard who was saved was Antonio Plazas, the son of a republican anarchist from Barcelona who came to Chambon from Rivesaltes at the age of 18, and who would end up teaching at Cévenol with Ricoeur.

Another Spanish woman, Juliette Usach, also has a very special place in local memory.

The Catalan Protestant doctor was entrusted in 1939 with the management of a house initially dedicated to welcoming republican women and children, although from 1941 on she would also end up taking care of the many Jewish children who came to Chambon.

The miracle of silence

The name of this "excellent woman", as the historian Bollon remembers her with affection and sadness, since she died "in misery", appears on the list of Justos de Chambon displayed in the memory center inaugurated in 2013 next to the school where all those saved children attended, often under false identities to mislead the authorities.

Today the children of the fifty asylum seekers who are waiting for papers in the town are studying in the same classrooms.

Because the “miracle of silence”, as described by Bollon by the collective action of an entire population that never spoke or denounced the refugees or those who welcomed them, has continued in this town that, decades later, would also provide shelter for Tibetan children sent by the Dalai Lama.

Or to

boat people

(Vietnamese refugees) and to Iranians who fled the Islamic Revolution of 1979. Always without bragging.

An example of this sobriety, Vallat says, there is a tradition in Chambon that is respected until today: "No street or building bears the name of anyone, not the town or personalities like De Gaulle.

Despite your generosity, there won't be a Schwam Street either.

In Chambon, deeds are priceless, or rewarding.

An unknown feat in his own country

Chambon's was a little-known feat even in France despite the fact that President Jacques Chirac, who visited the town in 2004 to denounce a spike in anti-Semitic acts across the country, called it "the conscience of the country."

In France there is a “certain amnesia, because there was a lot of collaboration and passivity of the population.

That forgetfulness caused people like Chambon to be forgotten, ”says the Madrid historian and writer Mario Escobar, author of the novel 'Children of the Yellow Star', in which he recalls this story and also that of the refugees. Spanish people.

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/IHRLG657L5HNNA7TA4HUHXYKSA.JPG)

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/57WJQXB25VEW3N6XHSY63XO6YQ.jpg)