In the late 1950s, Adger Cowans was a photography student obsessed with the idea of settling in New York.

Two things encouraged him: escaping the racism and segregation of which he was a victim at Ohio University and knowing that if Miles Davis played Carnegie Hall or Thelonious Monk at Five Spots, he could be there.

Is there a black photographer in town? He wondered.

Following the advice of one of his professors, he contacted Gordon Parks, who already worked for

Life

magazine

.

He would stay at his home in White Plains for a whole summer.

With him he learned to navigate the world;

to transform negative energy into powerful and positive images.

Years later, he would share this spirit with his colleagues from Kamoinge: a collective of African-American photographers determined to change the image that the main media offered of the black community.

Together they wanted to give an account of the place that their culture occupied in history.

His legacy, both individual and collective, reflects the power that art can wield within societies.

PHOTO GALLERY: Kamoinge Workshop: when unity is strength

"It would be correct to state that the Kamoinge workshop, while operating within the realm of denial, was forged primarily within an atmosphere of hope and not despair," noted Louis Draper, considered the soul of the group.

It is precisely from the work of this photographer, who is as committed to abstraction as he is to political assertion, that the idea for the exhibition

Working Together: The Photographers of the Kamoinge Workshop

,

which is exhibited at the Whitney Museum in New York, began.

The donation of the Draper archive to the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts (VMFA) led to a comprehensive study of the collective's impact on the history of photography in the latter part of the 20th century in America.

It is the first major exhibition of the group and brings together more than 140 images belonging to the founding members of the collective.

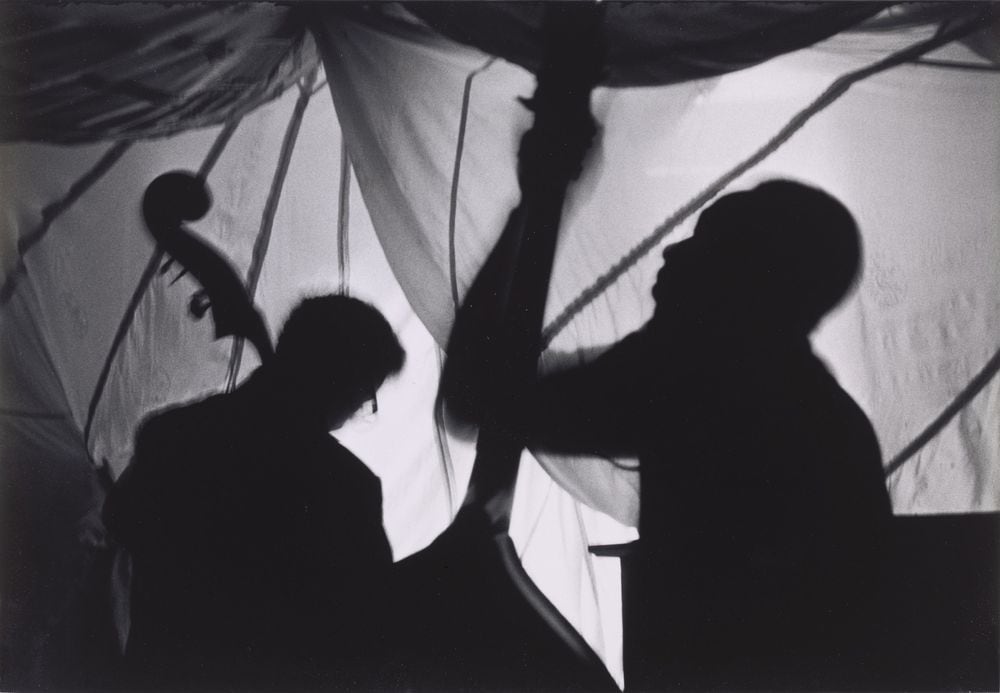

Taken during the first two decades of their training in 1963, the photographs bring together bits and pieces of everyday life in Harlem where the sound of jazz reverberates.

Portraits of the most relevant characters of their culture.

Also of the fight for civil rights and of other countries from where the African diaspora started.

Hence they chose as their name Kamoinge, a term from the Kikuyu language (quoted by the then newly appointed President of Kenya, Jomo Kenyatta, in his essay

Facing Mount Kenya

) which translates to 'group of people working together'.

Between 15 and 20 years older than most members of the group, and with an already consolidated career, Roy DeCarava became the first president of the group, a position he held for only two years.

"Although they all had a very different vision of photography, they shared and admired the aesthetics of the famous artist," says Sarah Eckhardt, curator of the exhibition.

During the July 1964 Harlem riots (triggered when a 15-year-old African-American was shot by a police officer) Newsweek magazine commissioned DeCarava to do the cover for one of its issues.

The New York neighborhood became so dangerous that none of the white photographers used to covering it had the courage to hang around its streets.

DeCarava solved it with a close-up shot of three grim, scowling men.

It was Draper and two other members of the shop: Shawn Walker and Ray Francis.

They were chatting on 125th Street when the president of their collective asked them to pose for him.

“Guys, you don't seem angry enough,” a target told them: it was the publication's artistic director.

Harlem: Hate on the Streets would be the title on the cover.

"Photography is all nostalgia," then-model and photography buff Ming Smith heard at a collective meeting in Anthony Barboza's studio.

She would go on to join the collective in 1972. “I never stopped to think about what it meant to be a woman in Kamoinge.

I suppose because we were all artists ”, he recalls in a video that accompanies the exhibition.

“It was a very pure environment.

I was safe inside ”.

To the clear awareness, on the part of all the members of the group, of photography as an artistic discipline, in its own right - at a time when very few institutions manifested it - was joined by a trend towards the experimental.

This became more manifest over the years, giving more space to more abstract and spiritual approaches.

"You have to be able to look at me and see my work," DeCarava said.

Jazz played a central role in their meetings.

The rhythm, time and improvisation associated with this musical genre became a metaphor for the creative expression of the group.

"Why was John Coltrane practicing more than 13 hours a day?" Dan Dawson wondered.

“The goal was to go from the technical to the spiritual.

Taking a photograph was a ritual act, ”Cowans recalls.

“You were capturing someone's spirit at the time.

On the contrary, when others were looking at my photographs, it offered me a window into their soul ”.

It was winter when, leaning out of the window of his home, Cowans took one of his most iconic photographs.

In it a man walks through the snow leaving behind the trail of his footsteps.

"Many people bought it because it is a black man in a white world," he highlights.

“It is loaded with that symbolism.

But for me it reflects the footprints of a man who walks.

You can hear him hum ”.

Working Together: The Photographers of the Kamoinge Workshop.

Whitney Museum.

New York.

Until March 28.

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/KMEYMJKESBAZBE4MRBAM4TGHIQ.jpg)