Modeled after arboretums or tree collections for his study, multidisciplinary artist

David Byrne

has put together the diagrams he has drawn over the years.

Through them, he seeks to understand and visualize the relationships that are established between different concepts, establishing taxonomies that reveal new meanings where the convention could have crystallized.

Human relationships, artistic currents, plants, religions, ideologies or animals are illuminated in the new light, distributed by the paper in the shape of a tree, Moebius strips, roots or solar discs.

On some occasions, Byrne accompanies the illustrations with brief explanatory texts.

Apart from his work as a musician, both as a member of the Talking Heads band or as a solo artist, Byrne is the author of

a dozen books

in which he has researched urbanism, music, sociology or technology.

Arboretum, which

Sexto Piso

publishes this Monday with a translation by Oihane Iglesias Tellería, offers us a glimpse into Byrne's mind and his way of working.

'Babelia' advances some of its pages exclusively.

What are these pictures?

Why did I make them?

Will they be interesting to someone else?

Will they do any good?

Do they have to be useful?

Well, I think it's a lot of things: fake science, automatic writing, self-analysis, satire, and maybe even a serious attempt to find connections where you didn't think there were.

Besides being an excuse to draw diagrams and figures of plants.

These drawings began a few years ago as instructions to myself in a small notebook: "Draw an evolutionary tree of pleasure," or: "Draw a Venn diagram of relationships," for example.

Orders to myself to make mind maps of imaginary territories, which accumulated for a few years until the momentum ran out.

Perhaps it was a kind of personal therapy that allowed my hand to "say" what the voice could not.

Irrational logic.

I have heard that this is what they call the application of rigor and form of scientific logic to irrational premises.

Proceed carefully and deliberately, from nonsense, undeterred, to often arrive at a new kind of meaning.

But how can nonsense emerge as meaning?

No matter how convoluted or twisted it is, it will always be nonsense.

Or not?

I feel that, to some extent, the rational thinking areas of our brains are engines of super rationalization.

I believe that many scientific and rational premises are irrational to begin with, that the object of much scientific and academic research is not, at bottom, but the elaborate justification of desire, prejudice, caprice, and glory.

I feel that, to some extent, the rational thinking areas of our brains are engines of super rationalization.

They offer us the means and the excuses for our most animalistic impulses.

They allow us to justify them first to ourselves and then to others.

"The hope that a unique mathematical solution will emerge [as an explanation of nature] is as faith-based as intelligent design," says Leonard Susskind, inventor of string theory.

This does not seem to be a very optimistic view on intelligence, but even viewed cynically, the result of years of brain activity has produced much beauty, pleasure and, in short, magnificent things.

Today, riding the train with my daughter, we watched a nature documentary on my laptop that showed abyssal creatures captured in the darkness of the ocean thanks to the glow of submersibles.

Some of them had never been sighted before, and the possibility of their existence couldn't even be thought about.

Entities that launch fireworks on time, things that live where life was thought impossible, underwater "lakes", a fish on a kind of sea stalk.

My daughter and I agreed that if the camera hadn't recorded them, they would have seemed absurd, imaginary, and incredible beings.

So, extrapolating from Mother Nature, if a relationship can be drawn, it may exist.

The world keeps opening up, showing itself, and just as we wait for it to close - as if it were a reasonable, sealed box - it reveals something completely amazing.

In fact, the result of science, and possibly its unacknowledged aspiration, is to get to know how much it is that we do not know, rather than to describe what we think we know.

After all, we are probably not sure we even know what we think we know.

If we can get an idea of what we do not know, at least we will not incur the arrogance of thinking that we know something about it.

The task of science is to map our ignorance.

Human content.

Illustration by David Byrne for his book 'Arboretum'David Byrne / EDITORIAL COURTESY SIXTH FLOOR

Human content

Young children are made of worms, snails, and doggy tails, according to a lullaby.

Following this metaphorical deconstruction of children, we can ask ourselves: what are grandparents, uncles and nieces made of?

Physical inspiration.

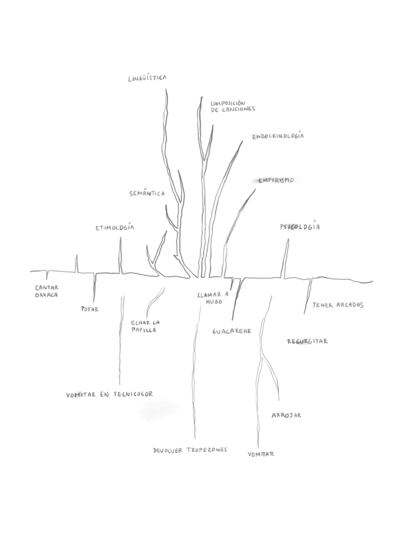

Illustration by David Byrne for his book 'Arboretum'David Byrne / EDITORIAL COURTESY SIXTH FLOOR

Physical inspiration

Psychology, speech healing, linguistics, and semantics are like dogs picking and sniffing at their own vomit.

Although there may be some jewelry out there, you never know.

What is certain is that at least you will know what you ate.

And you can determine what you will never eat again.

Vertical rhizome.

Illustration by David Byrne for his book 'Arboretum'David Byrne / EDITORIAL COURTESY SIXTH FLOOR

Vertical rhizome

Rhizome patterns - like those of bamboo - allow a root system to support many plants.

Unlike those that converge towards a stem or trunk, in this rhizomatic system the roots are more like an invisible underground network whose visible signals can manifest in numerous places.

Once a network has started to expand, it is difficult to tell where it started.

Like plants, our lives have a beginning and an end, but we can also see them as part of a larger information network, where genetic material and DNA are the elements of continuity.

Understood in this way, our lives are like plants that jump to the eye, emerging here and there as manifestations of the secret network that is the genetic sphere, an invisible rhizomatic pattern.

The disappearance of individual bodies from the network from which they come is irrelevant.

Performing arts.

Illustration by David Byrne for his book 'Arboretum'David Byrne / EDITORIAL COURTESY SIXTH FLOOR

Performing Arts

Every business is a show, one way or another.

Even bankers, who are not known for their spectacular performances, "play" the role of banker.

They dress and act in keeping with the character.

Every career requires appropriate clothing, and every profession operates according to prescribed notions of how each "character" should behave.

Most people only play a few roles in their lifetime, but one talented actor can play dozens.

The origin of species.

Illustration by David Byrne for his book 'Arboretum'David Byrne / EDITORIAL COURTESY SIXTH FLOOR

The origin of species

Every part of the world is represented in another part of the world.

Parallels and equivalences abound.

The varied creatures of the sea, made of jelly, scales and shells, are part of our archaic biological memories: once we were all like this, and the world we have created is, in a way, the reconstruction of that deep memory.

Moral senses.

Illustration by David Byrne for his book 'Arboretum'David Byrne / EDITORIAL COURTESY SIXTH FLOOR

Hutcheson's Moral Senses

The Scottish theologian and philosopher of the 18th century believed that there was an intimate connection between the perception of beauty and the solidity of morality.

The more beautiful things we see, the better people we will be.

He even established a hierarchy of beauty and corresponding moral precepts.

Imagine the kind of divine moral creatures that museum watchers would be!

These are your categories, in ascending order.

In an effort to make my own contribution, I have placed the appropriate settings and occupations next to their categories.

Types of face.

Illustration by David Byrne for his book 'Arboretum'David Byrne / EDITORIAL COURTESY SIXTH FLOOR

Arboretum

Author: David Byrne

Translator: Oihane Iglesias Tellería

Editorial: Sexto Piso, 2021

Format: Hardcover.

206 pages.

24.90 euros

Look for it in your bookstore

You can follow BABELIA on

and

, or sign up here to receive

our weekly newsletter

.