Eva's mother dies on the floor of a filthy hut on a death march in the Czech Republic • "Throw a slice at her too, I ate both" • A chilling testimony

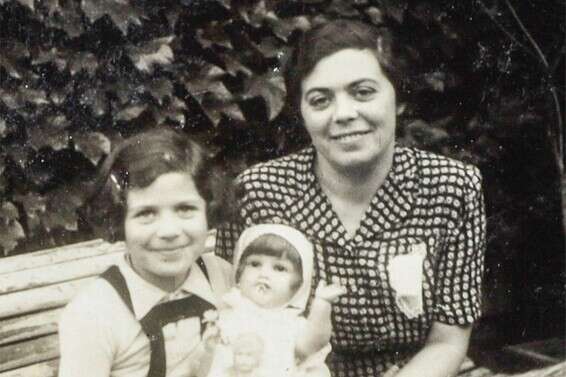

Eva Arban

Photo:

Yehuda Peretz

"If I could paint, I would paint my childhood like a rainbow. I remember forests, mushrooms, picking strawberries."

This sentence, which seems to describe an optimistic and happy painting that is supposed to characterize the reality of children's lives, has over the years become the farthest thing from the inferno imposed on Oh Arban.

The beautiful youth she had hoped for was replaced by concentration camps and a long death march, during which she experienced the worst of all and in the end was miraculously saved.

Some of the things she said during the interview, she said, did not dare to tell to this day.

Preferred to try to forget.

But in the course of things she decided not to skimp on even the most difficult descriptions, to go back to everything that had been burned into her.

Eva was born in Czechoslovakia to an established, only and happy family.

The family used to celebrate all the holidays, Passover and also Easter, God seems to her like a good grandfather who sees everything she does - and therefore should behave nicely.

In those years, anti-Semitism was hardly felt in Czechoslovakia, the Jews were free to do as they pleased, and yet, in 1935, the family moved to the capital, Prague, where the warning lights began to light.

Her father, Indrich Levitt, a chemist by profession, developed a patent from the world of glass materials, but as a Jew he was forbidden to register it in his name, but only in the name of a friend.

"In, 1938, the whole generation of parents asked, 'How long can Hitler last longer?' Johan Wolfgang von Goethe.) I remember I went to buy ice cream and there was a sign, 'Jews and dogs are not allowed in.' I went in, I bought the ice cream, I heard Hitler's shouts on the radio, but I was convinced it could not be - it would pass.

"One day a large vehicle arrived. We were evicted, the villa was taken from us, and we moved into a shared apartment for the Jews. But that was also fine - two rooms and a kitchen in Prague. Dad said 'what they took from us does not matter, we will work and buy a new one. Czechoslovakia now "In trouble, what if we run away? We'll go through it all together and start from the beginning."

In December 1941, the Levitt family was taken to the next station, the Terezin ghetto.

From there, Eva has no special memories, and for her it was another place to live, without knowing what to expect.

"I mostly remember we were crowded. You were never alone in Terezin, it wasn't always pleasant but we got the best out of it."

In October 1944, when shipments to Auschwitz began, the picture changed beyond recognition.

"The Germans announced that a new ghetto was needed and all men aged 50-18 leave to build a new ghetto. This is actually the last time I saw Dad. After a few days the Germans announced that the new ghetto was ready and we left with things we still had left. We rode a normal train, not of "Beasts, and when three days later she was arrested in Auschwitz, my mother, Marta, said, 'Wow, we will not stay here. It's a camp for criminals.'"

The shouting, the barking - and the smell

Oh, so a 14-year-old does not forget the sights, sounds and smells that greeted the family: "The screams, the barking of the dogs, the awful smell, sweet and warm, that we thought came from some factory or something the men work in, terrible chaos. My mother's friend Marezin, who was already in Auschwitz as a stewardess, took me and said, 'If you are asked how old you are, say. '18 And so my mother and I went through the selection on the right. I remember the procedure of taking off my hair, wet clothes, terrible. We had no clothes. "With stripes like they always show on TV in movies about Auschwitz. They brought us clothes that were stolen from the prisoners' bags. I got a huge blue dress, but it was good for me because I didn't have underwear, socks and a tank top."

The reality of the gas and the crematoria was hard to digest: "You could see something flying like a leaf, and people would say, 'Oh, this is Moshe's leg.' I did not grasp it. I am there physically, but not spiritually, I did not believe it was happening in reality. A woman started telling me that she imagines making a surfer, how she slices everything - onion, sausage, you can smell it, she does not cook, but at least she has raised the morale of the people in the hut. "Whenever we talked about the Holocaust, it was in such shades."

At that time, Eva and mother Marta tried to get every bit of information about Father Indrich.

"We understood that they were burned, that they were not, that they died of gas. But that was not true. My father eventually died of an illness in January, 1945 right at the end of the war."

At the end of October 1944, Eva and her mother were transferred to the Gross-Rosen labor camp, and at the entrance were forced to receive a mysterious shot.

"It was a shot like a horse, one huge needle for everyone, we did not know what it was. The next day I got up with a swollen and pus-filled hand, until now you can see it, it's a sign from there actually," she shows me her left hand.

Following the injection, her condition deteriorated.

"I had a fever for a few days. My mother volunteered to work in the kitchen and with a knife she heated on the fire they opened my hand and took out my pus."

Continuing the recovery process, she recounts another moment she will not forget: "The camp commander saw that I was without shoes in minus 20 degrees, and sent me to a hut to wait there. I realized that the guard lived there and that he needed to keep the hut, but the commander brought me a pair of shoes. You know "When I tell this to children in Germany, I hear their cries of astonishment. Not all Germans were murderers."

Farewell - and a journey of survival

At the end of January, 1945, as Allied tanks and planes roared around, rumors began to circulate that the war was coming to an end.

For the camp people, this had bitter consequences.

"One morning jeeps arrived and everyone jumped 'Here the Americans are coming', just a question were the SS men with dogs. Within 15 minutes we organized a thousand women and went on a death march that lasted until April. Every day you go 30-25 Km, and those who can not walk - shoot him, immediately.

"In front of me was a girl who had an epileptic seizure - and she was shot. When a bullet passes you, it's like he's hitting you. We took a big step and walked on. At that moment you have no time to feel, you continue, because if not - then you will also be shot. The feelings, you are alone, you are in some fantasy, a nightmare. "

In April 1945, after more than three months of grueling marching, only 250 of the 1,000 women survived.

"We came to a camp like this, in a hut. The whole floor was covered with wood chips and white powder and stinking to disinfect, people lay in it, the fibers of the wood got into clothes, just awful. And there, inside the hut, my mother died. She knew she was going to die, She told me. She had a terrible leg wound. I did not want to believe, I talked to her, I held her with me in this horrible smell. To this day I did not tell it, I did not want to remember. How good that a person forgets ...

"In the evening, a German who distributes bread came to dinner, and I talked to my mother and held her. She thought my mother was asleep, she also threw her a slice of bread, and I ate two. Even after death, she gave me the bread as a gift."

The night after parting from her mother, Oh survived, digging into a pile of grass with a strong smell of cows to keep warm.

"Everyone would do it, and the Germans would go through and check the grass with a pitchfork."

She fell asleep, and it was probably the strong smell that saved her from the German patrol dogs.

"When I woke up I had someone checking my pulse, I was like dead, he told me 'you' live 'and went to get me something to drink."

Oh remember that in the morning she came to a large farm in the middle of nowhere.

She noticed a railroad track and started walking along it until she saw a house.

"I was afraid to come in stinking, with lice, I did not know who was there, it could be that they were Germans, I just walked a few meters and fell asleep. After a while he sat down next to a German soldier and gave me a drink from his canteen, he had coffee with sugar and milk and a piece of bread." "April 23," he said, adding that he was going to look for a job with a local farmer. "It turns out that it was a soldier who ran away. To this day, I see that face. A young boy who missed his mother."

Eva's journey lasted another three days, and after an exhausting 80 km walk she found herself in a small Czech village. On the way to it she was saved, and not for the first time:

I heard the soldier's weapon load that came out to me, and in that second another soldier came out, grabbed his hand and said 'Let her go, she will fall alone, do you not see what she looks like?'.

He hit me, I rolled towards the river and fainted. "

The chain of events that helped her survive continued, when a woman by the river noticed her by the river and decided to take her home.

"I woke up in a clean bed and I hear people say 'she's going to die.' There was a midwife in the village who took milk from a woman with a baby, and they only gave me milk for a few days and so they saved me. When I woke up they asked me who I was, I said I was a gentile, and they were amazing. The war told me, "We knew you were Jewish."

Years later, the same couple received the Righteous Among the Nations award in Jerusalem.

Absorption pains

Eva recovered and found her aunt at the end of the war.

She lived with her for a year and then moved to an orphanage on her own initiative, where she met a friend from the Terezin ghetto and her life was filled with happiness.

The two went on to study nursing and Eva was already planning to continue her life in Australia, but by then she had met Peter Arben, her future husband.

"We dressed nicely, two beautiful girls, and went to a cafe on the river to drink to life in honor of the State of Israel, after we had previously heard David Ben-Gurion at the declaration of independence. Suddenly Peter arrived there with two other boys. I knew him in Terezin. Although he is ten years older than me But when we met in the cafe and I was 17 we started dancing, and the next day he came to the orphanage. Without much talk he handed me over to him and left me a note 'From today you live with me'. He knew I loved him, in love with him. To this day I have the "This note. It actually brought me back to life. I could not have gone through death and these moments and this period without it."

With the rise of communist rule in the Czech Republic, manifestations of anti-Semitism returned, and the young couple arrived in Paris on fake visas, where he married and continued on a ship to Israel, when Eva was eight months pregnant.

"We came to Israel, we went to Nesher, Peter's brother said he had a small apartment. It was very difficult in the first days, then we rented a room in Kiryat Haim and our daughter was born. Peter worked in the bay and we had nothing. We decided to go to the Negev, to start over, even though they looked at us About crazy people. "

When Eva and Peter arrived in Ashkelon, they faced a crisis of a different kind - prejudice against an entire generation of Holocaust survivors.

"We had native friends who were in the Palmach, and told stories from the past.

Peter worked in the war for Messerschmitt, was among the prisoners who made defects in parts to sabotage planes.

When he wanted to tell something - silence him.

They told him 'you went like sheep to the slaughter', I was sick of hearing that, we did not go like sheep to the slaughter.

"I loved the company, the people, but they presented it to us as a fact. At the time I thought I had something with my heart. I got a sedative from the doctor, so I would have the confidence if they said 'you went like a sheep to the slaughter'. I suffered terribly, but it changed As soon as they caught Eichmann. (1960 gallons of tears my generation cried, a lot of people said sorry to us later, that's why I did not want to talk. We were always a foreign plant. That's why my children do not know Czech. The Czechs came in With the food and the trips when we showed them. "

Four years ago, Peter died at the age of 96. The couple has three children, nine grandchildren and 16 great-grandchildren.

Eva will tell her story at the annual Holocaust ceremony at Kibbutz Yad Mordechai, which is produced by the World Zionist Organization and by "Havatzelet Cultural and Educational Institutions of Hashomer Hatzair."

"There was a midwife in the village who took milk from a woman with a baby, and they gave me only milk for a few days and so they saved me. When I woke up they asked me who I said I was a gentile and they were amazing. At the end of the war they told me 'we knew you were Jewish.'

"Before me went a girl who had an epileptic seizure - and she was shot. Do you know what it's like when a bullet passes you? As if he was hitting you. We took a big step and walked on. You have no time to feel you are continuing, because if not - you will also be shot."