Scarlet White, the voice of Jean Genet.

The memory of a voice has a color;

Genet's had something bright and at the same time playful.

I still hear it.

Voice worked by tobacco, a little hoarse, almost feminine, but a smiling voice.

Over time it became thick, calm and ever present, urgent.

He will write in

A Captive in Love

: "Like all voices, mine is forged, and if the forgeries are not guessed, no reader is aware of their nature."

I was far from realizing its special effects.

There was a certain constancy in that voice, a tone that varied little.

He never spoke out loud and, even when angry, only expressed his exasperation in chosen words.

It was natural to him.

But when he wrote he heard his inner voice, which must be different from the one he used in public.

Sometimes he would mutter or emphasize certain words to make their importance felt better.

He accompanied them with precise gestures as if drawing faces and body expressions.

The voice of falsehood.

The voice of truth.

The right voice.

He went from one to the other without warning.

He was proceeding, naively, in such a crude way that it produced laughter.

Lying is doing pirouettes.

He would agree with what Cavafis said: "The truth only belongs to the victors", and added: "The truth is not enough, but the poet even testifies to what he has not seen."

Genet did not recognize himself "in the thread of evidence" (René Char);

far from it, everything seemed complex to him and he distrusted everything and everyone except those he loved.

Thus he passed from one excess to another and it did not bother him.

He was the man of the given word, a word he gave very rarely.

Of the rest, signature, contract, promise, he gave him for mocking and laughing.

At no point did I feel that his voice was "fake", except when he was imitating people.

More than 40 years later, I still have it clearly in my memory.

I listen to her, go back to the past and see again that sunny spring morning, May 5, 1974;

I was thirty years old and he was the age that I am today, when I write these lines: 64 years.

Much more than his writings, to which I return often, it is his voice that accompanies me the most.

For me it was the voice of a real man, not that of a liar, a liar, a gamer or a comedian.

Especially not that of a saint.

He spoke to me on the phone, and I endeavored to represent him.

I had only seen one photo of him with the Black Panthers in America.

I remembered his boxer nose and his bald head.

I wasn't sure I'd recognize him if I ran into him on the street.

I had heard of him when he took a stand for black prisoners in America.

It was in July 1969, at the Pan-American Festival in Algiers.

Some men came from walking on the moon, and we, incredulous, preferred the company of black militants with Angela Davis at the head.

It was there that I first heard the name of Genet from the mouth of Jean Sénac, a French poet who became an Algerian, murdered in 1973 in Algiers because he was homosexual, because he was a rebel, because he annoyed a harsh military regime allergic to poetry, to free thought, to creative imagination.

"My name is Jean Genet, you don't know me, but I do, I've read it and I'd like to meet you ... Are you free to eat?"

I said to myself: it's funny, the world upside down.

A myth of French letters that invites me!

I could'nt believe it.

He was vaguely aware of his jokes, his polemics, his scandals, and his forbidden works.

When I was writing my first novel,

Harrouda

, between 1970 and 1972, I discovered the

Thief's Diary

, which a friend had recommended to me.

"Read it, it talks about Tangier, a Tangier that neither you nor I knew."

Indeed, I was surprised and at the same time intrigued by what that man related about his trip from Barcelona to Tangier.

That reading shocked me, but it was a healthy, formidable shock.

"My name is Jean Genet, you don't know me, but I do, I've read it and I'd like to meet you ... Are you free to eat?"

I said to myself: it's funny, the world upside down.

A myth of French letters that invites me!

Jean Genet wanted to meet me!

Of course he was free!

I would have canceled everything to accept your invitation.

It was the only time he spoke to me about you.

The tuteo was in him immediate, except with the people he wanted to have at a distance.

I knew I had read

Harrouda

, published in 1973, in Maurice Nadeau.

He had talked about her on a France Culture broadcast.

His intervention was published in

L'Humanité

.

A bookseller friend on Rue de Rennes told me a few days later, but too late to find the newspaper on the newsstands.

He told me that Genet messed with Sartre.

"

Harrouda

by Tahar Ben Jelloun,

Une vie d'Algérien

by Ahmed,

Le Cheval dans la ville

de Pelégri,

Le Champ des oliviers

by Nabile Farès," Genet had declared on May 2, 1974, "are the books one would have to read to to know the misery of the emigrants, their loneliness and their misfortunes, which are also ours.

[...] It is necessary for me to speak, and I will speak of these voices that are more lucid than plaintive, since our intellectuals, who are still stupidly called

thinkers

, drain the buck;

those who are supposedly the best keep quiet;

one of the most generous, Jean-Paul Sartre, seems to have made a mistake and indulged in it.

He dares not utter a word, a word that could help those voices of Tahar Ben Jelloun and Ahmed.

But Sartre is no longer anyone's thinker, except for a picturesque band already disbanded ”.

These words had initially surprised me, as they were inaccurate: my novel was not about the misery of immigrants, but about the story of a boy who discovers sexuality between the cities of Fez and Tangier.

Genet had only retained the figure of the child's mother and that of that old prostitute turned beggar that the children nicknamed "Harrouda."

While waiting to read the whole article, I said to myself "I have to thank you" and sent a rather banal letter to Gallimard with my address on the back of the envelope: "Maison de la Norvège, Cité Universitaire, boulevard Jourdan, Paris XIV" .

I was far from imagining that he would answer me and I could not guess that he would choose to phone me.

In the University City we did not have a telephone in the rooms, only a bell to notify us.

Then you had to go down to reception to take the call.

I was in pajamas and while I was getting dressed, only one fear invaded me: that the caller had not already hung up.

They called me rarely.

They must be, I thought, my parents or my brother surely passing through Paris.

When I picked up the receiver, his first sentence came out at once.

Not a single hesitation, not the slightest silence between words.

As learned by heart, as recited by a comedian with no right to be wrong: "My name is Jean Genet ...".

He asked me to meet at the L'Européen restaurant, opposite the Gare de Lyon.

I took the subway with the excitement of going to meet the writer I would never have expected to meet one day.

But lo and behold, disturbed by the invitation, I go to the wrong station and find myself at the Gare du Nord.

I went back down to the subway, thinking again about the pages of

the Thief's Diary

, a book that had left me knocked out by its virulence, its cruelty and its audacity.

I remembered the spit, the lice and the swear words: “The lice inhabited us.

They gave our clothes such animation, such presence, that when they disappeared, it seemed they were dead.

We liked to know, and feel, swarm the translucent beasts that, without being domesticated, were so good to us that another's louse disgusted us.

We hunted them, but hoping that on the day the nits would have hatched.

With our nails we crushed them without disgust and without hatred ”.

This passage had stuck in my memory because it accurately returned to those nights spent in the army disciplinary camp hunting bed bugs (when one squashes them, they give off an unbearable smell) and lice that hid in the sheets, since our heads they were systematically shaved every other day.

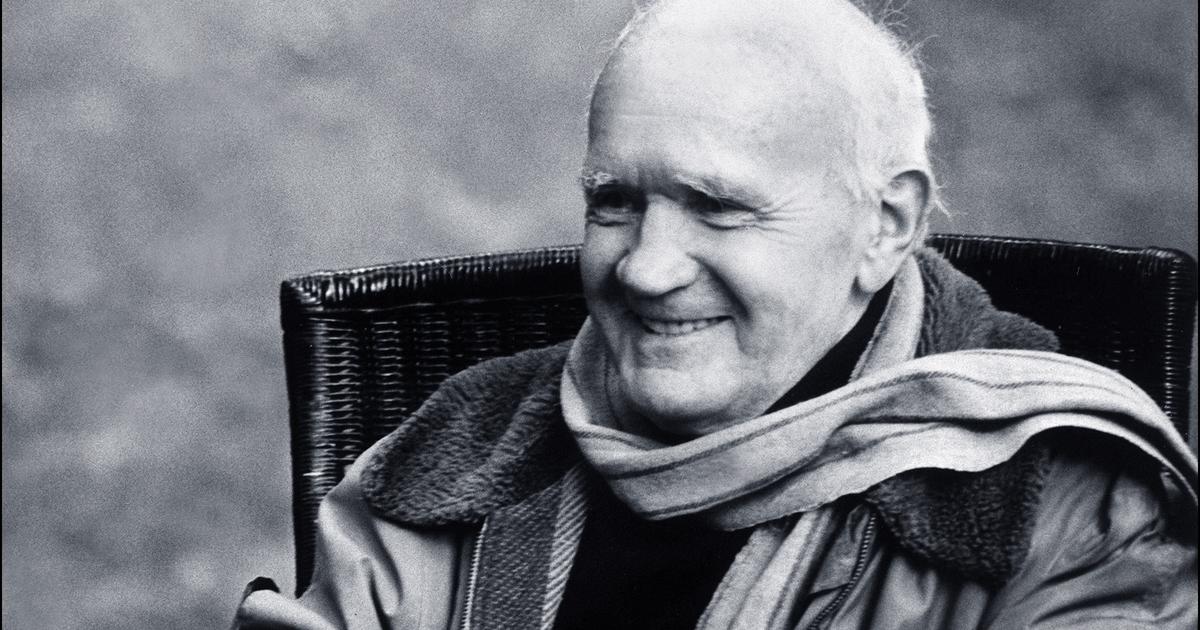

Tahar ben Jelloun, novelist and intellectual, Goncourt Prize winner, BERNARDO PÉREZ

After having traversed all of Paris by metro, I was finally very late.

It was a particularly sunny day, Genet was on the sidewalk, a book in hand.

I was surprised by the fresh pink of her cheeks, a caramel pink.

A smiling baby, small in size, bright white shirt, not very clean beige pants, worn suede jacket, traces of nicotine on the fingers.

He was smoking Panter cigarettes, the smoke smelled awful.

As I walked into the restaurant, I thought I was right to tell him that I admired his work.

Without getting angry, he told me: “Don't ever talk to me about my books again;

I wrote to get out of prison, not to save society;

I have saved my skin by applying myself like a good schoolboy, you know, that's all ”.

I was shocked, a little taken aback, not knowing how to fix the blunder.

I had had certain illusions and I thought that a great writer would not speak of his work that way.

It was the naive side of my beginnings in literature.

But I confess that this surprising violent reaction helped me enormously in my life and in my work.

It was the first time I had met a writer who could not bear to have his work mentioned in front of him.

It was very strange.

I asked him why.

He looked at me and said: "What is important, a man or a work?"

He placed before me the work in his hand, a book in Arabic.

He told me: "It's Thousand and One Nights, it would be nice if you translated them."

I replied that there were already good translations of that book.

He did not insist and began to speak to me in more detail: “I come from Palestine and, ultimately, from Jordan and from the Palestinian camps.

The Jordanian police arrested me and then expelled me.

I was talking about Black September, about the responsibility of the little king;

in short, I was not welcome.

Anyway, you have to know that what I've seen is horrible;

yes, horrible, people have to know what happens there.

I have seen dehydrated children, mothers implore heaven, combatants go out at dawn to fight the occupier;

I have seen such things that I have written a text that Arafat has asked me to do.

It has been translated into Arabic.

I do not have it, but I would very much like to pass it on to you so that you could tell me if it is well translated, you understand, for the Palestinians.

The words have to be precise, without contradictions, it is important ”.

He ordered a cane and mash.

The waiter said: "Mashed, with what? Meat, fish?"

"Mince".

He told me: “In Paris, you can't eat a bowl of puree.

I hardly have any teeth left, so I can't chew the meat, I eat puree;

but you have to ask for meat, or there is no mash.

Although, you, take what you want.

You are my guest ”.

During the rest of the meal, at no time did he talk about

Harrouda

or his intervention in France Culture;

He told me about the Palestinian camps, about Hamza, a Palestinian fighter he had met, about Hamza's mother, the children who played with punctured balls, the dust, the lack of water, the dignity of women.

He insisted on this last point and then told me: “Something has to be done, the Europeans need to know what is happening there;

I promised that I would help them by informing the people.

The other day I received a letter from Claude Mauriac de

Le Figaro

, he asked me to write something about I don't know what anymore and he gave me a whole page, I telephoned him proposing to tell him about my trip to Palestine.

He marked a waiting time and then he said: "No, what I ask of you is a literary page!"

But I have nothing to do with that, with literature!

What I want is to give testimony, to denounce!

Literature!

What a hoax! "

I thought I was right to tell him that I admired his work.

Without getting angry, he told me: “Don't ever talk to me about my books again;

I wrote to get out of prison, not to save society;

I have saved my skin by applying myself like a good schoolboy, you know, that's all ”.

Speaking slowly, as if dictating a text learned by heart, he told me a phrase similar to the one I now read at the beginning of

A Captive in Love

: “In Palestine, more than in other places, it seemed to me that women possessed a quality more than men. mens.

No matter how brave, brave, attentive to others, every man is limited by his own truths.

To theirs, women, on the other hand not admitted to the ranks but responsible for the work in the fields, add to all of these a dimension that seems to imply an immense laugh ”.

I realized that, for him, it was the Palestinian women that we should speak to as a priority if we were to do something together.

It was even the secret reason for that meal.

I was not disappointed;

on the contrary, it stimulated me.

I myself was quite committed to the Palestinians in Paris and had just lost a friend, Mahmoud Hamchari, killed at his home by having his phone exploded.

The Israeli secret services proceeded in this way, at that time, when they wanted to eliminate this or that representative of Palestine in Europe.

I had written a poem in his memory, which became a poster distributed by Belgian supporters of the Palestinian cause.

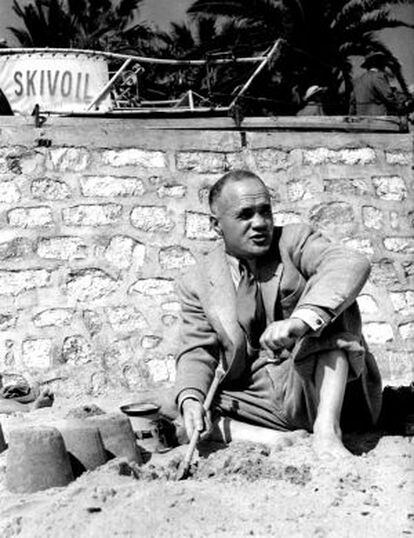

Jean Genet on the beach in Cannes, during the 1957 film festival.georges dudognon / album

I immediately proposed to Genet that I be commissioned to write an article on the matter in

Le Monde

, where I had just begun to collaborate.

He looked at me stunned and then said, "I don't think you want to post something that is going to upset your Israeli friends."

He was convinced, and he was for the rest of his life, that the French media were "under the thumb of the Zionists" ...

The day after our meeting, I visited Pierre Viansson-Ponté, the editor-in-chief of

Le Monde

, for whom I had to write in that newspaper since my friend François Bott introduced it to me.

Viansson advised me to meet Claude Julien, who ran

Le Monde diplomatique

.

What I did immediately.

Julien was an elegant man, courteous and attracted to others.

He told me: “That interests me a lot;

I reserve the last page of July for you, it is widely read;

I await your writing ”.

Then a real workshop with Genet began.

He came almost daily to my room at the Maison de la Norvège and spoke to me.

I took notes.

When I could not imagine the places, he would take a pen and draw the field with some lines.

He wanted to be precise, exact, and he repeated the same phrase several times.

I wrote almost under his dictation.

He would reread me later;

With a red pen, he crossed out the phrases he did not like.

It was going to last about two hours.

Quite the opposite of the

Monde des livres

, which had taught me to be quick by sometimes asking me for an obituary just before closing.

I knew how to work urgently.

I had already done reports and sent my articles by telex because the news does not wait.

This did not prevent the great Jacques Fauvert, director of

Le Monde

at that time, from repeating: "Information has to be verified more than once before being published, even if we have to appear after the others."

They were other times, other demands.

I realized that, for him, it was the Palestinian women that we should speak to as a priority if we were to do something together.

It was even the secret reason for that meal.

I no longer remember how many mornings and afternoons we work, Genet and I, that text.

Very early one morning, he got up at six, he called me simply to exchange a word.

He said, “You know, it's about the Palestinians, men and women without a homeland;

We cannot also mistreat them with incorrect or improper words, they deserve our best words;

that is why we have to be precise, very precise, and not leave any deficiency or ambiguity in the text ”.

I must have typed the article a dozen times on my old typewriter.

He was rereading it with a red Bic pen in hand;

He underlined certain passages, wrote in the margin, crossed out some of his own words, read aloud, and then handed it back to me for retyping.

I was no longer a journalist in his eyes, but an accomplice who was commissioned to convey a message.

He was passionate, determined to do whatever it took to bear witness to all that he had seen there and to the inhumane conditions in which the Palestinian refugees lived.

He took his role so seriously that he had lost his sense of humor.

He was serious, impatient and, when he paused, he ranted against the French press that turned its back on the misfortune of those people.

I must have typed the article a dozen times.

He was rereading it with a red pen in hand;

I underlined, wrote in the margin, crossed out, read aloud, and then handed it back to me for retyping.

I was no longer a journalist in his eyes, but an accomplice who was commissioned to convey a message.

When the article was finally finished, after innumerable revisions and corrections, Genet put a

sine qua non

condition

for its publication: Azzedine Kalak, the representative of the PLO in Paris, had to give me his permission.

And here they were already gathered around the text, in my tiny room in the University City: Jean Genet, Azzedine Kalak and Mahmoud Darwich, who, passing through Paris, had joined us.

I would read in French and then translate into Arabic for Azzedine Kalak and Mahmoud Darwich.

They were proud and touched by all the attention Genet paid them.

Mahmoud knew him a little already, they had met in Amman.

We started a conversation between the four of us, in a mixture of French and Arabic.

Genet took everything so seriously that he came to seem a little too meticulous, too rigorous, which even made Azzedine and Mahmoud smile, especially the latter, who had a great sense of humor.

In front of them, Genet was totally devoid of it.

But I still retain the memory of that meeting of a generally good humor and of a very fraternal relationship.

How could he imagine then that Azzedine Kalak would be assassinated four years later, in that same city and probably by the Iraqi secret services?

Genet certainly idealized the Palestinians and their cause, but he knew what he was doing;

This was not his first fight, and his fight alongside the American blacks had taught him that one had to be very demanding and be very vigilant if you wanted to win the game.

I took the letter to Claude Julien, who told me that he was very happy to publish a text inspired by Jean Genet and his fight for the Palestinian cause.

The article appeared in the July 1974 issue. I had very little reaction to its content;

In compensation, my friends kept telling me that I frequented whom they considered a great writer.

No matter how much I rectified and said that the Genet I knew was more of a militant than a writer, they kept telling me that luck was smiling on me.

"Not only has he written about you," one of them told me, "but now he writes with you."

Later I understood to what extent it was Genet who always chose the people he frequented and not the other way around.

It was untraceable, unavailable, out of reach.

When we saw each other, he did everything possible to avoid what he called the "pesky", a category that encompassed tax agents as well as old acquaintances who hoped to reconnect with him.

As for friendship, it was intractable.

Translation by Pedro Gandía Buleo.

You can follow BABELIA on

and

, or sign up here to receive

our weekly newsletter

.

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/GNE3LQFGRVCODPOHCRBEVT7PYE.jpg)

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/WGGYQRRT55FZ5JCXE3P4MZ2XGI.jpg)