María Martinón got on a regional train in Germany and sat with a box on her knees, unaware that there was a dead child inside.

It was March 15, 2018. Martinón had picked up the package at a German scientific center and was on his way to Burgos, to the National Center for Research on Human Evolution, of which he is the director.

The expert only knew that she was carrying a block of Kenyan earth, from which two teeth that did not look like monkeys were showing.

After three years of research, the contents of that box are revealed to the world today on the cover of the journal

Nature

, the temple of world science: they were the remains of a boy who died and was buried with care about 78,000 years ago. It is the oldest known tomb in Africa and one of the most shocking evidence of one of the most specifically human behaviors: caring for the dead.

When Martinón arrived at the Munich airport security checkpoint that day in 2018, an agent asked him if he could open the box. "I'd rather not," replied Martinon, consciously paraphrasing the protagonist of the nineteenth-century tale

Bartleby, the clerk

. "You couldn't see anything in the airport scanner," recalls the researcher. Whatever was in there was disintegrating. Upon arriving in Burgos, his team began a meticulous work to find out what was inside that fragile block of land. "It was like excavating the ghost of a child, the shadow of his bones," recalls Martinón.

The human remains appeared in 2017 in Panga ya Saidi Cave, an archaeological site located near the Kenyan coast. The restoration work carried out in Burgos gradually revealed a bone here and another there, until the definitive discovery was reached: someone made a hole about 78,000 years ago, placed the corpse of a child lying on its right side and buried it. The arrangement of the bones also suggests that the little boy, about three years old, had a kind of shroud in his grave and something similar to a pillow. Martinón believes that "the extreme delicacy and tenderness" with which he was treated shows that the boy meant something to his group. "He is wrapped up as they would have wrapped him in bed when they put him to sleep," he details. Researchers have named the kid: Mtoto,a word that means child in Swahili.

Paleoanthropologist María Martinón shows the remains of Mtoto to archaeologist Emmanuel Ndiema, in Nairobi.Pilar Fernández Colón

Africa is the cradle of humanity and a good part of the scientific community believes that modern human behavior also emerged there, that which separates us from the rest of the animals.

However, outside Africa there were already known burials much older than that of the Mtoto child.

Archaic

Homo sapiens

burial sites

dating from 90,000 to 130,000 years ago

have been identified at the Qafzeh and Skhul sites in Israel

.

In the Tabun cave, also in Israel, the burial of a Neanderthal woman was found, probably about 122,000 years old.

There is still no explanation for the gap of some 40,000 years between the earliest known tombs in Africa and those in the Middle East.

One of the possible reasons is that, simply, older graves have not appeared on the African continent because not enough has been excavated.

Another option, Martinón points out, is that there were funeral rituals that did not leave archaeological traces.

"If, for example, they left the dead in the air and began to dance around them, that leaves no trace," he hypothesizes.

“And another possibility that I would not close is that this type of behavior did not originate in Africa, but in the Middle East.

Why not? ”, He adds.

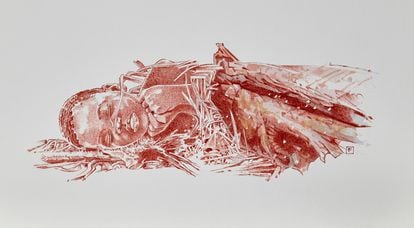

Artistic recreation of the tomb of the child Mtoto. Fernando Fueyo

Martinón collected the box with the child's remains at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, in Jena (Germany), from one of its scientists, Emmanuel Ndiema, also head of archeology at the National Museums of Kenya. Ndiema explains that the inhabitants of the Panga ya Saidi cave -

Homo sapiens

, like modern humans - must have been hunters and gatherers, with access to the resources of the savannah and those of the nearby ocean. According to Ndiema, the Kenyan site suggests that "the evolution of cognitive abilities and social relationships may have occurred earlier than previously thought."

French paleoanthropologist Bernard Vandermeersch led the excavations of the Israeli Qafzeh cave more than half a century ago. The 84-year-old researcher based in Madrid applauds the new work, in which he has not participated. "It is a very beautiful and important discovery, because we knew almost nothing about burial practices during the Middle Stone Age in Africa, although it is not surprising to find such a burial in that period 78,000 years ago," says Vandermeersch. "It is important, but it does not change what we already knew about the behavior of

Middle Palaeolithic

Homo sapiens

," he adds.

Until now, the two oldest possible burials in Africa were the remains of a child from about 69,000 years ago found inside a hole in Taramsa (Egypt) and the bones of another child, from about 74,000 years ago, found in 1941 in Border Cave (South Africa).

Martinón's team believes that these two graves, along with the new one at Mtoto, suggest that

Homo sapiens were

already preserving the corpses of their children at this time.

General view of the Panga ya Saidi site in Kenya Mohammad Javad Shoaee

British archaeologist Paul Pettitt recalls that many of the sites with presumed graves were investigated decades ago, so "it is sometimes questionable whether they are authentic burials and not skeletons preserved by chance." Pettitt believes that the sophisticated techniques used on the Mtoto boy's remains do “unequivocally” show that it was a deliberate burial. "Burial was not the standard way of treating the dead, so the question arises as to what strange circumstances caused it to be chosen for some individuals," reflects the researcher, from the University of Durham, in England.

Pettitt, author of the book

The Paleolithic Origins of Human Burial

(Routledge publisher), argues that burials were very rare until a few thousand years ago and were probably only used after rare deaths. Maybe Mtoto was a special kid for some reason. María Martinón took the boy's remains back to Kenya on May 22, 2019. What remains of his bones is kept in the fossil chamber of the National Museums of Kenya, in Nairobi, along with the remains of the first

Homo habilis

and the skeleton of the so-called Turkana boy, a

1.6-million-year-old

Homo erectus

. “We left it there, with the greatest”, celebrates Martinón.

You can write to

us

at

manuel@esmateria.com

or follow

MATERIA

on

,

,

or subscribe here to our

newsletter

.