When in 1925, the photographer Margaret Watkins (Ontario, Canada, 1884 - Glasgow, United Kingdom, 1969) set out to portray herself in her studio in New York's Greenwich Village, curiously she did so through an ellipsis: she would do without her figure. A hat, gloves and a small bag would serve to reveal an enigmatic presence, crowned by a network of shadows and three Renaissance prints where time seemed to have raged. At that time, the artist was at the peak of her career. Through his careful compositions and a skillful mastery of light, he had managed to translate the codes of modernism into the language of advertising. His exquisite domestic still lifes filled the pages of the

Vanity Fair

and they served as a teaser for large firms such as

Macy's

department

store

and the

J. Walter Thompson

advertising agency

.

However, the mysterious self-portrait that occupied her foreshadowed her decline as well as her fate;

a path shrouded in gloom, where the artist's trail would be lost.

PHOTO GALLERY: The enigmatic woman with a hat

“His trajectory was short.

But of a deep complexity.

She was a woman ahead of her time.

However, a victim of her time and a series of personal adversities, her work disappeared for six decades ”, highlights Anna Morin, curator of

Margaret Watkins, Black Light

, an exhibition produced by DiChroma Photography that rescues the figure of the Canadian photographer.

It is exhibited in the Kutxa Kultur Artegunea room in San Sebastián, and will arrive at the CentroCentro room in Madrid next June within the PhotoEspaña 2021 program.

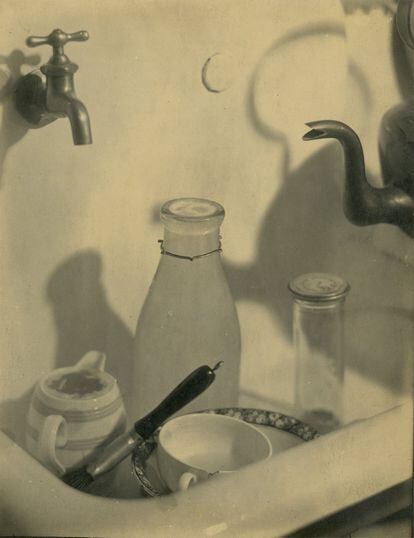

The Kitchen Sink

It is possibly the best known photograph of the photographer. Image with which much later, in 2013, Canada recognized the artist's contribution to the country's photography history, using it as a postage stamp. Made in 1919, the still life reveals the beauty of some utilitarian kitchen objects. Still unwashed, with food scraps and nicked, "the objects should not arouse an interest in themselves, but merely contribute to the design," explained the photographer. The balance established between the masses of light and shadows, in a harmonious composition dominated by diagonal lines, demonstrates the skill of the author, as well as her interest in form and in creating new rhythms.Even so, the intimacy that the image gives off transcends the formalistic intention and seems to speak of Watkins's refusal to continue "domesticated to death", using her own words. It alludes to the difficulties of women to free themselves from established roles.

'Sink', 1919. Margaret Watkins / Joseph Mulholland Collection, Glasgow

Structured in five sections, the exhibition covers the artist's career. It is accompanied by a magnificent catalog that introduces the photographer through a writing by Joseph Mulholland, a key figure in the last stage and in the future of Watkins. They met in 1966, in Glasgow. The gallery owner was then a law student and journalist, intrigued by the mysterious figure of a woman who lived in an old house, opposite his home. A misunderstanding led to their meeting. That enigmatic lady would turn out to be Watkins. “She was a fascinating woman. She lived alone in a 17-room house that she only left after dark. He had suffered from agoraphobia for five years. The children of the neighborhood believed that a ghost or a witch ”, remembers Mulholland in telephone conversation.“He was possibly the most cultivated person that I had ever come across; a master of the Victorian art of conversation. He guided the talk from topic to topic effortlessly. His vocabulary was extraordinarily rich. If there were 17 similar words to describe something, she chose the one that contained the most accurate nuance ”.

One day Watkins summoned her neighbor to help her draw up her will. “He also asked me to keep a box with his belongings. He said something about some photographs. I thought he was referring to family memories. He made me promise not to open it until after his death. " Watkins died in 1967. The box would be forgotten in his confidante's closet. It took four more years to open it, when the Scotsman found a legacy of hundreds of copies and negatives. “I thought I knew Watkins well, so in a way, I was disappointed. I realized then that he always missed two issues: his past and photography, ”Mulholland laments. Something surprising, especially when the author must have known that the young man wrote regularly in one of the most widely circulated newspapers in Scotland,and precisely about photography.

'Self-portrait', 1925. Margaret Watkins / Joseph Mulholland Collection, Glasgow

The exhibition begins in 1914, when the artist enters the school of Clarence H. White, co-founder of the Photo-Secession and one of the main exponents of pictorialism in the United States - she will later work there as a teacher. "It is here where he acquires all the richness and complexity of the visual language that he will later capture, when he settles in New York and practices commercial photography with great freedom of interpretation," Morin points out. “It squeezes all that fabric that I had acquired with White in a very fresh way. And sometimes his work borders on abstraction ”. Watkins was fascinated by music. He said that in his most abstract photographs he traced the visual construction on the construction of a score. Hence

Domestic Symphony

be the title of his best-known series. “Her work sometimes finds resonances with

Georgia O'Keffe

. He was in the eye of the artistic hurricane in New York ”.

In 1925 White died suddenly. His disappearance would be the first step in the artist's decline. "The photographer was not only a titular figure but also a moral support for Watkins, despite the fact that she was always a very independent woman, capable of successfully running her own studio in New York," says the curator. It was the unpleasant dispute with White's widow, over the ownership of copies that her mentor, that set her up for a trip to Europe. He would end up winning the lawsuit, but that trip, which was supposed to last three months, lasted 40 years. He never returned to America again. The old Glasgow house, where he settled in order to care for his three elderly aunts, would become his slab. Mulholland remembers that the photographer kept her bags ready to go.The outbreak of war and another series of personal adversities made it impossible.

Even so, once in Europe, he traveled to Moscow, Paris and London. Aware that a single small detail is enough to exalt the beauty of the world, the Glasgow shipyards and the advertising motifs that he found in the cities would serve as an excuse to play with rhythms, geometry and abstraction. he is ahead of his time and his work takes a turn towards the new German objectivity ”, highlights Morin. The last chapter of the exhibition is made up of a series of photomontages made in order to be used as textile design. "If he had continued his artistic career, I am almost sure that he would have been interested in cinema," says the curator. "We find the precepts of the language of fragmentation, assembly and repetition."

His last photo appears to be a self-portrait.

The shadow of a woman in a hat is projected on a staircase.

Morin makes a comparison with her: “Curiously, the image winks at another photographer who tended to disappear, not be visible, as Vivian Maier was.

And whose work came to light in 2007 ”.

Margaret Watkins, Black Light.

Kutxa Kultur Artegunea Room.

Tabakalera.

Saint Sebastian.

Until May 30.

You can follow BABELIA on

and

, or sign up here to receive

our weekly newsletter

.