The Mexican writer Julián Herbert, author of "La Casa del Dolor Ajeno." MARIO RUIZ / EFE

In 2014, when the Mexican writer Julián Herbert (Acapulco, 50 years old) was investigating in Torreón, Coahuila, for one of his future books, he asked several taxi drivers in the city if they knew who was responsible for a massacre that occurred there in 1911 against the Chinese community. "My general [Pancho] Villa," says one. "It must have been the Zetas, right?" Says another. A third party nods at him to indicate that he has no idea. "What about you?" He asks. "You know something?"

Herbert knew a lot. It wasn't Pancho Villa and it wasn't the Zetas. A few months after the beginning of the Mexican Revolution, it was Maderista rebels and citizens of Torreón who committed genocide there: they murdered 303 Chinese migrants between May 13 and 15, 1911. “The massacre of the Chinese from Torreón is an episode revealing and buried of the Mexican Revolution ", Herbert writes in

La Casa del Dolor Ajeno,

published by Random House in 2015, a" historical antinovela "that gathers academic or judicial sources on this silenced event in the collective memory.

The book regains political relevance this week due to a government event.

On Monday morning, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador will travel to Torreón to apologize to the Chinese community for this massacre, the second of three forgiveness events he has planned this year (the other two are to the Yaqui and Maya indigenous peoples ).

In this case, although the xenophobia against the Chinese community grew in the years of the Porfiriato, the president would have to admit on Monday the responsibility of the men he admires, the Maderista revolutionaries.

He would have to offer forgiveness on behalf of his friends in history, not just his enemies.

More information

López Obrador's first pardon

Julián Herbert lives in Saltillo, Coahuila, and spoke with EL PAÍS about what happened in Torreón, the fibers that the president touches with this silenced event, and the type of reparation he would prefer for migrants.

Question.

How is it explained that this migration of Chinese traders and farmers has reached northern Mexico?

Answer.

To understand this, you must first understand that there was a great migration of Chinese, specifically Cantonese, between 1849 and 1949. For a century, from the southern provinces of China, Canton, around eight million people emigrated.

That is almost the population of Honduras.

It was a massive migratory event due to a confluence of dire events in China.

But for the Cantonese migration, it was not about emigrating to Mexico.

It was about emigrating to America in a broad sense: to the south of the United States, to the north of Mexico, to the islands of the Caribbean.

In the specific case of Mexico, migrants arrive with the intention of crossing into the United States.

Those who remain in Mexico are concentrated in the northwest of the country, in Sinaloa, in Sonora, and this number increased after the prohibition act in the United States, at the end of the 19th century, which prohibited them from entering.

Then the Chinese become the first

wet

.

In reality, the first illegal migration from Mexico to the United States is not by Mexicans, but by Chinese.

Q.

And why do many of them stay in Torreón, Coahuila?

R.

Torreón is a city that has a very particular history. The cities of Mexico existed for centuries or at least dozens of years, and Torreón received its city status until 1907. At the time when the great Chinese diaspora happened, the city was also being founded. Here comes someone very particular, a Chinese philosopher and politician named Kang Youwei. He became China's interior minister during the Hundred-Day Reform, which is a time when a young emperor seized power and tried to change economic thinking. They give him a coup, they imprison him, and Kang Youwei is sentenced to death. Kang first takes refuge in the United States, but brings a large investment, because he steals part of the treasure. Someone tells you that in Mexico there is a city where you can invest, because it has just been born, and it is Torreón.Kang Youwei is associated with the economic leader of Torreón and begins to invest in the city around 1908. The prosperity of the Chinese community of Torreón is sudden, and it is the only community that competes economically with European migration and the Mexican bourgeoisie. That's a super determining factor for what happened next. The Chinese community in Torreón is not the largest, but it is rich. The only Chinese bank in the country was in Torreón.but it is rich. The only Chinese bank in the country was in Torreón.but it is rich. The only Chinese bank in the country was in Torreón.

Q.

How was a synophobic discourse woven there at the same time?

R.

The traditional thesis has been that the common people, in a moment of spontaneous violence, murdered the Chinese of Torreón. I do not agree with that thesis. First, there was already a xenophobia built from the United States, and most of those ideas come from a series of texts that were published in New York and Boston in the late 19th century. That xenophobia had a direct path with the Mexican elites and particularly with the elites of Coahuila. Many of the children of these elite families, and even the teachers who taught in this region, were forged in Bridgewater, and other colleges in Massachusetts and New York. Anti-Chinese xenophobia appears in the Mexican press, but refers to La Laguna (the area where Torreón is), since the end of the 19th century. The first anti-Chinese document published in Mexico is from Coahuila, from 1876,before the Chinese came, saying 'we don't want them to come'.

Then, with that speech another is mixed, which is the speech of anarchists and trade unionists, especially through the railways. The railwaymen had a problem with the Chinese when they started to arrive. The Chinese start to work, like any migrant, for very low wages. So the trade unionists are outraged because that makes wages go down and they reject migration. And ultimately, this discourse is incorporated into popular classes. One of those involved in the massacre is a vegetable seller. The Chinese had bought a lot of land, had put up vegetable gardens in the east of the city, and had taken over much of the vegetable stalls. That speech is mixed with an issue of economic competition.

Q.

The Mexican Revolution starts and the Chinese were caught in the crossfire between the Porfiristas and the Maderistas.

Is it true that the Maderistas justified the massacre by saying that the Chinese were on the side of the Porfiristas?

R.

That was an argument that came up very quickly. The first "investigation" was commissioned to a Maderista soldier who had no legal training. He is the first to say that the Chinese attacked the troops. That is absolutely untrue. First, a doctor named Walter J Lim toured the orchards together with a Maderista military man, and in a document signed by both they attest that there were no shots from that side to the other. The bullets only went in one direction. Later, the US consul in Torreón participated in the tours as well, and also said that the Chinese were systematically persecuted and executed, and that they had no weapons. And there are also forensic reports. The corpses were treated, and there are statements from a nurse describing the corpses.She says that most [of the Chinese killed] are shot in the chest and in the head. They cannot have been killed in combat, because there are no shooters with such precision as to hit everyone in the heart and in the head. It shows that they were executed. The other is that many of them had their heads split off, with a blow of a machete, with a force that could only be given from a much higher height. That is, they were executed with a machete from the horses.they were executed with a machete from the horses.they were executed with a machete from the horses.

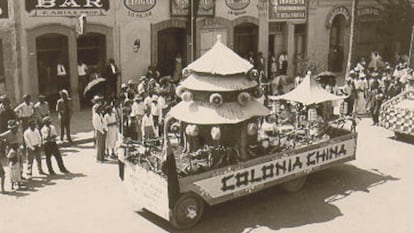

On February 20, 1912, the Chinese residents of Torreón held a parade to demand protection from the authorities.

Q.

Who was Dr. Walter J Lim and why is his life a symbol of what happened in May 1911?

R.

Lim is a character that excites me a lot, the emotion always wins me over when I talk about him. Lim is a doctor, and he finds out about the massacre on the morning of the 15th, because he is busy treating patients from the civil war. Lim at one point goes out to smoke a cigarette, and someone comes and says 'hide yourself, they are killing Chinese in the street'. And Lim doesn't hide but grabs a stretcher and goes out into the street. What moves me is that, his gesture. It seems to me that in him is the other dimension of the tragedy. Torreón is a complex city, but there were people who tried to save the Chinese, people who were Chinese like Lim, and others who were not.

Lim is also someone about whom we have a lot of data.

We still don't know the names of many of those who were there, we don't know anything.

But he did because he had a very particular leadership in the city.

He was not an economic leader, but rather as a moral leader of the community.

That is why you are allowed to testify later.

The little we know about the Chinese side of the massacre is in the Foreign Relations file, there is the statement of Dr. Lim.

For me it is an invaluable voice, because it is the voice of the defeated, the voice of the dead.

Q.

Why is Lim's house a symbol of the silence that has existed in the face of the massacre?

A.

Well, his house later became the Museum of the Revolution.

It was not the house I lived in, but it was like a

chalet

where he had his garden, and his house was cared for by his sister, who is the only woman mentioned in the documents. She was alone, the Maderistas break into the house, and probably abuse her, or so Lim suggests in her testimony. It does not say so directly. The Maderistas also mistreat their children. They finally manage to save themselves, and the place still stands. Now, in modern times, it is the Museum of the Revolution. For me, what is there is a kind of double looting: the looting of the house, and the looting of the memory. The massacre is not represented in the Museum of the Revolution, despite the fact that there, that house, was part of a genocidal persecution against the Chinese in the city.

Q.

The president is going to offer his apologies to the Chinese community this Monday. Have there been other gestures of forgiveness since 1911 or is this the first from a president?

R.

10 years ago there was a redress ceremony [through the City Council], which was promoted by the city's chronicler, Sergio Corona. Well, they put up a plaque and put up a sculpture of a Cantonese gardener. But the plaque was stolen, and the sculpture was torn down. I don't know what will happen now with this event. When I went to present

La Casa del Dolor Ajeno

in Torreón, they closed all the cultural centers to me and threatened to cut off the light of the place where I was going to present it. The torreonence does not want to see this story. They told me to my face, 'this story is ours, it's not yours.' That is the attitude of many torreonences, at least of the upper class. And the other thing someone said to me was, 'You, in this book, speak ill of my grandfather.'

Q.

And what do you think of this gesture of forgiveness by López Obrador in Torreón?

A.

I'm still not quite sure that a forgiveness ceremony is the best.

It seems to me that reconciliation is more important.

What does that mean?

One of the prejudices against the Chinese was that they did not mix.

And that has proven to be false.

The Chinese community has also entered the veins of this country.

We come from the Chinese as we come from other communities.

Today they are part of our miscegenation.

It may not have been as widespread a root as others, but it is to recognize them as part of our own mestizo heritage.

I also feel that President López Obrador has a sensitivity about what irritates the elites. He is very clear about the nerves that are on the surface of the elites, and this is one of them. That is very clear to me: touching this story from the Presidency of the Republic is a very hard kick in the shin for a sector of the elites. Torreonence society is much more willing to dialogue with this story about the massacre than the bourgeoisie there. Well, part of the bourgeoisie there includes the leader of FRENAA (Gilberto Lozano), who is one of the owners of Soriana. So I don't think this is completely unrelated to that vision either, because López Obrador has a political vision.

But for now, it seems to me that it is a transcendent event because it gives a forum to this issue, and for me this story is very important.

More than the political event, it interests me that this issue is gaining national relevance.

Q.

Do you see a parallel between this massacre of 1911 and the violence of the Mexican state today against migrants in the north of the country?

A.

Yes, of course, and I talk about that in the book. The underlying problem is not only that historical moment, but that this deals with an imaginary of the country today. Not only the mistreatment of Central American migrants, which is, of course, the most serious, the most obvious. I am also concerned about how Asian migration continues to be received in Mexico, because anti-Asian prejudices remain. I live in Saltillo, which is a city where there is a Korean community, and it is as if nothing had happened. There is still a racist language. But in this city there has also been a long project against power, from the Church, regarding migration: there is a Casa del Migrante that is strategic, and until recently we had a bishop who was a great figure for migrants.

I insist that more than talking about forgiveness, it seems to me more important to talk about reconciliation.

How could you do it?

Years ago, there was a concrete commitment to pay the Chinese government three million pesos in gold.

That will have accrued very impressive interest by now.

I am not saying that the Chinese government is paid, but it does seem to me that this is something concrete.

There is an economic amount that is owed as compensation to migrants who suffered violence.

A fund can be created, for example, for the protection and relief of migrants.

If the offer of forgiveness includes compensation that will create a fund for migrants, it would seem like a super decision, an effective reparation and aimed at preventing that from happening again.

Well, something like that would happen ... if we lived in another country.

Subscribe here

to the

newsletter

of EL PAÍS México and receive all the informative keys of the current situation of this country