Passengers on flight FR4978 from Athens watched with bewilderment as their plane turned sharply as it began its descent over Vilnius, the Lithuanian capital. Even more so when a fighter from the Belarusian Army came alongside in order to escort the aircraft not to its intended destination, but to the Minsk airport. But a young man - who, visibly frightened, began to rummage through his luggage to hand over his phone and laptop to his companion - realized what was really happening: they were going to arrest him. The 26-year-old man was the journalist and activist Roman Protasevich, wanted by Belarus since he went into exile two years ago in fear for his life. "The death penalty awaits me here," he said when the Belarusian security services took him from the detained plane along with his girlfriend, Sofía Sapega,of Russian nationality and a student at the European University of Vilnius.

But why would a government like Alexandr Lukashenko's - highly questioned for clinging to power after the fraudulent 2020 elections and sanctioned by the European Union - risk such a spectacular operation, forcing the landing of a civilian flight, supposedly to capture a dissident? "It is true that this is a very extreme method of repression," says Nate Schenkkan, strategy director at the Freedom House think tank. “But the fact that a government is capable of endangering the lives of so many passengers, using a fighter and threatening international civil aviation indicates the feeling of impunity that drives these regimes when they persecute dissidents. They feel that there are no consequences for it, ”he adds. The main reason, Schenkkan believes, is that Lukashenko is not setting a new precedent,but following previous precedents.

In February, three months before Belarus mobilized its military aviation to stop the Protasevich flight, Freedom House published a report (with Nate Schenkkan as a co-author) warning of the growing tendency of authoritarian states to persecute exiles beyond its borders and collects data on more than 600 cases of kidnappings, murders, disappearances and fraudulent extraditions carried out between 2014 and 2020 by some thirty countries. Freedom House attributes a third of the incidents collected to China and ranks Russia as the one that perpetrated the most murders or attempted murders of dissidents in the period studied, but accuses less powerful countries of using similar tactics. For example,Thais who fled their country after the 2014 coup d'état have watched with fear as prominent compatriots in exile disappear or die in strange circumstances. In Rwanda, the Paul Kagame regime hatches complex plans to arrest opponents abroad: Paul Rusesabagina, famous for saving dozens of Tutsis during the 1994 genocide and immortalized in film

Hotel Rwanda

, denounced last August his "kidnapping" at the Dubai airport after luring him from his exile in Belgium to give an alleged talk.

Turkey, which in recent years has brought home more than a hundred exiles linked to Kurdish nationalism and the Islamist organization Fethullah Gülen - accused of the attempted coup in 2016 - has done well by putting pressure on the countries that they welcomed them, either through operations carried out by the secret services.

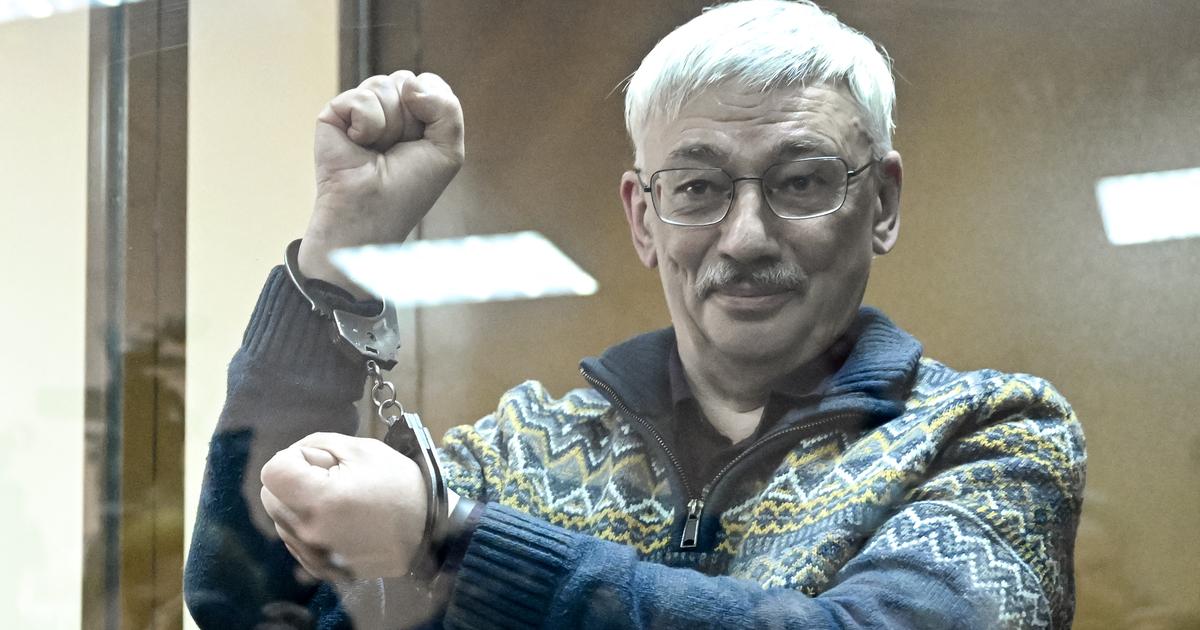

Rwandan opponent Paul Rusesabagina, in the courts of Kigali, Rwanda in September 2020.STRINGER / AFP via Getty Images

The Turkish refuge

Interestingly, over the last decade, as Turkey became more authoritarian and more aggressive abroad, this country has also become a haven for thousands of dissidents fleeing dictatorships in the Middle East, the Caucasus and Central Asia. But after the fled, his pursuers have arrived. Between 2009 and 2016, six former Chechen commanders and fighters were assassinated; in 2015 the Tajik opposition leader Umarali Kuvvatov was shot in the head (after an attempted poisoning); In 2017 and 2019, the shooting of two gunmen killed two Iranian dissidents, one of them a deserter from the Ministry of Defense. Last November, an exiled Uighur (persecuted Muslim minority in China) was shot,and he survived what he himself defined as an attempted murder instigated by Beijing. He claimed that the Chinese authorities had forced him to spy on his compatriots from the Uighur diaspora in Turkey under the threat of torturing his mother.

Among all the murders of exiles that occurred in Istanbul, there is one that stands out for its boldness and brutality: that of the Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi. If the previous crimes were committed by hitmen who later fled - which makes it possible to deny their involvement to the governments that allegedly ordered these killings - Khashoggi was assassinated inside the Saudi Arabian consulate in Istanbul by members of the Saudi security apparatus. who traveled

ex professo

from Riyadh and then tore the body to pieces.

Saudi

heir to the throne and

de facto

leader

, Mohamed Bin Salman, approved the assassination, according to a US intelligence report declassified in February.

Yemeni Nobel Peace Prize winner Tawakkol Karman at a protest in Istanbul over the disappearance of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi in October 2018.Anadolu Agency / Getty Images

“These incidents are just the tip of the iceberg; every murder, every delivery, every arrest, spreads like a wave through the diaspora and silences many more, ”says the Freedom House report. Because that is the objective: not so much the individual prey as to teach a lesson and serve as a threat about what can happen to those who criticize their country of origin. “Transnational repression weighs heavily on the exiled opposition. It causes fear and some leave activism. Others go anonymous or restrict their comments to certain topics to avoid crossing the lines imposed by the authorities. Others, however, continue, ”says Schenkkan. But, of course, getting around is more difficult when you suspect you're being spied on.

"Another pattern that we have well documented in Middle Eastern countries (for example, in Bahrain or Egypt) is detaining family members to force dissidents to return to their country of origin," says Diana Eltahawy, deputy director of Amnesty International for the region.

For example, last year, psychiatrist Amr Abu Khalil, the brother of an Egyptian opposition journalist exiled in Turkey, died of a heart attack in an Egyptian prison after his jailers denied him medical care.

These situations, explains Eltahawy, originate in the context of a decade in which - as happened in Egypt or Libya - there was a certain openness, followed by an intense repression of the dissidents who fled the country.

And the repression, he points out, has spread abroad.

Digital repression

Although the persecution of dissidents beyond their country of origin has always existed - think of Trotsky - the Freedom House think tank report argues that one of the reasons that have encouraged this aggressive policy of transnational persecution has been the impunity with which The United States conducted its war on terror, with more than a hundred kidnappings around the globe and hundreds of attacks (according to a report by the Open Society Foundation to identify victims of the war on terror). Israel's campaign of dozens of "targeted" killings in the past 20 years, from Hamas operatives in Gaza to nuclear scientists in Iran or even a Palestinian engineer in Malaysia, has also fueled.

The apparent alibi that anything goes against terrorism has led many authoritarian governments to take note and use the label of terrorist to justify their attack on dissidents. Because, although kidnapping and murder are the most brutal methods of transnational repression, they are not the most used. There are others such as pressure on the authorities of the countries that host exiles or the abuse of the International Criminal Police Organization (Interpol). In this matter, authoritarian governments use fear of terrorism, in addition to the anti-immigration and anti-refugee discourses of the populist right, which predispose Western governments to hand over those individuals on whom there is any suspicion of illegal activity, no matter how minimal. .

The jurist Manuel Ollé Sesé, who has just published

Passive extradition: a fundamental human rights approach

(Agapea), gives an account of this growing trend according to which certain governments monitor the movements around the world of their "legal prisoners" in search of "a complacent territory" that guarantees their extradition request. “Authoritarian states construct a criminal act and adorn it in such a way that when that person arrives in a country a red notice from Interpol skips and, indeed, it seems that he or she has committed a crime. Only when you start to investigate does one realize that this extradition request is fraudulent, "he explains. But even then the punishment for the dissident begins: "There are many ballots that prevent him from being imprisoned, especially if he lacks roots in the country in which he is located." This is what happened in 2017 to the Turkish-Swedish journalist Hamza Yalçin,accused by the Government of Recep Tayyip Erdogan of crimes of opinion and ties to terrorism, who spent several weeks in detention in Spain before the Council of Ministers rejected the request for extradition to Turkey. It also happened in 2017 to the German-Turkish writer Dogan Akhanli, whom Istanbul claimed for alleged links to terrorism, and who was arrested during a vacation in Granada. "It is a very pressing problem and on which the international community must reflect," says lawyer Ollé Sesé: "Interpol should review its system, and this type of fraudulent lawsuit should not pass even the first filter. Judges, prosecutors and lawyers must be involved and ensure that fundamental rights are respected.In the event that the requested individual is finally extradited and his rights in the country of origin are not respected or he is subjected to torture, governments must take measures, such as demanding his return or cutting off all cooperation for future extraditions ”.

Tajik activist Sharofiddin Gadoev shows a photo of his cousin, opponent Umarali Kuvvatov, at a forum in Oslo in 2019. Julia Reinhart / Getty Images

Among the forms of persecution, the one that, by far, is used the most is the digital one, so much so that it is unquantifiable.

The Internet has changed everything.

He has given exiles a loudspeaker to keep in touch and remain influential within the countries from which they have had to flee.

At the same time, stresses researcher Marcus Michaelsen in his study

Silencing Across Borders

(silencing across borders), "digital technologies have allowed governments to expand their tactics of extraterritorial repression, quickly monitoring and responding to diaspora activities." This includes the use of advanced spying technologies, hacking accounts or exploiting social networks: there are serious suspicions that Saudi Arabia spied on the mobile of Jeff Bezos, the richest man in the world, owner of Amazon and

The Washington Post.

. In 2015, a Twitter engineer was accused of receiving Saudi money in exchange for providing information to help locate exiles. The persecution also translates into false complaints to YouTube or Facebook to remove accounts of opponents or, the most common formula, organized harassment campaigns by trolls and bots. “Professionally, this has consequences. If you get hacked, they can erase years of research and work. It also has its economic cost, because if you suspect that the phone or computer you use is infected, you have to change it, and replace it with a safer, more expensive one, when exiled dissidents are not usually people in a good economic situation ", explains the Azerbaijani journalist Arzu Geybulla, residing in Istanbul. Herself, studious of the subject,She received hundreds of threats for her opposition to the recent war between Azerbaijan and Armenia, forcing her to temporarily shut down her social media: “Personally, it has a devastating effect. The volume of disqualifications and (especially for women) threats of rape or against your family can have serious consequences for your mental health. And even if you close your profiles, the stress level continues because you know they keep talking about you and attacking you ”. In other words, digital repression works.And even if you close your profiles, the stress level continues because you know they keep talking about you and attacking you ”. In other words, digital repression works.And even if you close your profiles, the stress level continues because you know they keep talking about you and attacking you ”. In other words, digital repression works.

An unpunished persecution

That is why certain States have launched themselves to persecute their exiles: because it is an effective weapon to fight against outbreaks of opposition and, especially, because nothing happens to do so, which "encourages these governments", denounces Eltahawy by Amnesty International. The poisoning of former Russian spy Alexander Litvinenko in London in 2006 "probably" occurred with the approval of the government of Vladimir Putin, according to the UK investigation. The lukewarm response to the assassination seemed to have a knock-on effect: in the following years, more than a dozen Chechen opponents were assassinated; also ex-spy Sergei Skripal suffered a poisoning attempt, again in the UK in 2018,and the Chechen-Georgian Zelimkhan Khangoshvili was found dead with two shots to the head in a Berlin park in 2019.

Former Russian spy Alexander Litvinenko, hospitalized in London a few days before he died.Natasja Weitsz / Getty Images

Agnès Callamard, who investigated the murder of Khashoggi as the United Nations special rapporteur for extrajudicial executions, warns in one of her reports that the use of extraterritorial violence against people perceived as dissidents is increasing, precisely due to "impunity" of the one enjoyed by those who commit this type of crime. For this reason, it urges that national governments and the UN review their protocols, since they have “an obligation” to protect the lives of those who are in their territory, whether or not they are citizens. “When [the Crown Prince of Saudi Arabia] Mohamed Bin Salmán ordered the assassination of Khashoggi, there was a lot of media coverage and a lot of noise. However, the situation has changed very little for Mohamed Bin Salmán, personally, or for Saudi Arabia, geopolitically. And Paul Kagame,the Rwandan president gives interviews to international media about how successful the operation to kidnap Rusesabagina was. They don't even feel like they have to apologize for these things, ”laments Schenkkan of the Freedom House think tank. Furthermore, these types of actions not only harm attempts to form an opposition in exile, but also the very democracies that host dissidents, since repression across borders, Schenkkan argues, increases the levels of opposition. violence and corruption (with bribes or pressure on institutions, security forces, intelligence services or even courts). "Undermine the rule of law," he stresses. In the case of Protasevich, the Freedom House researcher proposes a severe and unambiguous answer: “You have to be tough in the face of this type of behavior.Not to impose sanctions only on individuals, but to be willing to block entire sectors of the Belarusian economy that support the illegitimate president Lukashenko: fertilizers, fossil fuels ... If something like this is not done, then presidents like him will say to themselves: 'OK, they do a lot. noise, but in the end the cost is not very high ”.

Subscribe here

to the weekly Ideas newsletter.

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/EJZDZLMCZUH6BYBVJJWXE5DLVU.jpg)