Humans were already killing men, women and children in a widespread and indiscriminate manner 13,400 years ago.

It is one of the conclusions of a study that has applied modern forensic techniques to the remains of a late Paleolithic burial.

Most of the injuries were caused by thrown weapons, pointing more to attacks by other groups rather than violence within the community.

The study authors also point out that those buried there did not die in a single confrontation, but in successive attacks.

During the construction of the Aswan Dam to govern the floods of the Nile (Egypt), in the 1960s of the 20th century, a cemetery with the remains of 61 people was discovered in Jebel Sahaba, in northern Sudan. Known as Cemetery 117, his remains were brought to the UK before the water from the reservoir drowned them. Many showed marks of violence. There is evidence of collective violence against other groups also in Asia, Europe and Africa itself, but none as old as this. Archaeologists of the time considered this burial to be the first great witness to war between modern humans.

Now researchers from the British Museum (where the remains of Cemetery 117 are preserved) and the French universities of Bordeaux and Toulouse have once again checked the skulls and hundreds of bones for any signs of violence. And they have found many more than were known before. The results of their forensic work, published in the scientific journal

Scientific Reports

, show that the majority, 67% of those buried had wounds of violent origin. That amounts to doubling the number of wounded remains found in studies from the 1960s. In addition, they have found a hundred injuries not observed with the techniques of that time. In many, there are still splinters of the stone tips embedded in the bone.

67% of adults and half of children have violent bone injuries

The main author of the study is Isabelle Crevecoeur, paleoanthropologist at the University of Bordeaux and the French CNRS (equivalent to the Spanish CSIC) and confirms the high percentage of people with injuries: “It is 73.7% of women and 75% of the men.

Which in essence shows that women and men were indistinctly attacked ”.

And the percentage could be even higher, since not all fatal wounds reach the bone or have gone through the skull.

This refined analysis gives key clues about what this violence was like against each other. “When you compare the location of the projectile marks and their frequency, the only difference has to do with the fractures. In women, most of the scars are related to defensive injuries while in men the fractures occur in the bones of the hand ”, details Crevecoeur. And he explains the different injuries: "This is the type of injury you have in hand-to-hand combat and the differences may reflect an instinctive reaction in this situation, when men would be more likely to face the attacker while women could be protecting themselves" .

Also, half of the children in the 117 cemetery have the mark of violence on their bones.

Although in some cases bone injuries could be due to accidental blows, in most cases they are wounds caused by a weapon.

"Trauma occurs mainly in young children (probably less willing to defend themselves), and projectile marks are registered mainly in the skull (where they would penetrate more easily than in adults due to the thickness of the cranial bones)", he explains the French scientist.

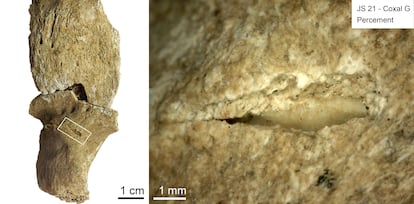

On the left, bone with the mark of an injury.

On the right, you can see the lithic splinter of a projectile still embedded in the bone.Isabelle Crevecoeur / Marie-Hélène Dias-Meirinho

This forensic analysis of the past also shows that half of the injuries were caused by thrown weapons, such as arrows and spears. This reinforces the idea of indiscriminate aggression from the outside. For years, various archaeologists have maintained that the attack on Jebel Sahaba was a single event. However, Crevecoeur and his research colleagues maintain that there is sufficient evidence that this late Paleolithic community suffered periodic raids and ambushes. One of them is that many of those buried have already healed injuries along with others that have not. That is, they had already suffered seizures before the last

perimortem

injury

, the one that would end their life.

In addition to the healed wounds, Crevecoeur gives two other arguments in favor of his thesis. For one thing, several of the individual burials were reopened to bury someone else years later. Nor does the whole of cemetery 117 fit them. "When you have a burial related to a single event (a massacre, an epidemic ...) the part of the population that dies is not the normal one that you would find in any other cemetery," he says, in reference to the layers of society that tend to die the most in wars, such as the young and old and the adults. “We look at the demographic profile of the cemetery and it does not match that of a single-event burial, of a mortality crisis. Jebel Sahaba's profile is that of a normal cemetery ”.

Why were members of this community of gatherers and hunters in the Nile Valley killed? The head of the collection of remains of Jebel Sahaba in the British Museum Daniel Antoine is betting on climate change that occurred coinciding in part with the passage from the Pleistocene to the Holocene, the current period. In a note from the museum, he asserts that "competition for resources due to a change in the climate was most likely the cause of these recurring conflicts."

José Manuel Maíllo, a prehistorian at the National Distance Education University, has investigated other prehistoric burials of violent origin such as that of Nataruk, in Kenya.

For him, the climatic causality of the violence seen in cemetery 117 is not founded.

"They give the explanation, somewhat hackneyed, that it is because of the climate that limits the obtaining of resources," he says.

In Maíllo's opinion, they should explore the keys that could lead to “a conflict between sedentary or semi-sedentary hunter-gatherer groups at a time of climatic instability”.

"Most of the empirical evidence on intergroup violence we have from the end of the Pleistocene and the beginning of the Holocene"

José Manuel Maíllo, prehistorian of the National University of Distance Education

The other major objection he makes to a study that he considers interesting is whether the cemetery is that of a war or was filled with successive attacks. “To demonstrate that it is an action extended in time, it is necessary to date a significant sample of human remains or graves. The radiometric dating carried out so far in the Jebel Sahaba necropolis are insufficient to support this hypothesis ”, Maíllo maintains. In fact, radiocarbon dating does not allow us to determine the exact date of death for each of those buried in cemetery 117.

As Maíllo recalls, “we have most of the empirical evidence on intergroup violence from the end of the Pleistocene and the beginning of the Holocene”.

Jebel Sahaba or Nataruk are examples of this type of violence between groups of hunter-gatherers.

The key could be that the two communities were no longer nomadic and had stable access to resources: "Both groups [were] semi-sedentary or sedentary and possibly with more delimited territories than the preceding groups."

You can follow MATERIA on

,

and

, or sign up here to receive

our weekly newsletter

.