The amber helped preserve the little lizard in great detail, with CT scans revealing its scales, skin, and soft tissue.

(CNN) -

A tiny 99-million-year-old skull buried in amber that became the subject of scientific debate last year was originally thought to belong to the world's smallest dinosaur species.

However, the high-profile scientific paper from March 2020 that revealed the Oculudentavis khaungraae discovery was withdrawn later that year.

New research published Monday, based on another specimen better preserved in amber, suggests that the skull was from a prehistoric lizard.

It's a really strange animal.

It doesn't look like any other lizard we have today, ”new study co-author Juan Diego Daza, a herpetologist and assistant professor of biological sciences at Sam Houston State University in Texas, said in a news release.

"We estimate that many lizards originated during this time, but their modern appearance had not yet evolved," he said.

That's why they can fool us.

They may have characteristics of this or that group, but in reality, they do not fit perfectly.

The authors of the new article published in the journal

Current Biology

named the creature Oculudentavis naga after the Naga people of India and Myanmar, where the amber was found.

They said it was from the same family or genus as Oculudentavis khaungraae, but probably from a different species.

Oculudentavis means "bird with fangs" in Latin, but Daza said the taxonomic rules for naming and organizing animal species meant they had to keep using it even if it wasn't exact.

advertising

"Since Oculudentavis is the name that was originally used to describe this taxon, it takes precedence and we must keep it," said Daxa.

"Taxonomy can sometimes be misleading."

The best-preserved amber, found in the same amber-mining region in Myanmar as the first described Oculudentavis specimen, contained part of the lizard's skeleton, including its skull, with visible scales and soft tissue.

Both pieces of amber were 99 million years old.

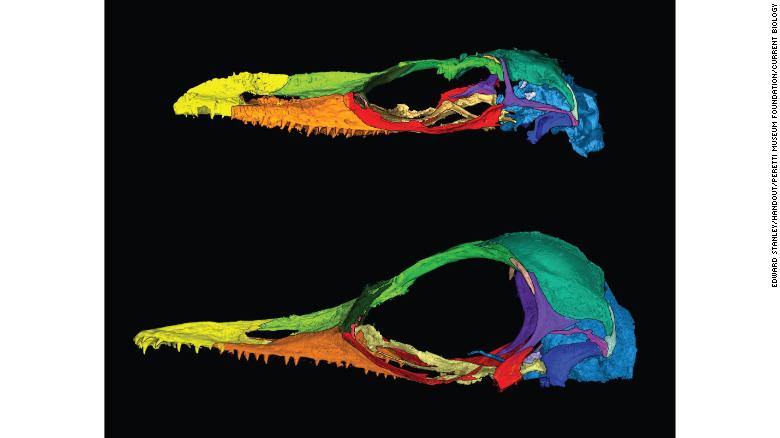

Oculudentavis naga, above, belongs to the same family as Oculudentavis khaungraae, below.

The skulls of both specimens were deformed during preservation, emphasizing lizard-like features in one and bird-like features in the other.

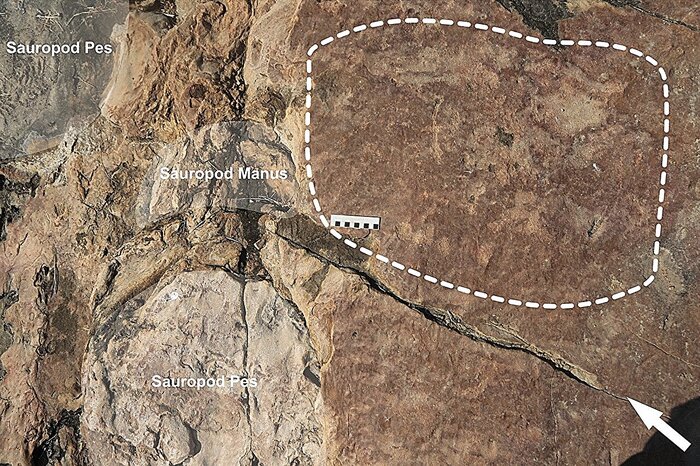

This dinosaur was the size of a basketball court

Distorted skulls

The authors said the creature was difficult to classify, but by using CT scans to separate, analyze and compare each bone from the two species, they detected characteristics that identified the animals as lizards.

These included the presence of scales;

teeth that are attached directly to the jawbone rather than fit into cavities, like dinosaur teeth;

lizard-like eye structures and shoulder bones;

and a hockey stick-shaped skull that is universally shared by other scaly reptiles.

In the best-preserved specimen, the team saw a raised ridge running down the top of the snout and a flap of loose skin under the chin that may have been inflated on display, characteristics shared by other lizards.

The authors believe that the skulls of both species had warped as the amber, made from resin balls of ancient tree bark, hardened around them.

They said that Oculudentavis khaungraae's snout was compressed into a narrower shape, more like a beak, while Oculudentavis naga's brain box was compressed.

The distortions increased bird characteristics on one skull and lizard characteristics on the other, said co-author Edward Stanley, director of the Laboratory of Digital Dissemination and Discovery at the Florida Museum of Natural History.

"Imagine picking up a lizard and pinching its nose into a triangular shape," Stanley said in a statement.

"It would be much more like a bird."

Birds are the only living relatives of dinosaurs.

Oculudentavis naga, depicted in this artist's print, is a strange lizard that research initially categorized as a small bird-like dinosaur.

An ethical minefield

Some of the most interesting finds in paleontology in recent years have emerged from the rich amber deposits of northern Myanmar.

Much of the amber reaches the markets of southwest China, where it is bought by collectors and scientists.

However, ethical concerns have arisen about who benefits from the sale of amber, particularly since 2017, when Myanmar's armed forces took control of the amber mines.

Government forces and ethnic minorities have fought in this region for years, and a United Nations report has accused the military of torture, kidnapping, rape and sexual violence.

The study authors said in the press release that the amber was purchased by gemologist Adolf Peretti before 2017 from a licensed company that has no ties to the Myanmar military, and that the money from the sale did not support the armed conflict.

They said the use of the specimen followed guidelines set by the Society for Vertebrate Paleontology, which has asked colleagues to refrain from working with amber sourced from Myanmar since June 2017.

A new Mexican dinosaur: look at Tlatolophus Galorum, discovered by paleontologists in Coahuila

“As scientists, we believe that it is our job to reveal these priceless vestiges of life, so that everyone can learn more about the past.

But we must be very careful that during the process, we do not benefit a group of people who commit crimes against humanity, "said Daza.

"In the end, the credit must go to the miners who risk their lives to recover these amazing amber fossils."

Dinosaur