The primitive appearance of elephants transports us to an ancient and idyllic world that has remained unchanged for millions of years. But these pachyderms are not the guardians of a world that came pristine to our ancestors, but only the survivors of the great collapse that their lineage, the Proboscideans, has suffered during the last three million years. To get an idea of the magnitude of the proboscidean decline, it is enough to make a simple comparison: today there are only three species of elephants (the African savanna elephant, the African forest elephant and the Asian elephant), and yet, thanks to the fossils we know that there were almost 200 species in the past (some emblematic like the mammoth, mastodons, deinoteria, etc.).

Only three million years ago - the Earth has more than 4,500 - more than 30 species of proboscideans lived on our planet, living in Africa and Asia, but also in Europe, North America and South America.

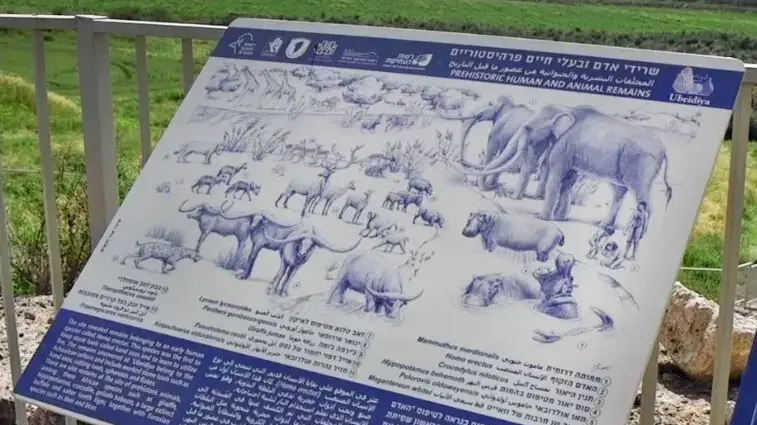

And, most surprisingly, it was not difficult to find sites where two or three species of these giants coexisted at the same time.

Some of our oldest ancestors, such as Australopithecus, came to witness this abundance.

Today, more than 98% of all that diversity has disappeared.

What happened?

"Most of the collapse of this group of majestic animals was due to environmental changes"

In a study we published today, we show that most of the collapse of this group of majestic animals was due to environmental changes.

With the expansion of the savannas and grasslands seven million years ago, the groups of proboscideans most suitable for life in wooded areas and with diets of fruits and shoots began their decline.

Meanwhile, the proboscidean species typical of open spaces, capable of feeding on less nutritious plant matter (grass and even wood), multiplied and spread throughout the planet.

A sample of the enormous diversity of forms that the proboscideans reached, including their different types of dentition.

From left to right, the species are ordered from oldest to most recent.Oscar Sanisidro

Around three million years ago, with the advent of the glaciations, everything changed again, since they caused very rapid environmental fluctuations and an unprecedented rate of extinction of many species of proboscis of all kinds. Did early Homo sapiens have anything to do with the final decline of the proboscideans? Everything indicates that humans were not the main responsible. We found that there was a last phase of sudden collapse, when species extinctions soared in Eurasia and America in the last 160,000 and 75,000 years respectively, before the arrival of Homo sapiens on these continents. However, we do not see such a rapid collapse in Africa where

Homo sapiens

they were present for tens of thousands of years.

Therefore, our conclusion is that environmental changes were the main responsible for the fall of the proboscideans, although hunting by our ancestors surely had a disastrous impact on the few species that survived until later times.

"It is in the early 70's when the idea arises that prehistoric humans had already led various species to extinction"

The find offers some interesting insights into understanding extinction processes beyond proboscideans. First, lineages can quickly disappear without ever having reached a phase of decline. The idea that lineages, like civilizations, have a phase of expansion and another of degeneration that precedes extinction was widespread among paleontologists in the second half of the 19th century. Thus the Darwinian notions were embedded that those that are extinguished are the primitive, imperfect, less suitable forms, replaced by better adapted forms through the struggle for resources. Thus extinction, which could only be the result of natural selection, played a role in clearing an abundant and constantly improving natural world.These ideas were in perfect harmony with the idiosyncrasies of the Victorian era, of great technical advances and insatiable exploitation of natural resources, and framed the subjugation and annihilation of indigenous peoples as the natural result of the encounter of an advanced society and the savages.

Curiously, the idea of progress in evolution is still deeply rooted in popular culture, in curricula, and in popular science.

However, three million years ago no one could have predicted the rapid collapse of the proboscideans, which were at the maximum of their diversity and had spread throughout the world.

No paleontologist who had traveled in time to that moment would have concluded that proboscideans were poorly adapted to their environments, forcing us to view extinction as a much more random phenomenon and largely triggered by unpredictable environmental changes. .

"The activities of our ancestors surely added to what was already a maelstrom of extinctions"

The 20th century brought new approaches to evolution. To begin with, the idea of a nature of infinite abundance faded. Beginning in the 1960s, paleontologists find incontestable evidence that the world is shaken by great mass extinctions. The development of ecology brought the idea of the interdependence of the elements of the natural world, the delicate balance of ecosystems, and the notion that our future well-being as a species went through preserving nature. It is in this new context, in the early 1970s, when the idea arises that prehistoric humans had already led various species to extinction as a result of overhunting.

This idea continues to fuel debate among scientists. It has been observed that in some regions the first records of human presence coincide with the last of some species of large mammals. But this evidence may also be compatible with the fact that the same climatic changes that facilitated the dispersal of some were the last straw for the others. Rather than focus on the extinctions of large mammals in the past 100,000 years, our work on proboscids offers a broader perspective for assessing the activities of prehistoric humans in the context of a changing world over millions of years. The activities of our ancestors surely added to what was already a maelstrom of extinctions in such a way that we will never know how many of them they were really responsible for.The debate is still open.

Juan López Cantalapiedra

is a researcher at the University of Alcalá and main author of the research,

published today in 'Nature Ecology & Evolution'

.

You can follow

MATERIA

on

,

and

, or sign up here to receive

our weekly newsletter

.

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/DXPUIGHRZZEKNMVHLDNKFJFAMY.jpg)

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/4RITWNCKAZFB3I3MBXYYKH6YDI.jpg)