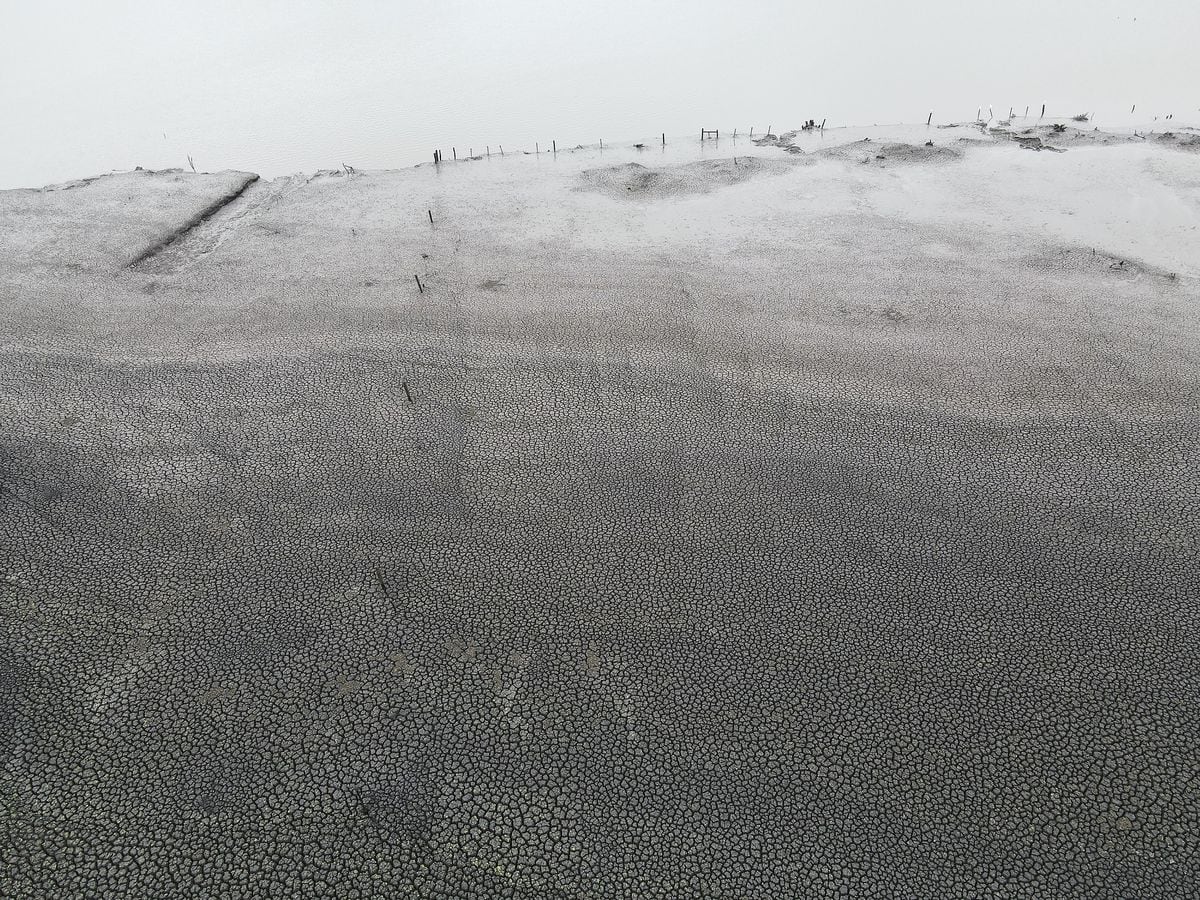

The waters of the Nile are increasing in temperature as the summer progresses, but, like last year, they are not doing so only due to the intense summer heat.

As in 2020, Ethiopia insists on its intention to continue with the second phase of filling the gigantic dam that it is completing on its section of the river, even more ambitious than the previous one, when the rainy season begins this July.

And this, despite the total lack of agreement on how to manage the process with Egypt and Sudan, the two countries downstream of the reservoir.

The critical moment for the onset of the rains has come not only with no signs of compromise in sight, but with the parties in an increasingly tense stalemate that some fear will increase instability in the region.

More information

Egypt condemns five young 'influencers' for 'immoral' videos

The body of the assassinated Spanish aid worker in Ethiopia transferred to Addis Ababa

Built on the main tributary of the Nile, the Blue Nile, which with other smaller watercourses provides 86% of the river's flow, the Renaissance Dam is set to be the largest hydroelectric dam in Africa and is already in a construction phase very advanced. When it is finished, it will have the capacity to hold 70,000 million cubic meters of water and the surface of the reservoir will be 247 square kilometers. The Ethiopian idea is to generate some 6,000 megawatts of electricity, which the Government of that country considers essential to power its industrialization projects. For Ethiopia, which estimates that the work will increase its power generating capacity by 115%, it is a key project for its development.

Egypt, whose water reserves depend on the water of the Nile for 98%, fears, however, that the reservoir fatally limits its access to this vital resource. Sudan, another riparian country, is concerned for its safety and the effect on its own water stations and dams. These two countries had traditionally assumed control over the flow of the Nile, by virtue of colonial agreements that Cairo and Khartoum tried to shield in a bilateral pact signed in 1959 to share the bulk of its waters.

The only glimmer of hope to break the blockade and move positions closer, after more than a decade of unsuccessful attempts to sign an agreement, came in April. Delegations from the three countries met in Kinshasa, the capital of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, in a meeting that Egypt saw as the last chance to reactivate negotiations before the rainy season in July. Three days were enough to bury the attempt, leaving the process once again stagnant and with hardly any common ground.

Since the resounding failure in Kinshasa, the parties seem doomed not to agree on anything.

Sudan and Egypt have proposed turning to the European Union, the United States and the UN, as well as the African Union, to mediate, something that Ethiopia sees as an attempt to move the negotiations outside the African framework - its preferred - at a time when that Addis Ababa's image in the international community has been damaged by the war in Tigray, according to an Ethiopian diplomatic source.

The parties do not even agree on whether the second phase of filling the dam has already started, as Khartoum is feared, or has not yet, as Addis Ababa argues, in a tangle reminiscent of last year.

Meanwhile, mistrust and tension have been mounting, especially between Sudan and Ethiopia. In addition to their divergence around the Renaissance dam, the temperature between the two has been rising in recent months as a result of the arrival of Ethiopian refugees from Tigray to Sudan, and, above all, due to a dispute in a border area, Al -Fashaga, in which sporadic military confrontations have been registered. A dangerous cocktail of three elements that many believe should be deactivated at the same time.

Egypt, for its part, has taken advantage of this escalation between Khartoum and Addis Ababa to strengthen its ties with Sudan and try to do the same in the rest of the region.

In this sense, in recent months Cairo and Khartoum have significantly expanded their economic, military and diplomatic cooperation, a harmony that is reflected in their coordinated management of the dam crisis, despite having very different interests and fears.

The most recent example of this has been its synchronized approach to the issue, last June, to the UN Security Council, which, however, shows little interest in intervening in this matter.

Rhetorical escalation

At the same time, these two countries have uncharacteristically raised their tone against Ethiopia, in a rhetorical escalation that has, however, been supported by an incoherent narrative. In March, Egyptian President Abdelfatá Al Sisi directly threatened Ethiopia for the first time, and Sudanese Irrigation Minister Yasser Abbas warned in April that "all options" are open. But in parallel, Sudan's Foreign Minister Mariam Al-Mahdi insists that Sudan will only opt for diplomatic channels, and her Egyptian counterpart, Sameh Shoukry, came to assure in May that the second phase of filling the dam Ethiopian is not even going to affect the water interests of his country.

In recent months, Egypt and Sudan have also signed two military cooperation agreements, and their Armed Forces have conducted two joint air exercises.

In March, in addition, they carried out other exercises, with the participation of their land, naval and air forces, called Guardians of the Nile, in what seems a clear message towards Ethiopia.

In parallel, Cairo has stepped up its diplomatic offensive in East Africa over the past year to try to counter Ethiopia's quest for regional power status.

Thus, senior officers, military and civilians, have visited several countries in the region and have received delegations at home to establish relationships at the highest level and strengthen ties, especially in defense matters.

Egypt has signed military and security agreements of various kinds since the beginning of the year with other countries of the Nile basin such as Uganda, Burundi and Kenya. And its Chief of Staff, Mohamed Farid Hegazy, one of the most active figures in this soft offensive in the region, has met and agreed to strengthen ties with his counterparts in Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

But despite these agreements, the reception that the Cairo initiative is having is less tangible. “This diplomatic offensive can work up to a point, where perhaps these states do not explicitly support Ethiopia or the position of [countries] upstream. But I don't think it means that when they have to make a decision about how to share the river's waters fairly, they take the Egyptian side, ”says William Davison, Ethiopia analyst and Nile basin expert at the International Crisis Group. In fact, the riparian countries with which Cairo has concluded agreements, have opposed in the past, like Ethiopia, the colonial pacts that gave control of the river flow to Egypt and Sudan.

In addition to its pulse with Ethiopia, Egypt's renewed initiative in East Africa also seeks to expand its influence and presence in the strategic Horn of Africa, a key region for maritime trade in the direction of its precious Suez Canal.

“For us, East Africa is not only about water resources, but is also interrelated with the security of the Red Sea, the Gulf, and the Bab El-Mandeb Strait to the Suez Canal, as well as the movement of international trade, of oil and gas, and even of the military fleets ”, slides Ambassador Mohamed Higazy, former adviser to the Egyptian Foreign Minister.

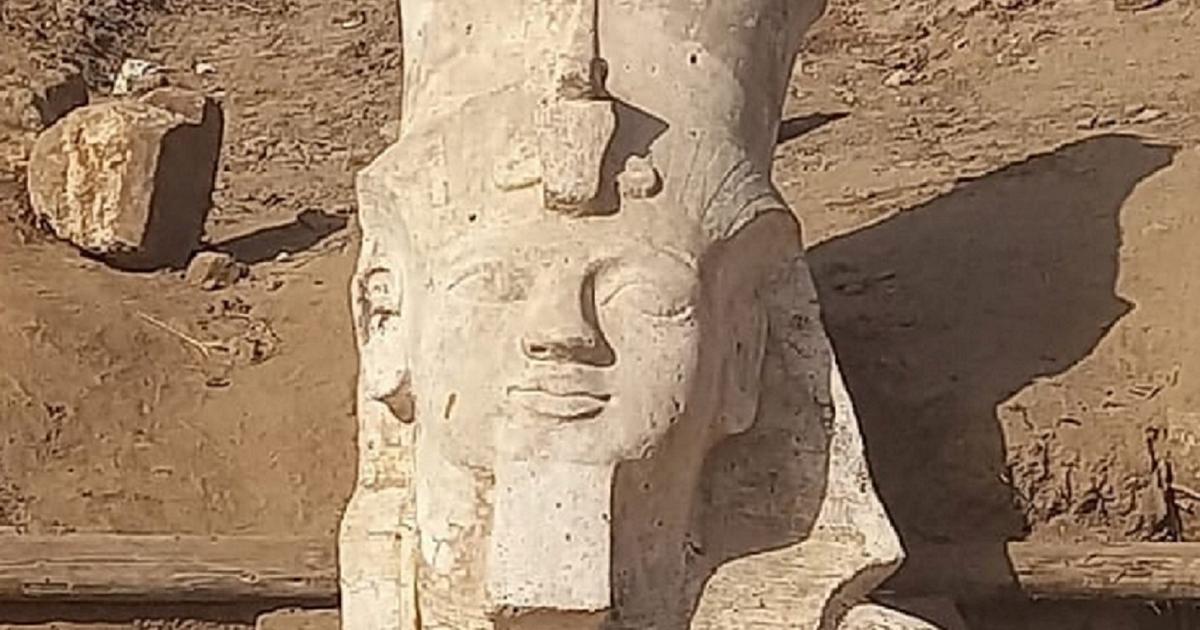

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/4FLE5PNY3VBLRCDNGWKQRJSUN4.jpg)

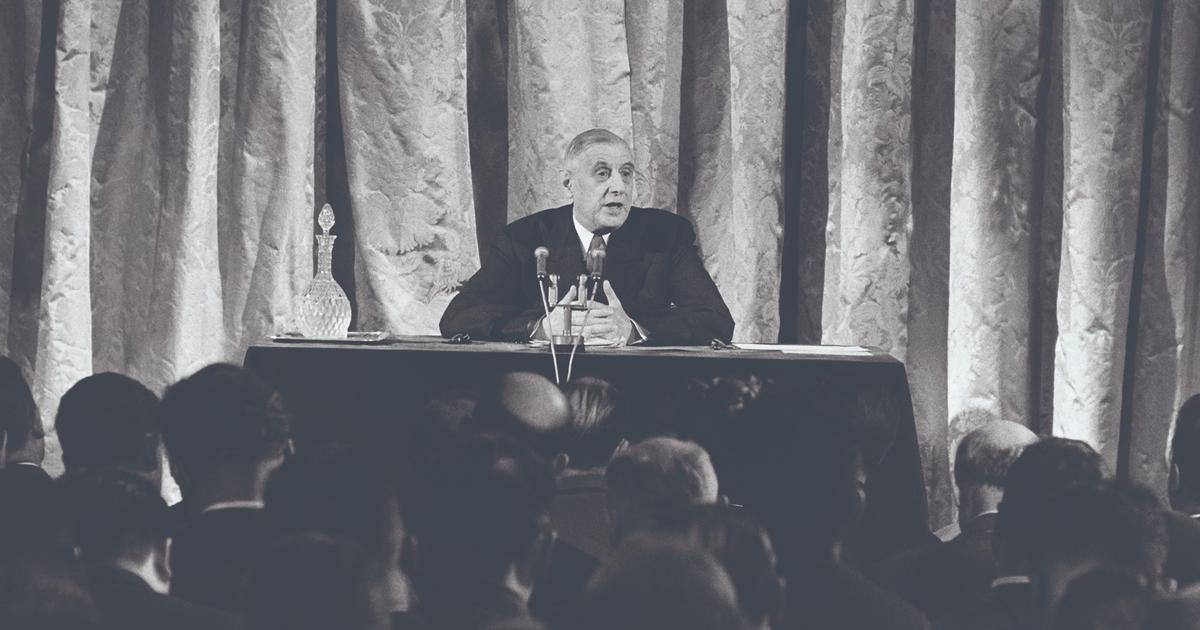

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/KMEYMJKESBAZBE4MRBAM4TGHIQ.jpg)