Editor's Note:

Celeste Olalquiaga is a cultural historian with a Ph.D. from Columbia University and the author of "Megalopolis" (1992) and "The Artificial Kingdom" (1998).

In 2013, he founded Proyecto Helicoide to draw attention to the modern ruin of Helicoide, in Caracas, Venezuela, a project that has produced exhibitions and fueled "The Downward Spiral: The Descent from Shopping Center to Helicoide Prison" (2018).

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author.

This note was originally published in 2019.

(CNN) -

The huge futuristic spiral known as the Helicoide has a reputation as the worst torture center in the country.

It has become a "dark place" where the different Venezuelan police forces have their headquarters, in particular the Sebin intelligence agency and the PNB (National Police).

Several inmates have reported abuse at the prison, which CNN has reported.

The immediacy and horror of this situation tend to hide a poignant structural condition that is the underlying cause of the socialist revolution led by the late Hugo Chávez and the political stalemate that afflicts Venezuela today.

El Helicoide is a microcosm of the contradictions written in the modern history of Venezuela.

A promise of instant "first world" development amid ever-expanding slums.

advertising

LEE: The poor and hungry will decide the future of Venezuela

The book "Downward Spiral: El Helicoide's Descent from Mall to Prison" (2018), which I edited with cultural historian Lisa Blackmore, presents the history of the building and its many failures and contradictions, along with archival photography and personal testimonies that attest to the original grandeur of the building and eventual collapse.

Originally conceived as a monumental showroom for the country's emerging oil and mineral industries, the Helicoide was built between 1956 and 1961 and would have been the largest and most modern shopping center in America.

It was built in the center-south of Caracas, on a rocky hill that was first leveled in seven levels in a helical or spiral way.

The sculpted hill was then poured onto concrete, creating two interlocking spirals with 4.02 kilometers of vehicle ramps where drivers could park in front of the stores of their choice.

The 60,000-square-meter structure would have housed 300 luxury stores, eight cinemas, a hotel and a helipad, among many other consumer amenities.

At a cost of $ 10 million (equivalent to $ 90 million today), the Helicoide would feature the technology of the time, including closed-circuit television and high-speed custom Austrian elevators that never made it out of their cases and they were finally looted.

Its geodesic dome, the first of those inspired by the famous Buckminster Fuller project to be installed outside the United States, was stored for 20 years before being assembled in one of the building's many failed reclamation projects.

The old commercial center is now the headquarters of the Bolivarian National Intelligence Service (SEBIN).

(Credit: JUAN BARRETO / AFP / AFP / Getty Images)

Aiming to become the symbol of an ultra-modern Caracas and a rapidly developing Venezuela, the daring size and shape of the Helicoide was widely admired: the structure stood out in the 1961 MoMa exhibition as a new form of architecture, with the Helicoide originally combining transportation with an exhibition and a shopping center, and appeared on the covers of major international magazines.

However, as photos of his striking models appeared around the world, the construction site in Caracas was coming to a halt. After the fall of the dictator Marcos Pérez Jiménez (1952-1958), the architects of the building, Jorge Romero Gutiérrez, Pedro Neuberger and Dirk Bornhorst, were suspected of having received financial aid from the military regime. Although never documented or proven, this claim was used by the incoming democratic government, which refused to guarantee the international credits necessary to finalize the structure.

A complicated dispute arose between the construction company, the store owners (a novel form of fundraising) and the state. Apparently, even Nelson Rockefeller, who had several businesses in Venezuela (including the Creole Petroleum Corporation, which for several years was the largest oil producer in the world), was interested in buying the Helicoide, but the bureaucracy made it impossible. The construction company went bankrupt and all work on the building ceased in 1961, a year before its completion. On the left, in the raw concrete, years of neglect followed. In 1975, the structure passed into the hands of the state.

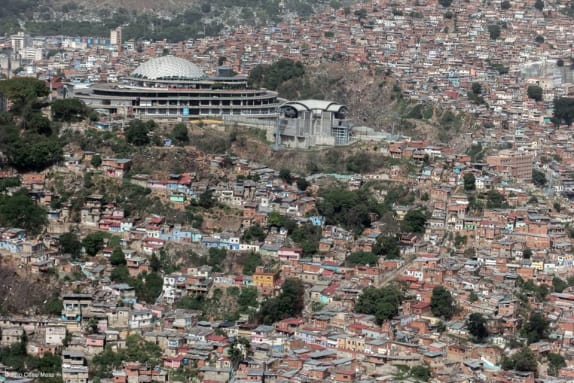

El Helicoide is surrounded by popular areas, known locally as neighborhoods, namely those of San Agustín del Sur. Like so many other neighborhoods that now account for more than half of the built environment in Caracas, this community began as shacks built by rural migrants in the mid-19th century, growing exponentially after the discovery of oil in 1918 and the industrial modernization of Caracas that began to late thirties.

The building's construction coincided with extensive state-led projects created to demolish such informal housing developments at the time, and it played a crucial role in urban planning for mid-century Caracas. As such, the futuristic 1950s form of the Helicoid embodied the dramatic contrast between an oil-driven modernization, designed to propel the country from a semi-feudal economy to a 20th-century industrial powerhouse, and the huge social inequalities in which this process was based. These disparities, which kept 80% of Venezuelans destitute, paved the way for Hugo Chávez's Bolivarian Revolution.

If this self-described socialism kept its promises, the inhabitants of the neighborhoods would have received adequate housing and living conditions. Instead, San Agustín del Sur is now considered one of the most dangerous slums in Caracas. Its residents have suffered through the different phases of the Helicoide, beginning when sections of the community were razed to make way for the building; continuing with the "Great Occupation" of 1979-1982, when 10,000 people remained in the building for three years in extreme conditions; and bearing a different kind of threat since 1985 once the intelligence police (then DISIP, now SEBIN) officially received a 15-year lease for the two lower levels of the building, where the prisoner cells are located.

Although it held political prisoners since the beginning of this latest occupation, Helicoide's role as a torture center and spiral jail became public after the massive protests of 2014 and 2017, when hundreds of students were illegally taken and held, some for months. and years.

Venezuelan authorities have long denied torture cases there.

For example, in May 2018, the attorney general of Venezuela, Tarek William Saab, speaking with CNN en Español, rejected the allegations of torture, extortion and the presence of minors in prison who were in the center.

The Helicoide was built in the 1950s. (Credit: Julio César Mesa, 2015. Courtesy of projecthelicoide.com)

This year, as Maduro's government has increasingly been cornered by the National Assembly and international powers declaring his second term illegitimate, government repression has been brutally focused on the neighborhoods of Caracas.

Its inhabitants, formerly the proud followers of a Bolivarian Revolution that gave them hope and dignity, have been the most affected by its failure.

Now they are fighting the official armed forces of a government that claims to protect them as it hits their communities with violent late-night attacks away from television cameras and social media.

Once hailed as the possible icon of Venezuela's accelerating modernity, the Helicoide's downward spiral sadly represents the collapse of a national dream built on unsustainable social divisions.

It can only be expected that both Venezuela and construction will rise up from their current situation and face the challenges of a country whose vast oil reserves still have unfulfilled potential.

For this to happen, justice must be done to the country's political prisoners, but also to its ever-present masses of urban poor.

ArchitectureCaracasCrisis in Venezuela