In January 2019, a tornado devastated several municipalities in Havana, mainly Regla and Diez de Octubre, and left seven dead, 10,000 displaced and some 8,000 homes affected. In addition, it provoked an unprecedented revolution in Cuba: for the first time, the island saw a civil mobilization driven by mobile data, activated by the Government only a month before that disaster. The availability of the Internet on cell phones made citizen solidarity with affected families greater than ever. For months people were taking donations to the affected neighborhoods. Accustomed to monopolizing all aid and fearing that this would be interpreted as a questioning of their abilities to deal with the catastrophe, the Government then wanted to be the intermediary between people in need and those who wanted to donate.But it was impossible for him to monopolize solidarity.

Cubans living inside and outside of Cuba understood very quickly that the Internet could be an extraordinary ally to conquer some freedom in an authoritarian context. The mobilization of the tornado was followed by a march against animal abuse, in April 2019, and a few weeks later, another in defense of the rights of the LGBTIQ community, the first called by independent organizations. But the second did not have government authorization and was strongly repressed. Then came the viral challenges: there was the

#Trashtag challenge,

that mobilized environmental groups to clean coasts, rivers and forests, and #LaColaChallenge, a call to publish photos and reports of the massive lines to buy food, hygiene products and other basic goods on social networks. The Cuban version of Fridays For Future, the global environmental mobilization of young people, also arrived, but on the island they did not receive permission to demonstrate in public spaces. The problem was not so much in the ideals of the convocation as in the fact that the population organized itself independently of the State.

Independent media and opposition groups also found a space on the Internet and cell phones to spread their ideas. Without them, the impact of the San Isidro Movement or the viralization of the song

Patria y Vida

,

the dissident anthem

,

would not have been so great

that turned around an old official slogan ('Homeland or Death') and that irritated the regime. The government also quickly realized the effect mobile data could have. As citizens became empowered with digital tools, repression adapted to the new circumstances. Over time, fines for publications on social networks came, mainly to independent activists and journalists, website blocks, Internet and mobile data cuts in critical places or moments, and even persecution and arrests. On July 11, several of the best known dissident figures had been without access to mobile data for several days and with police surveillance outside their homes to prevent their departure.

View of a graffiti with the word "courage", on a street in Havana, Cuba, this Tuesday, July 20, 2021Ernesto Mastrascusa / EFE

But society jumped all those barriers. When the residents of San Antonio de los Baños, southwest of Havana, took to the streets in the largest protest against the Cuban Government since the 1990s, the citizens who demonstrated shouting "We want freedom" were not following a previous call of any dissident group, nor were they under surveillance. They were anonymous and diverse people pushed by deep shortages exacerbated by the coronavirus pandemic. And it was not a small group. When the Government cut the Internet service, it was too late: the videos of the rebellion had gone viral and inspired many people who yearned for changes throughout the national territory. According to the records of Inventario, an independent project specialized in data journalism,there were protests in more than 90 parts of the country that day alone.

The protesters' tools on July 11 were mainly two: live broadcasts through Facebook Live and

hashtags

, the labels that allow information to be grouped on social networks. Broadcasting a direct is popularly known on the island as "doing a direct". Accustomed to censorship, Cubans know that these live videos are more difficult to eliminate and that is why it is one of their most powerful reporting weapons. The direct from San Antonio was adding followers, views and outrage. Then the

hashtags

followed

. The hashtags #SOSCuba, #SOSMatanzas and #PatriaYVida lit up on platforms like Twitter. And not by chance. Behind each of them are stories, contexts and strategies.

For example, the tag beginning with "SOS" is very popular in Latin America. It has been used on multiple occasions in the demonstrations against the Nicolás Maduro regime in Venezuela, in Nicaragua to document the excesses of Daniel Ortega, and recently it has been used in the same way in the massive protests in Colombia. According to estimates by the AFP agency, between July 5 and 8, some 5,000 tweets were published with the hashtag #SOSCuba. On July 9, around 100,000; on July 11, 1.5 million; and the 12th, two million. Meanwhile, the #PatriaYVida label, alluding to the song by rappers Maykel Osorbo and El Funky, who live on the island, along with other Cuban musicians who live abroad, went viral in the same way as their video clip, which in less In a week, he added more than one and a half million views on YouTube.Today it represents a slogan for those who disagree with the system and was one of the most chanted phrases in the demonstrations.

The government blames a hashtag

From Twitter, the mobilization jumped to three instant messaging networks: WhatsApp, Signal and Telegram.

In his book

Cuba's Digital Revolution

(

The digital revolution in Cuba

), published in June, Ted Henken reveals that Facebook is the most important network in the country, but that Cubans also use WhatsApp, Signal and Telegram to a large extent.

Twitter and Instagram are much less popular on the island, but they play an important role in multiplying trends abroad.

In addition, thanks to social networks, the protesters documented with testimonies and videos how massive the protests were, the repression by the authorities and the subsequent arrests in their homes of those who participated in them.

In total, more than 500 people deprived of liberty and missing have been reported.

Nine of them are minors.

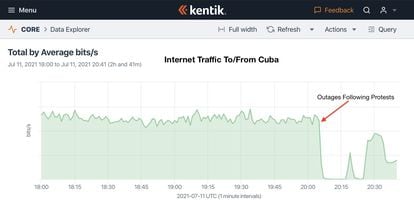

Graphic from internet monitoring company Kentik showing network blockage in Cuba on July 11.

On July 11, almost everything was documented until, around four in the afternoon, the connection stopped working. NetBlocks, an Internet monitoring site, reported that the network had been restricted and that the most affected platforms were WhatsApp, Facebook, Instagram and Telegram. A report published by that company on July 12 revealed that the blockade had “a similar pattern to the restrictions on social networks” that were seen during the November 27 protest in front of the Ministry of Culture in Havana, in solidarity with the San Isidro Movement and in defense of artistic and expression freedom.

"Large Internet outages are very rare, but they usually happen in Cuba," reads a report by the Internet monitoring company Kentik, which on July 11 documented the blockade and a "targeted censorship" of Signal, Telegram and WhatsApp. Seven hours after the protests began, the direct protests ended and the streets were controlled by the police, elite army forces and groups of civilians armed with sticks and stones who responded to the "order to fight to defend the revolution" of President Miguel Díaz Canel on national television. The government thus tried to spread confusion and misinformation, but it was too late. The

hashtags

kept moving around the world.

Cuban-Americans demonstrate in front of the White House on July 17 with the slogan of the protests # SOSCuba.WILL OLIVER / EFE

In the official version, the blame for the protests was largely the United States Government and social media. The Minister of Foreign Affairs, Bruno Rodríguez, affirmed in a press conference, two days after the mobilizations, that there was not a social outbreak, but a series of "riots" and "disorders on a very limited scale", in which “agents of a foreign power” and “criminal elements with criminal records” participated. And he denounced that "the incidents" were not only the result of Washington's policy towards Cuba, but of a "political communication operation" that was exacerbated with the launch of "the call for #SOSCuba in New York" in front of the United Nations headquarters. United. According to his hypothesis,That label came from a US company registered in Florida and the strategy was developed "on the very expensive servers of US companies, which protect these digital operations against Cuba for political purposes."

He also said that if the hashtag #SOSCuba became a global trend it was due to "an inorganic action from North American territory" supported by robots, fake accounts, digital media and activists. "It is an aggression by the United States Government, which today does not need missiles, does not need Marines, and which has an enormous capacity for non-conventional warfare in a computerized way," said the Chancellor. However, the label was born earlier than the minister claimed. On the Twitter account of the San Isidro Movement, for example, there are tweets with her from the end of April that denounce the police siege that dissident artist Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara faced then.

Later, it continued to be used to ask for solidarity with prisoners of conscience and it was not until July that its use was popularized to promote the creation of a humanitarian corridor that would facilitate the shipment of food and medicine to the island by Cubans living abroad.

In fact, it was various artists such as Daddy Yankee, Becky G, Natti Natasha, René Pérez (Resident), Alejandro Sanz, J Balvin, Nicky Jam or Mia Khalifa who made the public discussion about the health crisis in Cuba gain strength in the virtual space when making publications accompanied by #SOSCuba.

A window to the democratization of the island

It is not surprising that one of the government's responses to the protests was to block the Internet, a service that in Cuba is under the state monopoly of the Cuban Telecommunications Company (ETECSA). According to government figures shared by the organization Humans Rights Watch, 4.2 million of the 11.2 million residents in the country "are connected to the Internet through their mobiles." In addition, only 189,000 Cubans have Internet access in their residences, a figure that represents less than 5% of the population. Three years ago, they were even less privileged, since the service is not available to anyone who wishes to hire it, but to those who reside in specific areas that the company has selected.

December 2018 was a key date for Cuban history.

It was then that ETECSA activated the mobile data Internet connection service and for the first time civil society knew what it was like to be able to browse at any time and with privacy.

Before, most had to go to public spaces, parks almost always, and connect to an overloaded, slow and expensive Wi-Fi network.

That also meant that everyone was listening to the conversations of the person making video calls and that it was almost impossible to find a free bank, so users used to navigate sitting on the ground, in a container, in the grass or wherever they could.

Three girls use their mobile in Havana on July 14, 2021.YAMIL LAGE / AFP

The activation of mobile data drastically transformed Cuban society. In some ways, it became more democratic. Employment opportunities, sources of income,

influencers

multiplied

. The discourses and narratives about the Cuban reality diversified. Anyone could post a complaint or express their opinions on different topics. And that reality of the networks took a leap to the streets on July 11.

After the Internet shutdown that day, the service remains irregular and the Cubans who can have opted for alternatives. One of them in Psiphon, which allows them to browse social networks and messaging applications, such as WhatsApp and Telegram, through a VPN without the need for a connection to ETECSA. Meanwhile, the United States has already begun to consider the possibility of supporting the island with the connections. President Joe Biden himself pointed out that his government is evaluating whether it has the technological capacity to offer free Internet for Cuba in the face of the cut-off of mobile data, while Florida Senator Marco Rubio, of Cuban origin, has asked that the so-called "balloons of the Internet ”to provide free service to protesters.

And while the inhabitants of the island are kept in their homes in the face of the militarization of the streets, the emigrants and exiles have taken over with demonstrations in different cities of the world and continue to move the #SOSCuba label. But neither the trends in social networks nor the robots that the Chancellor spoke of would have managed to mobilize thousands of people in a country where protesting can land you in jail if there were no strong enough reasons for it. Surely those who make decisions on the island also know it. It is no coincidence that, three days after the protests, the Government announced new measures: exceptionally authorize the importation of food, cleaning products and medicines without limit and free of payment of tariffs until December 31, 2021.If the unpublished protest of July 11 has made one thing clear, it is that a decades-long exhaustion can hardly be neutralized by restricting digital rights.

Subscribe here to the

EL PAÍS América

newsletter

and receive all the informative keys of the current situation in the region.

You can also follow EL PAÍS TECNOLOGÍA on Facebook and Twitter or sign up here to receive the weekly newsletter.