The Mexican historian Martín Ríos Saloma (Mexico City, 45 years old) has spent several years trying to understand what the world was like - political, social, but also psychological - of the Spanish conquerors who arrived more than 500 years ago in what is now Mexico. To understand them, the UNAM researcher studied his doctorate at the Complutense University of Madrid, but little by little his academic project not only allowed him to know deeply what was happening in the kingdom of Castile before 1492, but also how the Spanish identity is then transformed in relation to the American territories. "America cannot be understood without Spain, but Spain cannot be understood without America either," he wrote in a 2019 column.

Ríos Saloma has just published a new book entitled

Conquistas

(Sílex) with essays by the best Mexican and Spanish historians about what happened 500 years ago, when the Mexica empire fell, a date that is commemorated next Friday, August 13.

EL PAÍS interviewed him.

Question.

The introduction to his new book says that it is important not to speak of 'The Conquest', but of 'The Conquests', in the plural.

Why is this plural so important?

Answer.

Because the new perspectives that we have been building among all - people like Federico Navarrete or Matthew Restall - we are very aware that it was not a single event and above all, that August 13, 1521, although it is a very important date In this process of conquest, in reality it only closes a first moment of military conquest and opens other horizons, other phases of the conquest of Mesoamerican territory.

In my specific case, I am concerned that people continue to focus solely on the military aspects of that exchange. As a medievalist –I was trained in Madrid and I have studied a lot the advance of the Reconquest, for example, or the construction of that Christian identity– I would like to convey through the book that the conquest is not only the military phase. There are also other types of linguistic, spiritual, religious, cultural, political conquests, in which there are two actors: those who arrive and those who come into contact with these exogenous groups. Mutually they feed and feed each other. It seems to me that the plural had an epistemological content. It is about changing the keys to reading our past and showing the plurality, richness, and complexity of a process of which we still do not know many aspects.

Q.

And what is your opinion regarding the debate in Mexico about not talking about 'the conquest' but about an 'invasion' or a 'rebellion'?

R.

It is an interesting debate because I think it tells us about the importance of this past event in the present.

There is a group of colleagues who have spoken of 'invasion', such as [historians] Pedro Salmerón or the recently deceased Luis Fernando Granados, and certainly, if we place ourselves in the sandals of those original inhabitants, it was an invasion.

But it is also true that this invasion was due to a series of pacts and agreements between some original inhabitants and the Castilians.

Those pacts and agreements were only possible thanks to mutually recognizing each other as equals.

It is also true that the

Ēxcān Tlahtōlōyān

, the famous Triple Alliance [of the Mexica], exercised a system of domination over multiple peoples.

Those subjugated peoples found in the Castilian armies, in the Castilian hosts, powerful allies that were going to allow them to configure new systems of power.

The term conquest has a Roman heritage, it is linked to Roman law.

Therefore, when one poses the military subjugation of a people as a 'conquest', deep down one is referring to the law, and converts its conquest into a legitimate process.

When you talk about 'invasion', even if it is the same military fact, you are taking away all legitimacy, because you are going to steal land or property from other people.

Cortés did indeed carry out a 'conquest'. The peoples subjected to the Mexica that they allied with Cortés clearly carry out a 'rebellion'. And indeed the Mexica lived this military process as an 'invasion'. It is not that one thing excludes the other. The problem has been that in the 20th and 21st centuries, different political affiliations have wanted to play with that past. But they are problems of the present, not necessarily of the past. Because even the bulk of the indigenous groups that actively participated [in the fall of Tenochtitlan], such as the Tlaxcalans, defined themselves as 'conquering Indians'. They were looking for, from that self-definition, a series of rights and privileges on the part of the crown. So the Tlaxcalans are neither traitors, nor are they victims, nor are they defeated. They are fully conquerors.

Oil of The Conquest of Mexico by anonymous author, in which Hernán Cortés orders the burning and destruction of idols, made between 1676 and 1700. Getty Images

Q.

In your essay, you say that it is important to understand how the political culture of the kingdom of Castile was formed in order to understand what happened in what is now Mexico.

Why should we care?

R.

Basically because the political culture that was configured throughout the late Castilian Middle Ages outlined the way in which the Hispanic monarchy was built from the sixteenth century: a monarchy made up of different kingdoms, and as a pact between the monarchy and the society as a whole. In the Middle Ages, society as a whole was the nobility and the Church. What the Catholic Monarchs particularly achieved was to convert the uses and privileges that the nobility had for their own benefit into actions for the benefit of the Crown. What the Crown, that is, the Queen, achieved was to subdue the nobility and convince them of the need to carry out actions in the service of the monarchy, in the service of the King. If we do not know what happens in Castile in the 15th century,We cannot understand how the writings of Hernán Cortés are articulated to legitimize his own actions before the Hispanic authorities. That's why they are so important

Cortés's

letters of relationship

, because he presents them as a service to the monarchy.

What Cortés manages to do is use the political culture and political language of his time to present his conquest actions as a service to the King.

Second, because it allows us to recover that idea of the pact in the construction of political alliances [in America].

There, Ms. Marina [also known as Malintzin] will play a fundamental role, not only as a linguistic translator for Cortés, but also as a cultural mediator.

He was able to do so because Cortés understands that only through negotiation can the construction of a new political pact be achieved.

As in the case of Medieval Castile, these alliances are sealed through marriages, mixed marriages between daughters of the indigenous nobility and Castilian soldiers.

Q.

That of making political alliances to conquer through marriage is forged just before 1492?

A.

Indeed, if the Catholic Monarchs do something, it is to forge a dynastic alliance with the marriage of Isabel and Fernando. They are two people who represent two different branches, but from the same family - they are cousins of the third degree or second degree - so they have to even falsify the papal dispensation at first in order to get married. Later the Pope already grants the royal bull. But the marriage of the Catholic Monarchs is nothing more than a political alliance of the dynasty sealed through marriage. What the Catholic Monarchs are going to do with their daughters is to weave alliances on a continental level with a single objective of isolating France, which is the great enemy of the moment. And what happens on the continent is replicated here in America.

Q.

And how did the Reconquest against the Kingdom of Granada and against Islam transform the experience of colonization in Tenochtitlan?

R.

The military experience there, for example, is very important, and we could refer to the 11th century with the conquest of Toledo in 1085 by King Alfonso VI. It was the first really important city to be conquered through a siege. From there, a geographical, political, cultural, religious, economic border is established between Christianity –that is, the Spanish-Christian kingdoms– and Islam. And that border remained practically until the first half of the 13th century, when King Ferdinand III conquered two very important cities: in 1236, the city of Córdoba, and in 1248 the city of Seville, a city that has an important hydric geography. A military experience of the war of sieges accumulates, where the important thing is not to destroy the city,rather, the city surrenders as soon as possible through pact and negotiation. In order to force the Muslim city to surrender, what there is is a siege: to surround the city to prevent it from receiving supplies and basically surrendering out of hunger. The idea that is on everyone's head is that these people surrender as soon as possible, because a siege is ultimately costly for both sides. Hernán Cortés was born within the framework of that war in Granada, and although he was too young to participate actively, he brings that military baggage that later began in the case of the conquest of Mesoamerica.The idea that is on everyone's head is that these people surrender as soon as possible, because a siege is ultimately costly for both sides. Hernán Cortés was born within the framework of that war in Granada, and although he was too young to participate actively, he brings that military baggage that later began in the case of the conquest of Mesoamerica.The idea that is on everyone's head is that these people surrender as soon as possible, because a siege is ultimately costly for both sides. Hernán Cortés was born within the framework of that war in Granada, and although he was too young to participate actively, he brings that military baggage that later began in the case of the conquest of Mesoamerica.

When one later reads Cortés and Bernal del Castillo's descriptions [of the fall of Tenochtitlan], we are reading a reproduction of that war of sieges: first, cutting off the city's water supply (the aqueducts, the fountains); second, to surround the city with the brigs (boats) to prevent the towns from receiving supplies; third, to bombard the city's defenses; and fourth, that the inhabitants of Tenochtitlan surrendered due to hunger. And that's it, the idea was that in three weeks Tenochtitlan would surrender. What Hernán Cortés never understood - because he could not understand it, because it was not his symbolic universe - was that for the Mexica Tenochtitlan was the center of the universe, the center of the cosmos. So they weren't going to give up so easily.

Q.

You have a phrase that says "America cannot be understood without Spain, but Spain cannot be understood without America either."

As a Mexican who has studied the conquest from Madrid, how do you see what happened in Spain is understood?

R.

Yes, I did my doctorate in Madrid, I lived there for six years, I have great friends there, and even before the pandemic I had the opportunity to travel at least once a year. I say this because it allowed me to verify the influence that the American continent has on Spanish culture. Beyond the linguistic differences that we have - differences in accent or words - there is a common cultural substrate. The historical problem is that, in general, Spain has seen itself as the country that brings civilization to America, the country that brings culture to America, and has been reluctant or has not had the necessary sensitivity to also recognize what America contributed. And it does not have it for many factors. To begin with, the construction of a national discourse in the 19th century that highlights its differences with respect to America.And of course some economic and cultural policies already very early in the twentieth century.

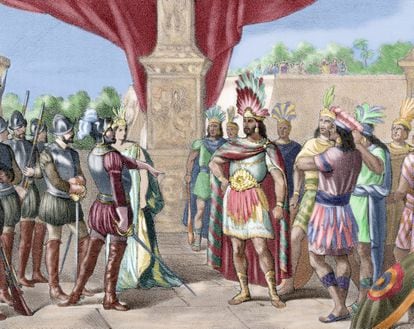

Color engraving from 1875 that represents the moment in which Hernán Cortés takes Moctezuma II prisoner, by an anonymous author. Getty Images

But America had a profound influence on the formation of that monarchy, which was composed and polycentric. It took a lot of things, like words. For example, the word 'canoe' is an Antillean word, and it is one of the first to be spread throughout the old world. From Nahuatl he took the word 'tizalt' which is the word 'chalk'. If we go to the culinary aspects, they have a wonderful potato omelette in any house, and everyone prides themselves on making the best potato omelette. What would that Spanish gastronomy be if it weren't for this potato omelette? [the potato is native to America]. Or the chocolate? From the avocado? From the tomato? They are everyday products, but we are no longer aware of their importance. One might also think that there are practically not many Native American names in the list of Spanish names,and that's true. But there were indeed a series of descendants of the great indigenous lineages that ended up living in the Castilian court, such as the counts of Moctezuma, to begin with. And then something that is obvious but we cannot forget: America was the recipient for three centuries of an immense number of inhabitants of the peninsula. And if we go to the 19th century, the great Spanish capitals were formed in Mexico. Banco Santander, which is so important today, was formed with capital produced by the Mexican economy.America was the recipient for three centuries of an immense number of inhabitants of the peninsula. And if we go to the 19th century, the great Spanish capitals were formed in Mexico. Banco Santander, which is so important today, was formed with capital produced by the Mexican economy.America was the recipient for three centuries of an immense number of inhabitants of the peninsula. And if we go to the 19th century, the great Spanish capitals were formed in Mexico. Banco Santander, which is so important today, was formed with capital produced by the Mexican economy.

So that's where I say that Spain cannot be understood without America, like a mirror in which one looks daily.

They build their identity, sometimes even in opposition, to America.

Well, ultimately America is working as a mirror and they need us to recognize themselves in that difference.

Q.

What do you think of the request for forgiveness that President López Obrador made to Spain?

R.

They asked me the same question two years ago and I said 'well, there is no need, it was another context, it was another country'. But today ... not that I disdain what I said two years ago. But I do believe that we must make more complex from a historical perspective what the President of the Republic is looking for. Just as we were all surprised by the request for a pardon, I was also surprised - and not pleasantly - by the virulence of the reaction in Spain. And the disqualification that has been made in various Spanish media. And particularly by people more closely linked to the right. When you hear from the world of culture this viceral reaction,why? And it seems to me that what the letter from the President of the Republic put was to put back into play a series of ideas about our national and collective identities that we have not resolved either in Mexico or in Spain.

In the notes published by the newspaper EL PAÍS in those days, everything was heard, there were five opinions that said exactly the opposite. Pérez-Reverte said that he did not have to ask for forgiveness, because it was other Spaniards, and that ultimately it was the Mexicans who had to ask for forgiveness. The one who was spokesman for Congress said no, that of course Spain brought civilization there and wiped out a barbarous tribe. Those of Podemos said yes, how good that they asked for forgiveness. Others said that the King of Spain had nothing to do with Felipe II or Carlos V.

Let's see, I wonder, from a historical perspective of the Spanish monarchy, regardless of who currently occupies the throne, it has been legitimized from the continuity of the family, from the dynastic continuity. From a historical and political perspective there has been no rupture, even though there are two different dynasties between the Habsburgs and the Bourbons. But then, for some things it was the same ruling family and for others not?

Today I could answer this question that the letter from President López Obrador deserves a moment of reflection and not disqualification for all of us.

To rethink what it is that both nations are at stake in the present, and see the enormous ignorance that exists within the inhabitants of both countries.

It seems to me that the president's letter is a golden occasion since it opens so many debates so that the professional sectors can get closer to society and show this richness of this shared history, which is not only made up of military historical events, but also of links affective, family ties, cultural ties, economic ties, simple ties.

Subscribe here

to the

newsletter

of EL PAÍS México and receive all the informative keys of the current situation of this country

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/L6TCOQ5HGZCWTOW6YNBMMGDKBA.jpg)