Priyanka runwal

08/18/2021 4:44 PM

Clarín.com

The New York Times International Weekly

Updated 08/18/2021 4:45 PM

Brain tissue is by nature soft.

Unlike bones, valves, or teeth, it is rich in fat and rots quickly, so it rarely appears in the

fossil record.

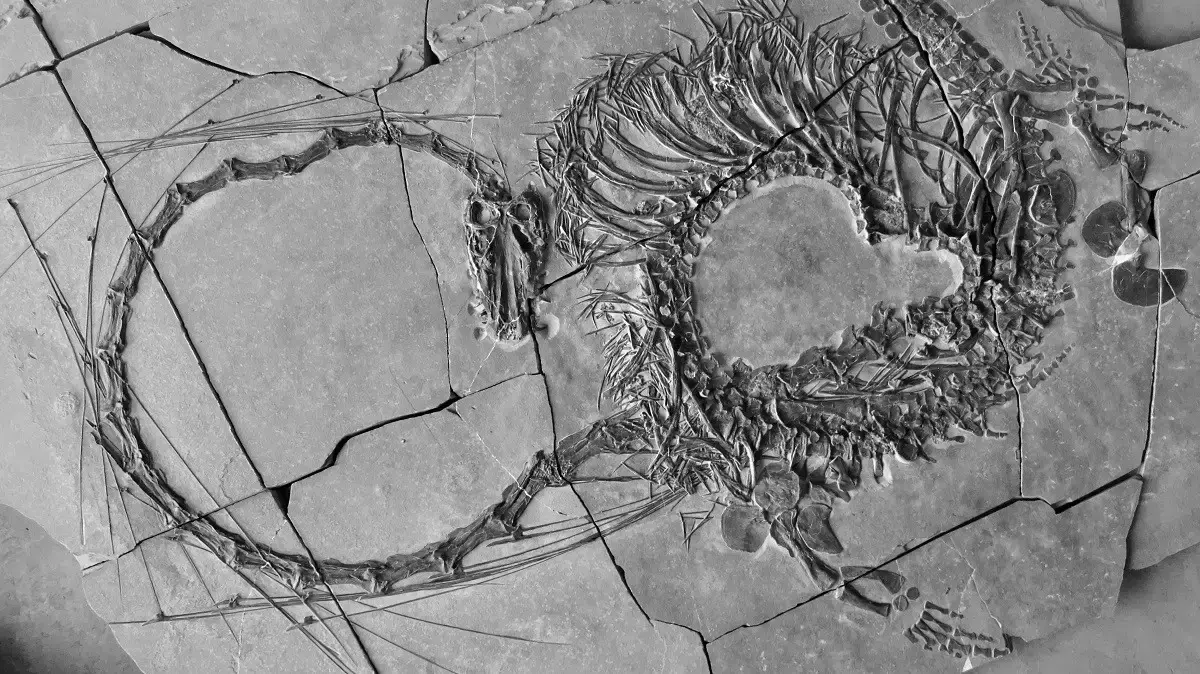

So when Russell Bicknell, a paleontologist specializing in invertebrates at the University of New England (Australia), observed that on the front of the body of a fossilized horseshoe crab there was

a white

spot where the animal's brain was located, was surprised.

Close-up of the brain, the first fossilized horseshoe crab brain ever found.

Photo Russell Bicknell.

A closer look revealed a rare imprint of the brain along with

other bits

of the creature's

nervous system

.

Unearthed from the Mazon Creek site in northeastern Illinois, and dating back

310 million years

, it is the first fossilized horseshoe crab brain ever found.

Dr. Bicknell and his colleagues reported the find last month in the journal

Geology.

"These kinds of fossils are so rare that if you stumble upon one, you are usually shocked," he said.

"We are talking about a level of wonder like that of

a needle in a haystack

."

The finding helps fill a gap in the evolution of arthropod brains and also shows

how little they have changed

over hundreds of millions of years.

Other Findings

Soft tissue preservation requires special conditions.

Scientists have found brains encased in fossilized tree resin, better known as

amber

, less than 66 million years old.

They have also found preserved brains as flattened films of carbon, sometimes replaced or overlaid by minerals in shale deposits more than 500 million years old.

These deposits include oceanic arthropod carcasses that sank to the seafloor, quickly became buried in the mud, and remained protected from immediate decomposition in the low-oxygen environment.

However, the fossilized brain of Euproops danae, which is preserved in a collection at

the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History

, required a number of different conditions to be preserved.

This arthropod was not a crab, but is closely related to spiders and scorpions.

Preservation

The extinct penny-sized horseshoe crab was buried more than 300 million years ago in what was a shallow, brackish sea basin.

The

siderite

, an iron carbonate mineral, rapidly accumulated around the dead creature's body, forming

a mold.

Over time, as soft tissue decomposed, a white clay mineral called

kaolinite

filled the void left by the brain.

It was this white cast on a dark gray rock that helped Dr. Bicknell detect the exceptionally preserved brain impression.

"This is a completely different mode of brain preservation," said Nicholas Strausfeld, a neuroanatomist at the University of Arizona who was one of the first to report a fossilized arthropod brain in 2012, but was not involved in this study.

"It is notable".

The brain of the extinct

Euproops

showed a central cavity for the passage of a feeding tube and branching nerves that would connect with the eyes and legs of the animal.

Dr. Bicknell and his colleagues compared this ancient brain structure to that of

Limulus polyphemus

, a species of horseshoe crab still found on the Atlantic coast, and found a striking similarity.

Although horseshoe crabs look somewhat different on the outside, the

internal architecture of

the brain had not really changed despite being separated by more than

300 million years.

"It is as if a set of motherboards has remained constant over geological time, while the

peripheral circuits

have been modified in various ways," said Dr. Strausfeld.

Although the E. danae fossil has been examined in the past by other researchers for its shape and dimensions, the brain, which is smaller than

a grain of rice

, went unnoticed.

"If you're not looking for that particular feature, then you're not going to see it," Dr. Bicknell said.

"You develop a search image in your head."

With the fortunate discovery of this well-preserved ancient brain, researchers hope to find more examples in other fossils from the Mazon Creek site.

"If there is one, there

has to be more,

" said Javier Ortega-Hernández, an invertebrate paleontologist at the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard University and a co-author of the study.

c.2021 The New York Times Company

Look also

With their fangs they rebuild the life of a woolly mammoth

How to rescue a famous extinct blue butterfly