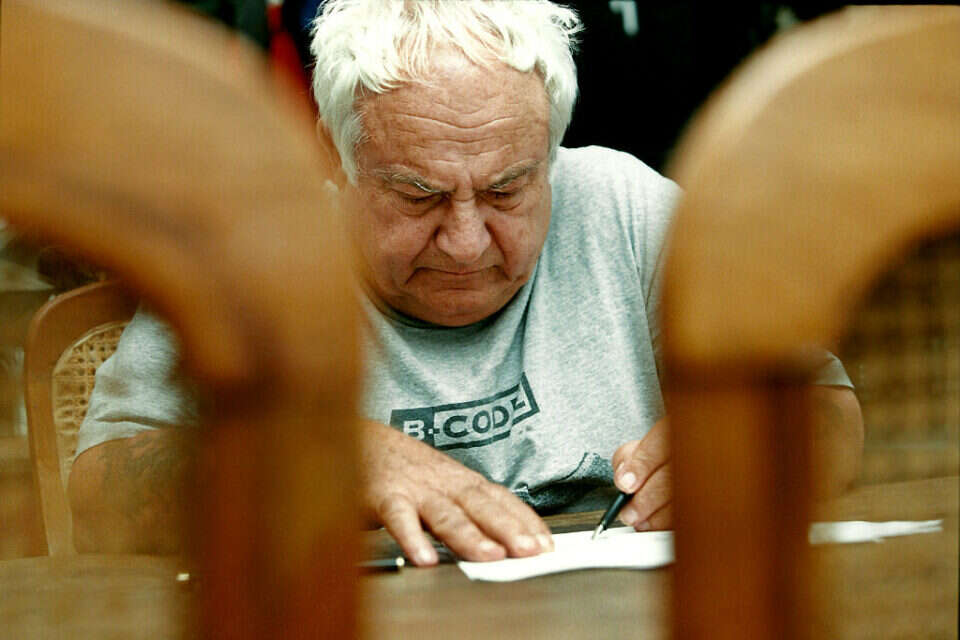

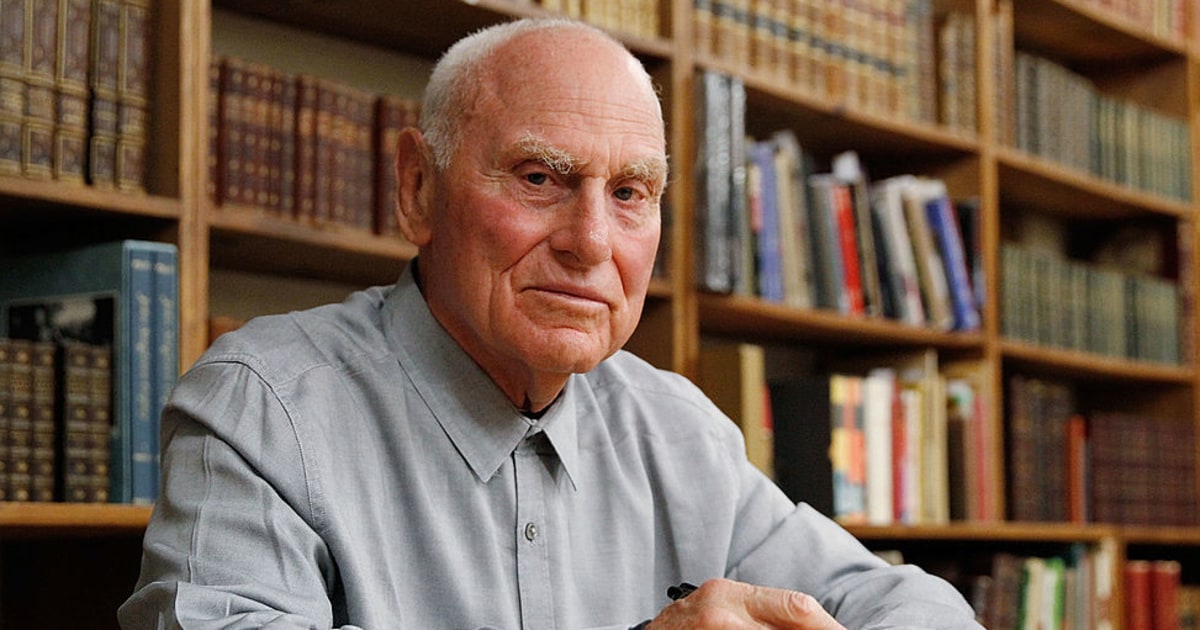

A few days ago, the sculptor Yigal Tumarkin died.

His original name was Peter Martin Gregor Heinrich Halberg, and he was born in Germany in 1933, the year the Nazis seized power in Germany.

At the age of two his mother immigrated to Israel, to Bat Yam, where sand dunes kissed the sea, remarried, and until the age of 21, after service in the naval commando, he did not know that his father was a well-known theater man who operated in East Germany.

In Israel, which burns from hot springs and a few rain showers, Tumarkin grew and became one of its original sculptures, and some believe it was the most important sculpture.

Always trying to be rebellious and defiant, holding on to non-conformism as if it were the fountain of life for him.

Others saw him as a kind of naughty and immature boy, whose rebuke shattered with empty force.

In short, artistic vulgarity.

Dozens, if not more, of his sculptures and monuments he has created over decades are in the public space. These inevitably created encounters between each other almost on a regular basis. In my youth, when I was growing up in Holon, his sculpture garden opened in front of the city hall, and so more than once, after visiting the municipal library, I was thrilled to wander through the sculpture garden he created. There, between whitewashed concrete walls like the trenches of a military post, I moved into the various spaces that serve as the backdrop for his sculptures, which house more than 20 iron sculptures made by him.

Today, during the corona breaks, when I arrive at Tel Aviv University on my way from the parking lot behind the main library to the office, I casually glance at his huge sculpture, "Occurrence," which stands in front of the Faculty of Art. And of course, every time I came to Rabin Square decades ago, when it was still called Kings of Israel Square, with the family for Independence Day celebrations to see fireworks shattering in the sky in a variety of colors - it was impossible not to stop in front of the "Holocaust" sculpture. Huge triangles, pyramids combined together to form a Star of David.

Tumarkin has created concrete and metal sculptures and scattered them around the country for decades. There was always something unique in his work with a powerful, fearless brilliance, touching on vulgarity and violence, presenting itself. Tumarkin did not stop at the skin that surrounds the person. He removed it and showed us the "inside" of each of us. No doubt he deterred many, often rightly so. He touched on his work in political protest, the illusion of the power and might of violence and left us much evidence of the weakness of the weapon. He revealed to us the terror of the war that surrounds the citizens and soldiers of the country. In any case he wanted to be a reflection of our face as a society, on the internal contradictions that exist in him and his son. Many of our artists have embraced international currents that prevailed in their time and brought them to the country. He sought sacrifice and resurrection, even if out of contact with art in the world. He wanted to create Israeli anxiety.

When Tumarkin came to his father in Germany and lived in his apartment in Berlin, he heard him say, "You are the Jews ...", referring to their unbearable stubbornness.

Tumarkin did not give up and replied, "I, the Germans, would stand one by one in front of the wall and shoot you," thus ending their relationship.

He did not round corners and sought to see things as they were, in their injury.

He searched in welded metal cuttings together for true originality, tailor-made violence that flooded with complexity and depth and sensitivity, even if faced with quarrel, anger, confiscation and exclusion.

More than once, unfortunate Jewish faces looked at us from his drawings, looking out of the Nazi death trains, and he called it Goethe, directing Faust and Mephisto in Buchenwald, and above the director carried the motto written on the gate of the concentration camp, "Each for himself."

In his vivid and expressive sculptures, Tumarkin sought to be Bertold Brecht's Middle Eastern stalactite.

He did not seek to hide, and dealt with the sense of exile and persecution, leaving a trail of mobilized art that required a redesign of being.