"Darkness Sees", a book by William Styron that was originally published in 1990 and translated into Hebrew a few years later, in 1996, is considered a breakthrough in the discourse on depression: the fact that a writer is as famous and successful as Styron, who wrote the novel Sophie's Choice - who is also working on a feature film starring Meryl Streep - confesses to a major mental crisis, was perceived as a sensation, and has become a pioneer in promoting openness in the debate on depression.

But today, when not only writers and poets but also the most ornate athletes confess that they suffer from depression and suicidal thoughts - if we mention just a few of the names: footballers Gianluigi Buffon and Andres Iniesta, swimmers Michael Phelps and Amanda Byrd, tennis player Serena Williams, Hahn players B.B. Jerry West and Delonta West and many others - the confession itself is much less breaking conventions than before.

The re-publication of "Visible Darkness" these days, with the publication of attic books and a new translation by Yehuda Meltzer - who corrected his own translation from 1996 and added a second ending to the one he wrote in the past - makes it possible to re-read it on its own.

It is now called as close and rich testimony to images of the disease that remains largely a "great mystery," as Styron wrote 30 years ago.

Refute an angry opinion.

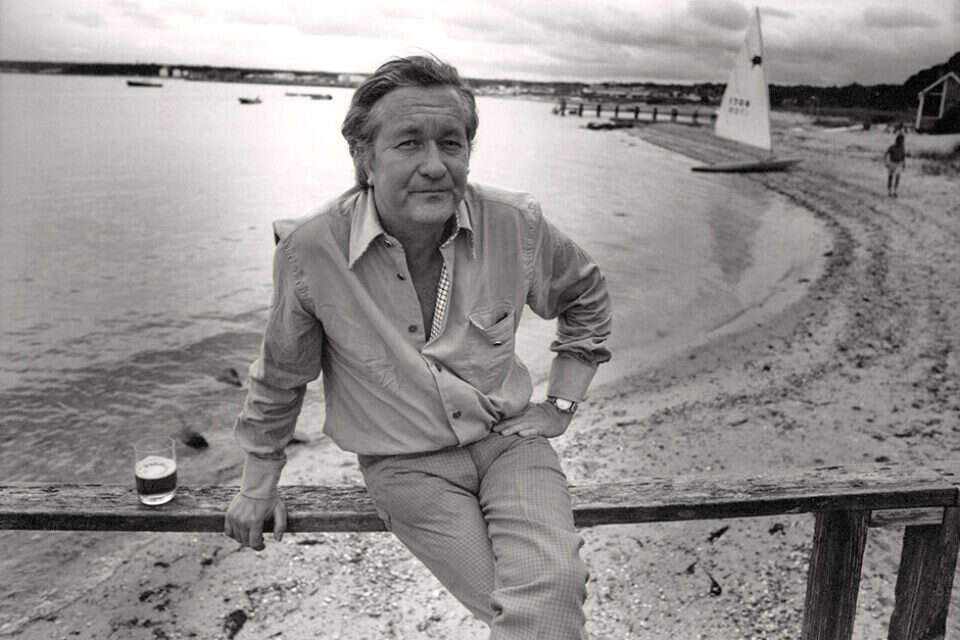

Dr. Yehuda Meltzer // Photo: Yehoshua Yosef,

"To me, Styron's achievement is in describing the painful existence of depression as more than a collection of psychiatric symptoms we know from the psychiatric instructor, the DSM," says Prof. Yossi Levy-Belz, a clinical psychologist and head of the Center for Suicide and Pain Research at the Ruppin Academic Center. "Styron not only describes despair, hopelessness, low self-esteem, difficulty making decisions and so on, but he first of all describes unbearable mental pain."

Levy-Belz testifies that he "teaches the quotes from the book in class - the feeling of the person suffering from depression that 'something has changed in me forever', the loss of control over emotions and the emotional dizziness that has sadness but also anger, guilt, hatred and disgust. Prof. Israel The late Orbach, who was one of the great theorists of suicide, created a sentence-based questionnaire from Styron's book, and when I passed the questionnaire to those who miraculously survived suicide attempts, they were surprised to find that someone had phrased things, that they were not alone in the experience of depression. "Styron was able to touch a deep sadness that the dry definition of depression does not cover, and was able to give it words that many people need."

"Depression is democratic"

"Visible Darkness" begins one evening in late October 1985. That evening, Styron writes, he came to the realization that his battle with depression could end in his death. He arrived in Paris to receive a respectable literary prize that included a check for $ 25,000, but at that time his depression had worsened to such an extent that for large parts of the day he was unable to function, and could barely get out of his room and attend ceremonies.

The award people found it hard to believe when Styron informed them that he would not be attending a meal they had organized in his honor, and after receiving the check and stuffing it into his pocket, it dropped from it to the floor and got lost.

Styron remarks that the loss of the check (which was eventually found) was not only a result of the confusion and inner distress he was in, but also an unconscious expression of the thought that he was in fact unworthy of the prize - an integral part of that self-loathing typical of depression.

But Styron does not content himself with describing depression as the negation of vitality (as the Hebrew term implies, which implies the suppression of oneness, the abolition of instinct).

It goes against the dryness of the English term, depression, which is also used in economics and geology to describe an economic downturn or land recession.

For, in his eyes what is attacking him is closer to a terrible and savage storm, which would have suited her a term like brainstorm, if he had not been already occupied by another meaning.

Serena Williams // Photo: GettyImages,

Styron writes about depression as a writer - not only because his writing paints the black tones of depression in images and distinctions that give this experience emotional and literary richness, but also because he emphasizes throughout the book the special connection between depression and writers, or depression and artists in general. Artists, he writes, and especially poets, are particularly vulnerable to this disorder - and he lists a long line of literary figures and artists who have suffered from depression and suicide - Van Gogh, through Virginia Woolf, Roman Gary, Mark Rothko, Ernest Hemingway, Paul Celan, Jack London , Anne Sexton, Diane Arbus, and up to Vladimir Mayakovsky, who a few years after criticizing the suicide of his contemporaries, the great poet Sergei Yesenin, committed suicide himself.

According to Dr. Yehuda Meltzer, there are those who have criticized Styron for his focus on artists. “This list of artists is very limited for several reasons: First, it focuses on Western writers and does not mention Japanese or Russian writers. But more than that, Steyron is angry that he is going through the depression on favorable terms, that he has fame, money, friends and a loving family, that he can afford to be hospitalized in an expensive hospital. That's why it was important for me to mention at the end of the day two other types of people who suffer from depression: on the one hand athletes, who are no less celebrities than him and no less rich than him, and on the other hand unemployed. "

Meltzer, however, criticizes "There is enough evidence to disprove this angry opinion: in the depths of the abyss and at the end of the rope, depression is probably still democratic," he writes.

"It does not help to say 'get out of this'."

Much of Styron's book is devoted to the long and confusing process of understanding the severity of his condition and the search for appropriate treatment.

At first, he attributes his mental crisis to alcohol withdrawal, because shortly before its onset he stopped drinking, after many years in which alcohol protected him, he said, from the demons of the mind.

And as soon as that defense faded, he found himself vulnerable and exposed.

But as it turns out, his depression had many other causes.

His father was depressed, so his depression has a significant hereditary factor, and on top of that, his mother died when he was a teenager, and her loss probably played a critical role in the development of the disease.

According to popular opinion among psychiatrists, such an early loss can create "almost irreparable emotional chaos", especially when the boy fails to complete the grieving process and carries with him a burden of guilt and anger that translates later in life into self-destruction.

On top of all that, there was also a drug issue. To treat his insomnia, Styron used, on his doctor's instructions, a sedative called "Halzion", which later became clear to him that one of its side effects was depression and suicidal thoughts (the use of the drug is no longer common in Israel).

Styron is very critical of his psychiatrist: he criticizes him for his "light hand" in dispensing psychiatric pills and the stigma he had about being hospitalized in a psychiatric hospital, which is why he tried to persuade him not to be hospitalized - while in the end it was hospitalization that cured him.

But Styron did not seek to turn his personal experience into a flagship case against the uncontrolled use of sedatives and painkillers - which is indeed reaching epidemic proportions in the United States today - or to mobilize in favor of a critical campaign against the psychiatric establishment. And its treatment, so that unfounded conclusions can be drawn from the experiences of an individual, "he writes.

"His psychiatrist was really terrible," adds Meltzer, "but there are enough people whose experience with psychiatrists and drugs is different. So the message from the book is not anti-psychiatric, but do not wait too long before going for help, and if necessary - also "To be hospitalized. The message, if there is one, is not to be afraid of the stigma."

Levy-Belz also agrees that "the public stigma regarding depression and suicide has not changed enough. Even today, with all the changes the discourse on depression has undergone since the book was published 30 years ago - thanks in part to social networks and our growing tendency to externalize, especially Experiencing anxiety and we all talk about anxiety - the vast majority of people who suffer from depression, about 80 percent of them, do not seek treatment.

"The ability to reach people who need treatment has not yet been exhausted. The depressed person himself does not recognize well enough what he has, and in any case his belief in being able to help himself and in the possibility that others will help him is damaged, because of his condition. "Tell him, 'Get out of this,' 'Be strong.'

Gary novel // Photo: GettyImages,

"Warriors do not come"

In the end of the new thing that a waiter writes, he raises the possibility that Styron also suffered from battle shock, which could have been another factor in the background of his depression.

Styron does not write about himself as a battle shock victim, but he served in the Marines as early as World War II, when he was stationed in Okinawa, and was also drafted in the Korean War in the 1950s.

He wrote about his military service in his stories, one of which, "The Long Journey," is, he says, autobiographical: at the end of the novel Styron writes that the events described in it not only occurred, but recurred in his mind while writing in a nightmare reality that could not be questioned. About that period of his service in the Marines he said in one of his interviews: "The myth at that age is that you are going to live forever. I never believed it, and my friends did not believe it. I thought I was going to die."

Prof. Rivka Tuval-Moshiach, a clinical psychologist from the NATAL organization, which provides psychological assistance to victims of terrorism and war, and from Bar-Ilan University, explains the closeness between battle shock and depression. "The feeling that life has no meaning, suicide - but when the post-trauma is left untreated it causes such a great disruption to life that depression is its obvious side effect.

" What often happens in post-trauma following war, "says Tuval-Moshiach, Warriors do not come for treatment, or do not continue treatment for a long time, and while for some things will indeed pass by themselves, for others things may resurface after many years. Sometimes they will feel depressed, have difficulty in a relationship, have difficulty concentrating, have difficulty committing; Sometimes we find them wandering between classes at the university. Many times it takes a long time before they reflect and give things a go. Terribly depressing to say,I am a victim of the war. "

Vladimir Mayakovsky,

Letter to readers

Meltzer acknowledges that the translation did not justify the reissue of the book.

"I can not argue against the previous translator, because he was me," he says with a smile.

Although, naturally, during the two decades since the previous translation, Hebrew has undergone changes, it is not because of this that the publication of "Attic Books" chose to republish the book.

The main reason why a waiter decided to republish the book is, he says, related to the optimism with which the book ends.

At the end of the book, Styron is released from the hospital where he was hospitalized, believing that here he is - he manages to overcome his mental crisis and become a better person.

"In general, the whole matter of recovery is described in the book very quickly and briefly in relation to the long decline," says Meltzer, "and readers feel that there is some cloud left. After more than 20 years, I thought we should tell what happened to Steyron in the end, Of Styron before his death. "

As Meltzer writes at the end of the new thing, more than a decade after the book was published, depression returned, and this time with greater intensity. Styron faded for six years, until he died in 2006, "pneumonia," according to the official announcement, but left behind a letter in which he wrote: "I hope readers of 'Visible Darkness' - past, present and future - will not be disappointed by the way I died. "The battle I have waged against this vicious disease since 1985 has been successful, and it has brought me 15 years of a comfortable life, but in the end, in the war the disease has won."

And yet, Styron adds: "Everyone must continue the struggle, because there is always a chance that you will win the battle and there is almost certainty that you will win the war." If not in the case of Styron, perhaps in the cases of his readers.