Enlarge image

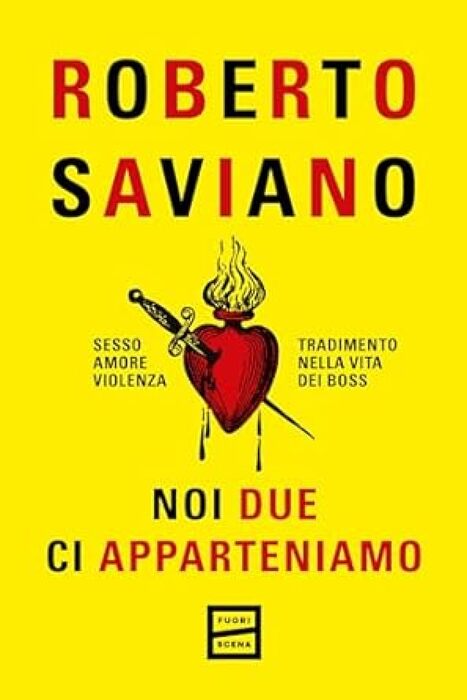

A villa belonging to Cosa Nostra hitman Giuseppe Greco.

Photo: Alessio Mamo

The old town of Palermo, mountains and the sea: That's the view from the villas clinging to the side of Monte Gallo on the Sicilian coast. But there is nobody in the homes to enjoy the vista - just birds and rats. A company linked to mafia boss Michele Greco initiated construction on the colony in the late 1970s, and by the time public officials put a stop to the project, 170 mansions were already under construction. Today, the collection of mafia-villa skeletons is known as "Pizzo Sella," or "Hill of Shame."

In countries like Italy and Mexico, where crime syndicates have significant influence, mobsters and cartel bosses frequently play a significant role in the cityscapes of their hometowns. They are involved in sizeable construction projects as a way of profiting off of tendered contracts or to launder money, and they build luxurious mansions as status symbols for themselves and their families. Some even have complex underground bunkers and tunnels built to help with smuggling or to serve as emergency escapes - or they live below ground entirely.

"Unfortunately, in most southern Italian cities, there are remnants of mafia structures that have changed the character of these places," says Sicilian photographer Alessio Mamo. He has documented the villas and ruins of the Mafiosi with his camera - creating a photographic record of how aggressively the clans have changed the appearance of public spaces in the region.

"Architecture and the drug trade are inextricably linked," agrees the Mexican architect and city planner Eloy Méndez, who researches "narco-architecture" at the University of Puebla.

Real-estate investments from organized crime, he says, have created entirely new cityscapes in Latin America.

Their pompous structures are like "their own language, with which they want to show off and set themselves apart."

Often, he adds, they are kitschy and excessive.

The Jardines del Humaya cemetery in Culiacan, the cradle of the Sinaloa cartel, is a prime example.

Narco bosses and their families compete to build the most ostentatious mausoleums there - structures which are reminiscent of temples and colonial-style palaces.

They include elements like onion domes, cornices, vaulted roofs, arches and columns.

The structures are also symbols of power, their presence helping mafia clans and cartels dominate the public space and control the surrounding areas.

But governments and civil society are trying to take back the cities.

Since 1982, Italy has confiscated more than 36,000 mafia-owned properties.

"Confiscation is one of the most effective instruments in the fight against organized crime," says Zora Hauser, who researches the mafia at the University of Oxford. Depriving them of assets, she says, disrupts their operations and acts as a deterrent.

"Most effecting, though, is when assets, companies, property and buildings are returned to society," Hauser believes.

"It is a sign that the state and the people have retaken control."

It is, in fact, what mobsters fear most, she says: Losing control over their territory.

According to the anti-mafia organization Libera, around 1,000 Italian municipalities have received confiscated buildings or properties from the state for conversion to public use.

In addition, some 900 non-profit organizations or collectives administer former mafia holdings.

The GOEL Cooperative Group in Calabria also benefits from the Italian strategy of redistributing former mafia-held properties.

The group currently uses three former mob buildings, but they have also learned that the mob doesn't give up its property without a fight.

In Calabria, from which the brutal 'Ndrangheta runs its global empire, farmers, business owners and others have joined together to form the cooperative to stand up to the mafia and push back against their threats and demands for protection money.

GOEL also operates several social initiatives in areas like organic farming, tourism, sustainable fashion and organic cosmetics.

GOEL has thus been able to provide jobs to around 400 people in one of the poorest and most corrupt regions in Europe, a place where the mafia is the largest employer and where the state has largely lost control.

One formerly mafia-owned building houses GOEL workers, while seamstresses work in another, producing clothes for the organic fashion label.

The most recent addition is a former villa that used to belong to a mafia boss.

The initiative has transformed it into a hotel.

The city even paid for new furniture and guaranteed that no rent would have to be paid for 10 years.

Water and electricity are also provided at no cost.

But 10 days after GOEL won the tender for the structure, mafia members forced their way in, damaging and stealing parts of the water-supply system and causing 50,000 euros in damage.

The anti-mafia initiative is familiar with such attacks.

On one occasion, mobsters burned down a farm, destroyed tractors and demolished warehouse inventory.

Since then, the team has been throwing a party each time the mafia strikes.

"When people fall into a depression and give up hope, they are easier to control," says Vincenzo Linarello, head of the GOEL Cooperative Group.

"When the 'Ndgrangheta attacks us, we respond with festivals that give people courage."

They throw parties, collect donations and stage publicity campaigns to shine a spotlight on the methods used by the mafia.

Linarello says that the threats have grown more infrequent.

"They have apparently understood that they make us stronger with every attack."

Other regions have sought to emulate the Italian model - like Berlin.

In the German capital, plans are afoot to also make confiscated properties available to non-profit initiatives.

In 2018, officials confiscated 77 properties belonging to the Remmo clan, including apartment buildings and flats, but also a villa and an allotment garden.

Plans call for the villa, located in the Neukölln neighborhood of Berlin, to be transformed into a youth center.

First, though, administrators must force out the current tenants, all of whom are family members of the clan.

Mexico, for its part, will soon be raffling off properties confiscated from corrupt politicians and drug lords.

In mid-September, a special lottery will be held as part of which a house in Culiacán will be given away from which Joaquín "El Chapo" Guzmán fled in 2014 - as will a villa near Mexico City which used to belong to Amado Carrillo, the former boss of the Juarez cartel.

For 250 pesos per ticket, the equivalent of around 11 euros, participants will have the opportunity to win a narco-house.

The government plans to use the revenues from the raffle to boost its coronavirus vaccination campaign.

Not everyone is a fan of the Mexican plan.

Crime expert Edgardo Buscaglia believes the raffle is just a "show."

He says the lottery will merely "return a couple of assets to the people."

Mexico, though, Buscaglia says, is lacking a nationwide strategy and laws requiring judges to redistribute all confiscated assets to civil society organizations that are led by victims of organized crime and which help out those who have been harmed.

The return of such properties "isn't a gift," he says.

They should be used to help victims reintegrate into the working world and society.

This piece is part of the Global Societies series.

The project runs for three years and is funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Expand section What is the Global Societies series?

The Global Societies series involves journalists reporting in Asia, Africa, Latin America and Europe on injustices, societal challenges and sustainable development in a globalized world.

A selection of the features, analyzes, photo essays, videos and podcasts, which originally appear in DER SPIEGEL's Foreign Desk section, will also appear in the Global Societies section of DER SPIEGEL International.

The project is initially scheduled to run for three years and receives financial support from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Expand How much funding are we getting? Area

The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF) is funding the project for a period of three years at a total cost of around € 2.3 million.

Open area Does the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation have editorial influence?

No.

The foundation exerts no influence whatsoever on the stories and other elements that appear in the series.

Expand area Do other media outlets have similar projects?

Yes.

Large European media outlets like the

Guardian

and

El País

have similar sections on their websites - called "Global Development" and "Planeta Futuro," respectively - that are likewise funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Has DER SPIEGEL produced similar projects in the past?

In recent years, DER SPIEGEL has complete two projects with the support of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the European Journalism Center (EJC): "Expedition Beyond Tomorrow," about global sustainability goals, and the journalist refugee project "The New Arrivals," which resulted in several award-winning features.

Where can I find all stories and elements published as part of the Global Societies project?

All Global Societies pieces will be published in the Globale Gesellschaft section of the DER SPIEGEL website;

a selection of articles will be made available in English on the International website Global Societies.