Jessica DuLong, now chief engineer emerita, appears in 2008 in the engine room of the 1931 fireboat John J. Harvey.

(CNN) -

Isaac Rothbart's twins have always known their father doesn't like fireworks.

But he had never told his children why.

Then, while celebrating their fifth birthday at Disney World, the family ended up near an unexpected fireworks display.

Rothbart "did not react well."

His wife realized that he was upset and brought the whole family home.

It was then that Rothbart and his wife decided it was time to have the conversation with the kids.

Rothbart had made an HBO documentary specifically geared toward teaching children about the September 11 attacks.

That would be the beginning of the conversation.

20 years after the 9/11 terrorist attacks: fast facts you need to know

A pandemic with many deaths, insurrections, terrorist attacks and countless videos on police brutality and hate crimes, put us parents under the continuous pressure of how and when to share worrying and traumatizing news with our children.

Those pressures are further compounded when we or our loved ones are personally affected.

Just by chance, Rothbart and I ended up arguing about how to tell children about the deadliest terrorist attack on American soil.

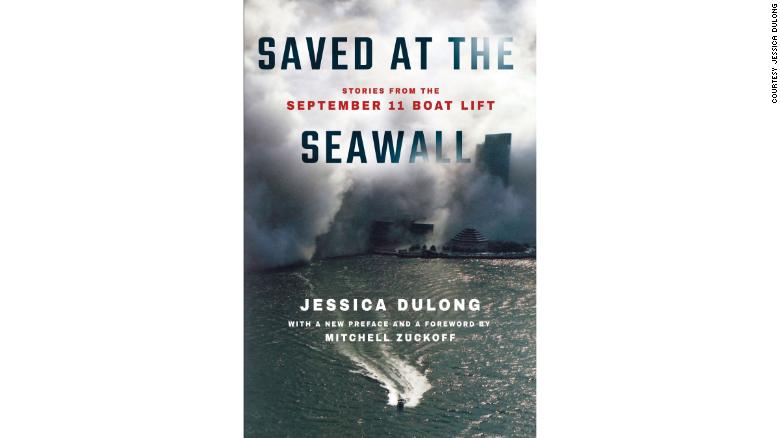

At the time, Rothbart, chief financial officer for the New York Police Foundation, was trying to help me locate a photo of that terrible day in fall 2001. The cover of my book, "Saved at the Seawall: Stories from the September 11 Boat Lift, "was about to hit the press.

advertising

Jessica DuLong's book went on sale on May 15.

"Could it be one of these?" He asked before sending another file.

We talked on the phone while emailing each other and he rummaged through old hard drives for digitized negatives.

Throughout all my years of working on this book, I had carefully studied hundreds of photographs from that day.

Yet somehow clicking on this particular image stopped me in my tracks.

My "ooph" came out involuntarily.

The photo was not the most moving or revealing I had seen.

Taken from a New York Police Aviation Unit helicopter, the image on the contact sheet was tiny, rather dark, tilted at an odd angle.

But something in the enormity of the dust cloud photographed from such a height and distance brought out all the horror.

"Sorry," I replied, to explain my prolonged silence.

"After all this time, I thought I was immune."

"Okay," Rothbart said.

"That day I was at Stuyvesant High School."

That quick revelation communicated entire worlds of understanding.

"I guess that's why I keep hiding this story from my kids," he said.

The challenge of telling your children

It has been almost 20 years since I served at Ground Zero as a retired shipboard engineer on the New York Fire Boat John J. Harvey.

But I have not yet told my 9 and 5 year old children about the terrorist attacks, nor that I was there.

The countless hours that I have spent reporting and writing this book have taken place behind closed doors, where I rush to bury the evidence in my desk rather than face questions from my children.

However, my conversations with Rothbart convinced me that this is the year to share the truth.

I have read all the Child Mind Institute tip sheets: "How to help children deal with scary news", "How to help children cope with grief", "How to talk to children about racism and violence ".

The latter's subtitle promised exactly the help she needed: "Supporting Children While Navigating Your Own Great Emotions."

But the third point in "Scary News" - "modeling calm" - left me much less optimistic.

I contacted David Anderson, vice president of school and community programs for Child Mind, who helps parents and caregivers discuss all kinds of difficult topics.

I later discovered that Rothbart had intuitively used many of the approaches Anderson recommended with his own children.

Anderson's main message for parents facing difficult disclosure decisions is quite simple: "Your children are prepared to hear what is going on in the world - from you."

That's much better, he argues, than being heard from others, especially someone who is not "a close attachment figure" with whom children can more easily process their feelings.

"The real question is," he says, "are you prepared to tell them?"

In a word, no.

But I'm trying to get to that.

I acknowledge that my silence is not serving my need to protect my children.

Rothbart's story inspired me to search for that HBO documentary.

It turns out that filmmaker Amy Schatz created "What Happened on 9/11" after hearing a curious third grader googled "9/11 attacks" with a friend on a play date.

Ouch.

My oldest son is in third grade.

At what point can my efforts to protect him and his younger brother become a threat?

My 5 year old son has mastered Google voice commands.

My favorite search, "invisible goat images", could easily turn into something more sinister.

"We want children to have us there to help them process their emotional reactions," Anderson insists, "and only be exposed to content that they are developmentally ready for."

That last warning made me stumble a bit.

How can parents who are not child psychologists know what children can handle and understand?

"Give him a few basic facts and then see how he reacts," advises Anderson.

"What we really try to emphasize to parents is that this process of providing their child with data, gauging their emotional reactions, validating those emotions, and trying to answer their questions is repeated thousands of times throughout their development."

Okay, but what about the "calm model" sticking point?

One of the Child Mind's tips warned: "If you talk to your child about a traumatic experience in a very emotional way, he will likely absorb your emotion."

The post-traumatic stress disorder that I continue to suffer from two decades after 9/11 means that "calm" is not my default choice when it comes to this topic.

The resource of literature

By fotuna, Maira Kalman has provided an ingenious and effective tool for teaching children about September 11: her picture book "Fireboat: The Heroic Adventures of John J. Harvey."

I appear as the character of Jessica, who is "at the controls in the noisy engine room."

The signed copy Kalman gave me still smells of ship oil and the pages are wrinkled from some mishap from exposure to water.

I have never read this book to my children.

I could not bear the page that represents a sky "full of fire and smoke".

Maira Kalman's illustrated book "Fireboat: The Heroic Adventures of John J. Harvey" by Maira Kalman features author Jessica DuLong.

"Their goal is to prevent frightening fantasies from being fostered," the councils said. How was he going to do it, considering the horrible truths of that day - that the terrorists intentionally used planes full of passengers as missiles - that people jumped from skyscraper windows to escape the scorching heat of the fires caused by the jet fuel, and that thousands of people perished when the towers collapsed?

I was comforted by Rothbart's experiences as he told his children.

When he was a senior in high school, he'd watched horrors unleash from south-facing windows in a ninth-floor classroom.

"We saw how people came to the windows and waved flags to try to get help," he recalled.

"It was apparent very quickly that they weren't going to come out."

DuLong appears in the engine room of the fire engine, where he worked.

Along with his classmates, that day at school he learned to distinguish falling debris from people by the way their limbs flailed as they fell.

"My kids don't know," Rothbart explained, lengthening the last word for emphasis.

He was quick to clarify that there are details that he has not shared.

He used Schatz's film to broach the subject, inviting his twins, who are about 6 years old, to see it with him.

One of the sons refused, and his parents respected that decision.

"It's still on the DVR. So when you're ready, you'll see it."

But the other sat with his mother and father, who did their best to answer his questions simply and directly.

"He asked us to maybe see him again. We said, 'Sure, but it could be without dad.'

Instinctively, Rothbart had followed the Child Mind Institute's recommendation to seek support if a parent is dealing with their own trauma.

It's important, Anderson explained, to find a balance between modeling calm and letting children see your true emotions.

"Difficult news events - terrorist attacks, acts of racism - are incredibly emotionally disorganizing for anyone. We want children to know that it is appropriate to feel sad or upset or deeply affected by traumatic events. At the same time, staying regulated is essential to help the child process their emotional reactions, "Anderson said.

Trauma can trigger "re-experiencing," he explained.

If that's a possibility, it's wise to ask for help from "another trusted adult who can take over if you're getting too much."

Anderson also said it is "emotionally healthy" to build a "way out" before a difficult conversation.

"It's perfectly fine to say to a child, 'Listen, it's very emotional for me to talk about this. It's important that you listen to it, but I also have to make sure that I stay in a place where I can have this conversation,'" he explained. .

It's also crucial, Anderson said, to properly frame the information.

Speaking of terrorist attacks or mass shootings, he recommended: "Explain to your child how unusual this type of event is. Although it is much more frequent than in the past - in fact, disturbingly frequent - it is still relatively unlikely that the child will have that experience. "

The same, he explained, cannot be said for racial violence or sexual assault, of course.

The importance of talking about our children's emotions

Overall, both Anderson and Rothbart assured me that sharing 9/11 with my children will not require flawless execution.

"Life is not about reacting perfectly to everything that happens," Anderson said.

It is about finding "ways to face and be prepared for any obstacle that life throws at you."

After all, that is the most important lesson.

If we protect children from any emotional events that may occur, Anderson warned, we will prepare them for "a huge awakening when they reach adulthood."

Instead, our job as parents is to help our children practice talking about emotional topics.

"Parents (and caregivers) are the best absolute mediators for building children's emotion regulation circuits," he explained.

This will be the year.

I will prepare the scaffolding for a quiet conversation.

I will read Kalman's book "Fireboat" to my children and show them the photo of Mama working in the engine room (in a classic writer's maneuver, it will help me hide behind a character on the page).

Finally, I will show my children my own book that documents the momentous history of rescue actions that have sorely gone unnoticed.

I will tell you about the lifting of the ship and the efforts of so many lifeguards and volunteers that day: that people help each other in disasters, displaying the kindness, resourcefulness and humanity that calls them to action.

I will teach you that hope and wonder illuminate even the darkest moments.

Jessica DuLong is a Brooklyn-based journalist, book contributor, writing coach, and author of "Saved at the Seawall: Stories from the September 11 Boat Lift" and "My River Chronicles: Rediscovering the Work that Built America."

11-S