The Netherlands (CNN) -

In the characteristic Dutch drizzle, Anneke van Lelieveld bundles up in her bright orange sweater at her home by the New Merwede River, turning to look at the wetlands behind her garden.

He loves the view.

He loves being able to dock a boat just a few steps from his garden.

He loves to see eagles and beavers.

But within her joy there is a hint of reluctance.

Anneke van Lelieveld used to look out over her neighbor's farmland.

Now their fields have disappeared, and in their place are wetlands.

To fight the climate crisis, he says, such a change is "necessary even when it breaks your heart." "My mixed feelings is that this was my neighbor's land," says van Lelieveld.

"I am sad because I know how sad my neighbor is. Because he is giving up his land."

What used to be his neighbor's farm, walled against the nearby river that posed a constant threat, is now carpeted with water.

It is flooded, on purpose, to absorb the water when the river rises.

It is not suitable for agriculture, but Van Lelieveld can live here.

A small and simple dam keeps your house and some others on the street dry, even if your patios are not.

All of this is part of an ambitious climate project aptly named “Room for the Rivers”.

advertising

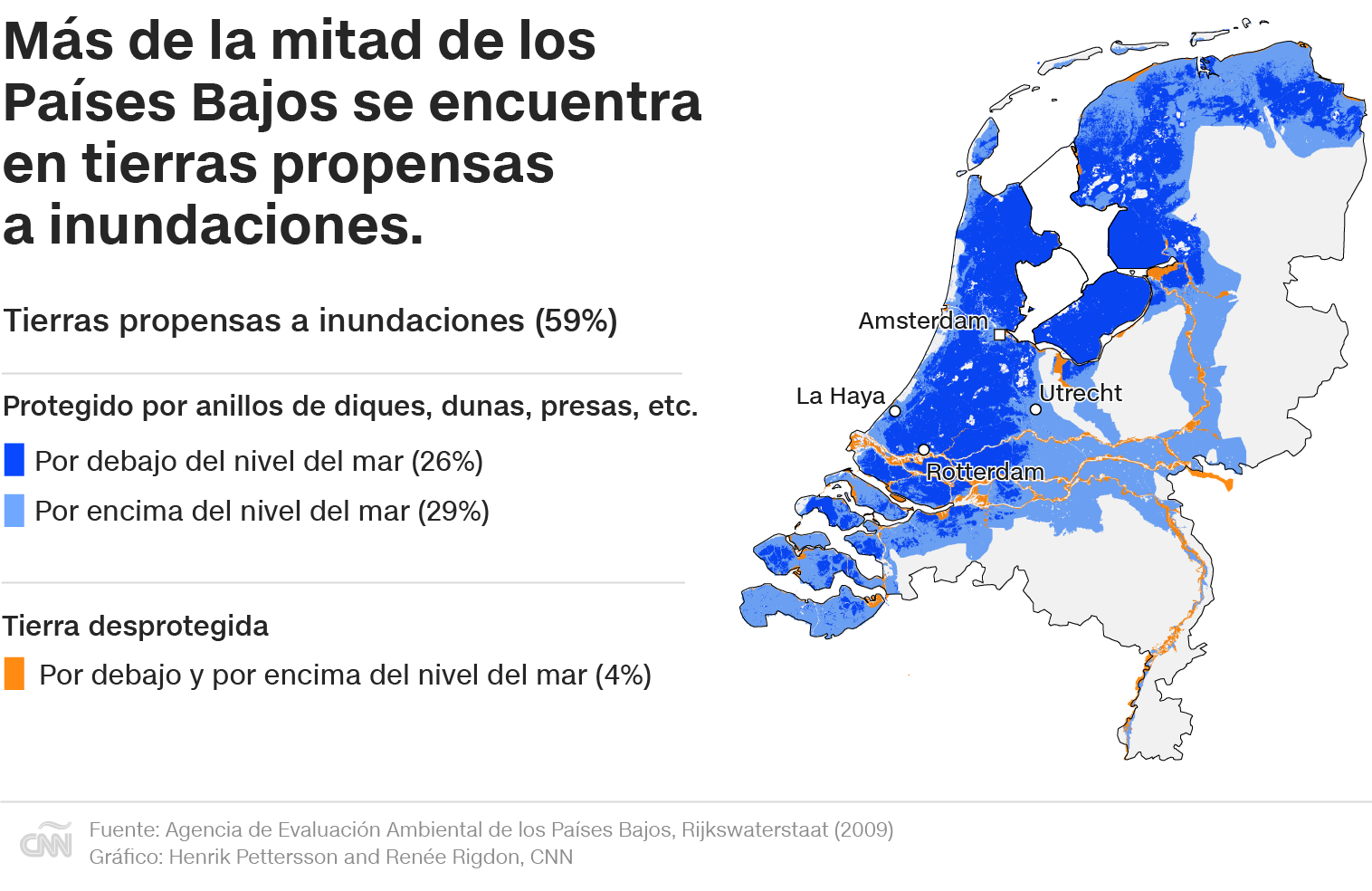

The Dutch have struggled for centuries to keep water off the ground in their low-lying country, more than a quarter of which is below sea level.

Although "adaptation" seems like a boring word in climate parlance, the Dutch have long adapted to the vagaries of the water.

Pumps, dikes and gigantic mobile dikes protect the country, at least half of which is threatened by floods.

Nothing in the example of the Netherlands is perfectly reproducible: its landscape, its tradition of sharing political power and its culture of water awareness are unique.

But there is a lot we can learn.

The climate crisis only intensifies that vulnerability.

Erratic weather is no longer a problem for the future - it is clearly here, in most parts of the world - nor is it a problem of extremes only, like wildfires and flash floods.

It's also a matter of organizing, as governments and individuals now make life-and-death decisions in the face of potentially worse threats to come in an even warmer world.

WHO says the climate crisis "is the greatest threat to human health" and urges world leaders to take action

The experience of the Netherlands has been very useful for people who have had water problems around the world.

In the 17th century, King Charles I asked a Dutchman, Cornelius Vermuyden, to help him drain the Cambridgeshire marshes in England.

When New York City was devastated by Hurricane Sandy in 2012, the United States government turned to the Dutch for help.

When the Ever Given ship ran aground in the Suez Canal, a Dutch company was hired to remove it.

The New Merwede River is a major thoroughfare for commercial ship traffic from the port of Rotterdam.

But climate change means that these brute force methods that have worked for centuries will not always be enough.

A dam will eventually give way under its own weight, and they cannot be increased at will as this only increases the risk when it fails.

In the 1990s, the government of the Netherlands began to change course, better understanding that the natural state of water bodies exists for good reasons.

An example is that of uninhabited lowlands along rivers that could flood and help absorb water when it rains heavily upstream.

The "Sleeping Beauty" forest is dying.

Not the only climate crisis facing Germany's next chancellor

That meant doing something unusual for the Dutch: tearing down some of the walls that previously held back water, and displacing people off the land.

https://cnnespanol.cnn.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/1-Netherlands-Noordwaard-loop-1-a.mp4

"This is the result" of climate change

To understand why the project is so vital, at the moment, the headwaters of the rivers that flow into the Netherlands give us an idea.

About 300 kilometers from the Rhine, from the humble home of Van Lelieveld, is the Ahr, a tributary that winds through the picturesque hills of the West German wine region.

It was here in July that the waters rose more than ever in the collective memory of Dernau, a small town nestled between steep slopes of vineyards.

"It's not easy to find the words for it," says Lea Kreuzberg, 23, who on July 14 was sitting in her apartment above the winery she runs with her father.

https://cnnespanol.cnn.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/9-Ahr-Valley-1-a.mp4

Dernau, in the German Ahr Valley, was devastated by the June floods.

Credit: Martin Bourke / CNN

In a few hours, the waters overflowed in the patio, submerged the ground floor and went up to his apartment.

Kreuzberg, her boyfriend, and two warehouse employees took refuge on the top floor of the building.

They spent a terrifying night together, conserving the phone's battery to communicate with Kreuzberg's father, who was on vacation in Austria.

The water finally peaked, and then it slowly receded.

Finally, at 5 p.m. the next day, they were rescued.

"In the early days, the rain made me very uncomfortable," Kreuzberg said, referring to the moment immediately after the floods.

"When it started to rain a little more, the emotions flared up again and I started crying," he added.

"When we come back here, it won't be easy to live here without being afraid."

The human impact of the July floods was devastating.

In the state of Rhineland-Palatinate alone, 133 people died.

In all, 180 died in Germany and 39 in Belgium.

One of the victims has not been found.

According to the European Organization for the Exploitation of Meteorological Satellites (EUMESTAT), between July 14 and 15 almost 15 centimeters of rain fell in a single 24-hour period, causing widespread damage not only in Germany and Belgium, but also in France, Luxembourg, Switzerland and the Dutch province of Limburg.

Lea Kreuzberg in the winery she runs with her father.

He had a terrible night upstairs when the waters flooded the ground floor.

The region is no stranger to flooding.

But EUMESTAT said the July rains were "particularly devastating" and that such intense storms "are increasingly likely with climate change."

For Franziska Schnitzler, standing among the ruins of her family hotel and restaurant, that connection is clear.

The 350-year-old wood-framed building it occupied was deemed unsafe and torn down.

In Germany's Rhineland-Palatinate region, nearly 15 centimeters of rain fell in a single 24-hour period between July 14 and 15.

Dernau, in the Ahr Valley, was devastated.

"We live with climate change," says Schnitzler.

"And this is the result".

And for the young and old alike, climate change is compounded by a mental health crisis.

In the days after the floods, three people from Dernau took their own lives.

"She was the grandmother of one of my best friends," says Schnitzler.

"One night he woke me up and said, 'My grandmother, my grandmother, my grandmother.'

"It was very hard, losing someone after the flood."

Franziska Schnitzler's family hotel and restaurant was so damaged by this summer's floods in the Ahr Valley, Germany, that the building had to be torn down.

A wake-up call for the Netherlands

People who have given up their houses and land in the Netherlands did not do so primarily for themselves, but for others.

They were asked to sacrifice themselves to protect the inhabitants of upstream and downstream cities, for whom floods pose a much more serious threat.

It was the major river floods in 1993 and 1995 that served as a "wake-up call," says Hans Brouwer, who for years has managed projects for the Netherlands government's Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management.

In 1995, a quarter of a million people from the Netherlands were evacuated to protect them from rising rivers.

"We focused for decades on the sea, and on defending ourselves from the swells," he recalls.

"And then our rivers surprised us. And in 1995 the decision was made to evacuate a quarter of a million people. That was shocking."

Those floods coincided with some of the early reports from the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change sounding climate alarms.

"We realized that we could expect even more water from the rivers, and at the same time it would be difficult to get rid of that water due to rising sea levels," Brouwer said.

Our future underwater: what sea level rise will look like in cities around the world

Nol Hooijmaijers stands next to the mound on which his dairy farm was rebuilt.

Starting in 2010, the authorities removed the dike that protected this strip of land from the Bergse Maas River, allowing farmland to flood as the river rises.

About 15 years ago, Brouwer's colleagues approached Nol Hooijmaijers, a dairy farmer, and told him that that eye-shaped patch of land that he and 17 other families called home would soon have to become a floodplain.

"We had already been through 93 and 95. So we thought at some point something would have to be done. We just didn't know what it would be," said Hooijmaijers, who is now 72 years old.

"Then when the government came in and said that this area could be used as a floodplain, yes, that was of course a huge shock."

"We were convinced that we could stay here and farm for generations."

He and his fellow farmers got together and decided they would "try to turn a threat into an opportunity."

While some left rather than face heartbreak, Hooijmaijers, his wife and seven other families decided to stay.

They convinced the government to build huge twenty-foot-high man-made mounds, or "terps," on which to relocate their farms and houses.

In turn, the northern dike that had protected their lands was lowered, allowing floodwaters to pour over them.

The change, "even when it breaks your heart"

The Room for the Rivers project was a monument to planning, foresight, and what can be achieved when government and citizens engage in collective action.

Thirty-four projects - with a total cost of US $ 2.66 billion - mean that the rivers of the Netherlands can now absorb 25% more water than in 1995.

During the huge rains in July, Van Lelieveld watched the river rise, speed up, and turn brown from sediment and debris.

Now Noorwaard can be flooded on purpose when the New Merwede fills with water.

The river can carry more water without raising its level.

"That's when you can see the role of the region, because here we didn't have any high water problem," he said.

"I hope people understand, what I have sacrificed to make this happen."

Brouwer described a "paradigm shift" in which engineers realized that "we don't even always understand how nature works, but we take it seriously."

The design of the area in which Van Lelieveld lives, he explained, was based on a map from a century ago, "not knowing exactly why it worked at the time, but trusting that nature made the right decisions."

The project created the wetlands that flooded its former neighbor's farm and are now home to vast flocks of birds.

When you go out in your boat, you think of the farmer's struggle to get decent compensation for his land.

"On the one hand, I don't dare to enjoy it, because I also experienced that sadness and saw what it did to people," he says.

"But on the other hand, I am very proud of what we have achieved in this region. And that we can also be an example, that it is possible."