Americans who are concerned about the future of their democracy can learn from the system they helped build in Germany.

After the defeat of Adolf Hitler, it was the United States that introduced democracy in a destroyed and divided Germany.

But today Americans, concerned about the current state and future of their democracy, can learn lessons from the German experience.

An example: Americans are only now starting to grapple with the legacy and history of racism, but unlike in Germany * this is just another politically polarizing topic.

This article is available for the first time in German - it was first published by

Foreign Policy

magazine on October 17, 2021

.

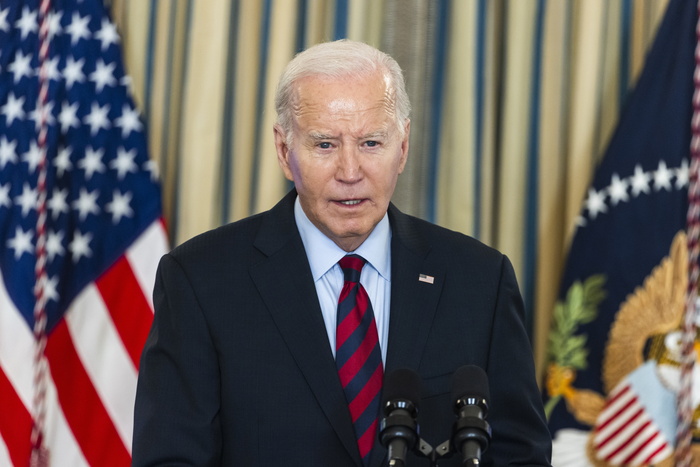

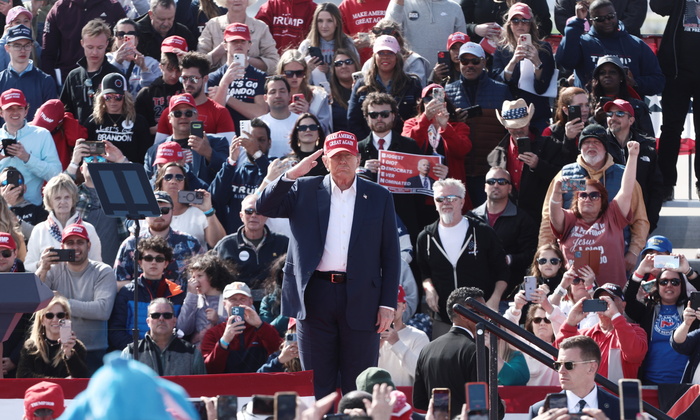

The German federal election was in stark contrast to the recent presidential and congressional elections in the United States. In one election, voters spoke out in favor of rationality, parties from the center, adult leadership and the rejection of an extreme nationalist alternative. In the other election, the re-election of a right-wing national authoritarian politician who had incited his supporters to attempt a violent overthrow * and who still has the support of over 30 percent of the electorate was barely prevented. The first choice was of course the one in Germany, the second in one of the oldest democracies in the world, that of the United States of America.

In the past year there was a notable role reversal. After all, it was the United States, after the defeat of Adolf Hitler, who introduced democracy in a destroyed and divided Germany. The United States provided its expertise, including that of German emigrants such as Carl Friedrich and others who helped draft the West German constitution. They laid the foundation for a successful democracy at a time when there were only a few democrats in Germany and when many had collaborated with the Nazi regime or actively supported it.

The prospects for success seemed bleak, but in contrast to the failed Weimar Republic, the new republic had time to consolidate - not least because of the market boom known as the economic miracle.

After the Cold War froze the division of Germany, the country had 40 years to prepare for national reunification - a long, difficult and still incomplete process of integrating 17 million East Germans who had not experienced democracy for almost 60 years .

What the German federal election taught America about democracy

Today, Germany is a role model around the world and is viewed more positively in many countries than the United States, as a recent international survey by the Pew Research Center shows.

What lessons can Americans, concerned about the current state and future of their democracy, learn from the German experience?

Limiting the Role of Private Money:

As Robert Kagan, Martin Wolf, and other commentators have pointed out, US democracy is in great trouble because of a number of structural changes.

The most important of these is the increase in social and economic inequality and the concentration of wealth in a small group of people who would be referred to as oligarchs in other countries.

The system's vulnerability to large campaign donors and black money has

grown exponentially

since the 2010 Supreme Court decision (

Citizens United)

that allowed corporations and other outside groups to spend unlimited amounts on elections. Although Germany has experienced many campaign funding scandals in the past, particularly the scandals at the end of Helmut Kohl's chancellorship, it has maintained a relatively open, transparent, and limited campaign funding system that primarily uses public funds. The country has been spared the scandals that ravaged the US system.

The Parliamentary System:

One of the great systemic weaknesses of the American system is what the historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr. called the "imperial presidency". Presidential systems are more prone to autocrats than parliamentary democracies. The personalization of power and government is something that the Germans learned to avoid after their experience with the Hitler regime. In addition, the German proportional representation system, in contrast to the American and British majority voting system, produces multi-party coalition governments that reward consensus and compromise.

There is not only a separation of powers between the legislature and the executive, but also between the coalition and opposition parties at federal and state level, which enables both functioning majorities and clear responsibilities.

And that rewards the way to the middle, because the big parties have to be able to cooperate with one another in order to form a government.

The opposition parties are also involved in policymaking, as the chairmen of the Bundestag committees are distributed among all parties in parliament and are not just controlled by the majority.

The Bundesrat, which represents the incumbent governments of the 16 German federal states, is another level for the necessary cross-party compromise.

The role of the political parties:

Thanks to public funding of election campaigns, the parties, not the candidates or private donors, control recruitment, and there is party discipline in parliament. All of this limits the possibilities of individual political actors to evade party control. It is about the party and not about the individual, which connects the voter more directly to the responsibility of the party and the government. This is reinforced by the list and proportional representation system. A similar system of strict party discipline existed in the United States until 1969, when a reformed pre-election system was introduced to limit the control of so-called party bosses. It is true that the German system is not ideal and most institutions that receive public moneyhas led to the spread of party patronage, but that seems a price worth paying compared to a political Wild West that favors big bucks and extremist candidates.

An open electoral system and high voter turnout:

In the federal elections in September *, voter turnout in Germany was almost 77 percent, compared to 67 percent in the US elections in 2020 *, which was high by US standards. All eligible voters are automatically registered in Germany when they take up residence in a municipality, and every eligible voter receives a reminder with instructions by post. As in many other democracies, elections take place on Sundays, when only a few citizens have to take time off from work. Postal voting is unproblematic, around 40 percent of Germans voted by post this year.

The idea of a democracy that defends itself:

The willingness of Germans to actively defend democracy is also a lesson for Americans. Given their historical experience with the fragility of democracy, there are a number of proactive measures to combat and ban anti-democratic parties and political hate speech. These were used in the past against the Communist Party and neo-Nazi groups and hang over the head of the right-wing party Alternative for Germany * (AfD), which received only 10.3 percent of the vote in the federal election, 2.3 percentage points less than at last election in 2017.

Anti-democratic disinformation on social media is also subject to certain restrictions.

In addition, most Germans still rely on television and other traditional media for their political information.

The concept of free expression in Germany really does refer to responsible free expression and efforts to spread disinformation or undermine democracy will not be tolerated.

This explains why the Russian attempts at disinformation, which primarily support the AfD, had only a very limited impact outside of the small ecosystem of Russian and pro-Russian media.

A limited national security state:

The January 6 * Washington uprising made it clear to everyone that there is a group of discontented former and active members of the military and police in the United States, many of whom are well armed, which parallels the Weimar experience Represents republic with the murderous volunteer corps and other estranged veterans of the First World War. While today's Germany is often criticized for neglecting defense, the lack of a large armed force, national security apparatus and militarized police force has proven to be an advantage for democracy. However, the abolition of conscription a decade ago has increased the threat of a more isolated, self-choosing, and radical army.

A social market economy:

Although social and economic inequality is increasing in Germany, the level is still low compared to the United States. Germany has a social system, the main features of which arose in the 19th century and which benefits everyone, including the middle class. There is also a strong sense of social solidarity. The Germans describe their system as a “social market economy”, in which both conservative and socialist traditions are united.

German unification brought 17 million East Germans into the nation, who were socialized in a communist planned economy and strengthened the social dimension of political culture. Germans have a concept of positive freedom, which states that the state plays an important positive role in maintaining social equality and cohesion. The state must guarantee an extensive social network of institutions and measures to protect the individual from so-called jungle capitalism and the clash of socio-economic interests.

As a result, wealth in German society is much more evenly distributed: In 2017, the Gini index for income inequality (0 stands for complete equality and 1 for complete inequality) in Germany was 0.29, while in the United States was 0.39. The United States was 39th in the world for the poverty gap and Germany 144th. The decline of unions in the United States contrasts with the role of unions in Germany, whose participation in collective bargaining and corporate governance is enshrined in law. Its members sit on every supervisory board of a listed company, for example.

Confronting the Past:

Both the United States and Germany have a terrible racist legacy, but Germans have bravely faced their Nazi past. The most striking symbol for this is a large and impressive Holocaust memorial in the center of Berlin. Americans are only now starting to grapple with the legacy and history of racism, but unlike Germany, this is just another politically polarizing topic.

Most importantly, Germans do not take democracy and an open society for granted. Your experience of the alternatives - the two great totalitarian ideologies that caused so much suffering and death in the 20th century - is still too fresh. Americans have become complacent because they have lived with some form of democracy for over 200 years. Americans still suffer from the hubris of exceptionalism, something that Germans avoid.

German democracy has its shortcomings. The emphasis on consensus means that reforms are difficult. The change is clearly gradual. Regulations and red tape can be overwhelming. The split between the new federal states - where the AfD is strongest - and the western federal states is a variant of the split between Republicans and Democrats in the United States. Also because its system blocks so many changes, Germany has fallen behind in key areas of digital technology that are crucial for its future competitiveness.

With the emergence of a six-party system, it will be the first time in recent history that three parties will form a coalition government, which is sure to test them.

But these are problems and imperfections that most Americans would trade for the problems they are currently facing.

Americans can be proud of having helped build democracy in Germany, but they could do worse than learn from that success.

by Stephen F. Szabo

Stephen F. Szabo

is Associate Professor of German and European Studies at Georgetown University and Senior Fellow at the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies.

This article was first published in English on October 17, 2021 in the magazine "ForeignPolicy.com" - as part of a cooperation, it is now also available in translation to readers of the IPPEN.MEDIA portals. * Merkur.de is an offer from IPPEN.MEDIA.

+

Foreign Policy Logo

© ForeignPolicy.com