On January 21 this year, four days after celebrating his 101st birthday, Bernard Papenk died at a hospital in Sniča, Slovakia, from a complication caused by the corona virus.

His body was buried in a local cemetery.

Until his death, Pappank was considered the last remnant of the Czechoslovak fighters who took part in the heroic battles against the Nazis in World War II in Tobruk in Libya and in Dunkirk, France.

The news of the death of the quiet old man, who lived in his last years in a small Slovak village not far from the border with Austria and the Czech Republic, did not resonate in the country.

In fact, it is doubtful if anyone noticed her in the flow of events.

But in Slovakia and the Czech Republic, the news of his death became known almost everywhere.

Slovak Defense Minister Jaroslav Nad even greeted him warmly: "A man with a huge heart for justice, freedom and the Slovak people has left us. Bernard Papank was an extraordinary man, whom I personally had the privilege of meeting and thanking on behalf of the Slovak Republic for strength, sacrifice and respect. Which he brought to his country during the struggle against Nazi rule. "

In contrast, his honor was won in his country, the veterans of historians in Israel, and the elders of Kibbutz Yagur at the foot of the Carmel, remember Papank in a different historical context, and in a much more controversial light.

The reason: his name is associated, not in his favor, with one of the most constitutive and infamous events in the history of the Jewish community in Eretz Israel, an event that the scar he left did not heal even after seven and a half decades.

The event in question was a large-scale military operation conducted by the British Mandate authorities in June 1946, in an attempt to eradicate the Jewish underground movements, which were fighting for the establishment of the State of Israel.

The British called the operation "Broadside", but in the Hebrew national memory it was established by a much more dramatic name: "Black Sabbath".

Due to a series of coincidences and misinterpretations, Pappank is suspected of allegedly informing the British army about the presence of hidden weapons in Kibbutz Yagur.

He was abducted, tortured and interrogated by members of the underground, charged with treason, and the defense organization, he said, even imposed a death sentence on his head.

Only two years later was his name cleared of suspicions against him, but the purge never received an official stamp.

Until the day he died, Pappank still expected the long-awaited moment to come, and not with a weak apology.

"Papank never talked about what happened there, that Black Saturday," Givona Alexandroni, his niece, who lives in the center of the country, said this week.

"He preferred to live his life quietly."

Alexandroni asked not to speak, and just put on the table a file laden with documents left behind by her father, the late Israel Pelgi, the younger brother of Papank. Pelgi, who died in 2007 at the age of 83, was for years a senior official in the Ministry of Transport Officially the name of his brother, and his daughter left the archival material he collected, in case the question arises again: What really happened that fateful Saturday?

For the Hebrew rebel movement, the umbrella organization of the underground that fought against the British, the Sabbath of June 29, 1946 was an almost fatal blow.

4,000 soldiers from the British Air Force's Airborne Sixth Division surrounded Kibbutz Yagur, in addition to many other cities and towns throughout the country, and for about a week conducted intensive searches for underground personnel and weapons.

In Kibbutz Yagur, the searchers managed to find 33 hidden slicks, in which, among other things, 325 rifles, 96 mortars, 78 pistols, 425,000 bullets, 5,000 grenades and 5,200 mortar bombs were hidden.

How did they know to accurately locate the hiding places?

It is this historical perplexity that has formed the basis of false suspicions against Papenk.

Bernard Papenk was born in Vienna, Austria, as a preterm infant weighing less than two kilograms.

The doctors warned his parents not to survive and advised his mother not to make any contact with him.

But it was a negligible obstacle in the course of his life, full of upheavals of those who would live for a whole century - and another year.

After his brother Israel was born, in 1923, the Papank family decided to return to their homeland, in the Moravian region of eastern Czechoslovakia.

Bernard went to Vienna again to study business administration, but returned after the Nazis invaded Austria in March 1938. Realizing that the Germans were biting more and more parts of Czechoslovakia, just before World War II, he was assisted by a wealthy businessman and immigrated to Israel at the end of that year. .

He lived in Kibbutz Yagur and worked as a baker.

In fact, Pappank wanted to help in the fighting and not bake breads.

At first he wanted to be a notary (a Jewish policeman in the British police), but due to a poor health condition it was decided to give up his services.

Just before he said desperate, he acceded to the public request of the exiled Czech prime minister, Edward Banesh, who in the early 1940s called on young Czechs to join the combat units from his country, which had teamed up with European allies in the war against the Nazis.

Papank found himself in the 11th Battalion of the Czechoslovak Army, under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Karl Klaplek.

In 1942, as a private, he operated Beaufort anti-aircraft guns near the Libyan city of Tobruk, where the Allies tried to repel the forces of the German "desert fox", General Field Marshal Erwin Rommel.

In September 1944, he participated, with the Czech force, in assisting a Canadian infantry brigade in the siege of the French port city of Dunkirk, which was held by 12,000 German soldiers. The siege lasted eight months, almost until the end of World War II, but for the Jewish soldier Mortar, it ended on December 19, due to a severe gunshot wound.

Papenk's friends rushed him to a nearby Canadian field hospital.

He was operated on for eight hours in his abdomen, and the doctor later said that fortunately he had penicillin on hand and reasonable sanitary conditions for surgery, otherwise the soldier would not have survived.

After recovering, Pappank was flown to England.

Knowing that his parents had been murdered in the extermination camps, he preferred to immigrate to Eretz Israel again, where his younger brother, Israel, who immigrated himself in 1940, lived.

This time he rented a room on Ha'amal Street in Haifa and invited Otto Freund, himself a Jewish soldier from the Czech forces, as a partner.

• • •

Six weeks after finding his place in Haifa, Pappank planned to spend a relaxing weekend with his friends at Kibbutz Yagur.

He arrived at the kibbutz on Friday, June 28, 1946, in the afternoon, one day before the British raid on the place.

Due to intelligence information, members of the kibbutz knew in advance about the British operation.

"We had a meeting on Friday night, and everyone was invited to come," recalls the kibbutz member, Rachel Tepper (91).

"I was a student at the end of ninth grade at the time, and we were divided into roles: 'You stand by that gate, you by that gate.' The preparation was very organized."

At the entrance gates to the kibbutz, agricultural tools were placed, and next to them stood the members, who were asked to express a gentle protest and not to surf into a violent confrontation in front of thousands of armed and trained British paratroopers.

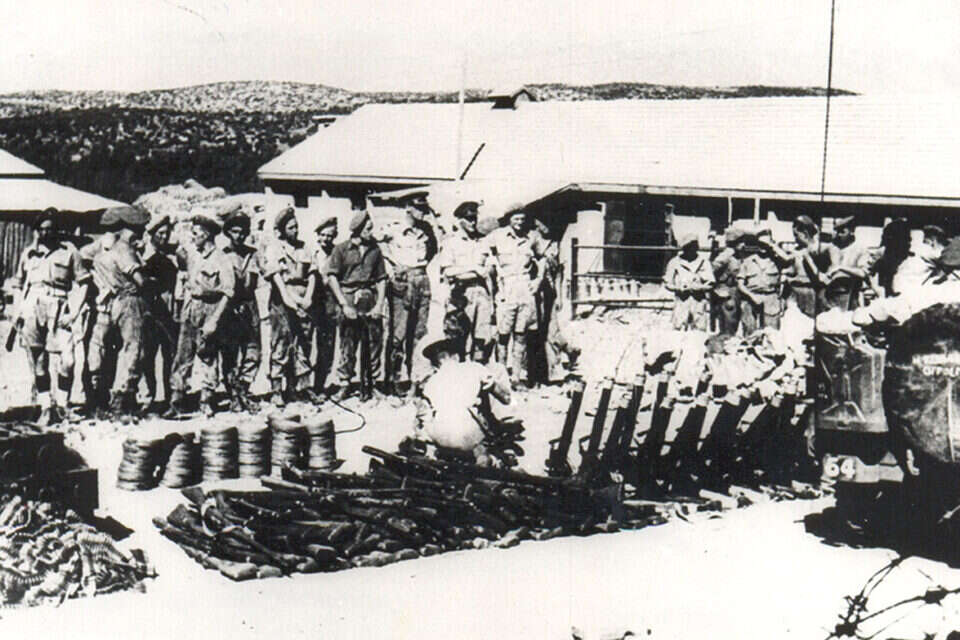

British soldiers use metal detectors to locate weapons of mass destruction.

"See Papenk talking to a British officer, and immediately released", Photo: Yagur Archive

"The British arrived in the morning and surrounded the kibbutz from all directions. They gathered all the members, and with the help of shotguns brought them into the dining room," says Yagur's friend, Amitai Agmon (83).

"During the takeover, they threw tear gas grenades and sprayed machine oil mixed with diesel. The walls absorbed the material, which we have been stinking for decades."

Papank, who was sleeping in one of the rooms at the time, was unaware of the drama going on outside.

When he finally left, a British soldier asked him who he was and what he was doing on the kibbutz.

Papank later said that he did not know about the instruction given to members to identify themselves as Jews from Eretz Israel, so he told the British that he was a Czech soldier, and even presented them with documents proving this.

The British realized that this was a friend who had recently fought alongside them and released him on his way - unlike the rest, who were concentrated in one place.

This turn will later turn out to be a very crucial detail regarding the suspicions against him.

• • •

The British searched for weapons in the kibbutz, and for long hours found nothing.

On Sunday, at two o'clock, when they were about to leave, a British soldier suddenly arrived and told of an interesting find: as he knocked on the floor of the dining room he heard a sound heralding an underground space.

The British hurried to lift the floors of the dining room, and soon got on a slick where 19 pistols and quite a few mortar shells were hidden.

At the same time, to the left of the entrance to the farm, near a pool of water, the soldiers dug and found more weapons.

A British soldier also found a barrel in which ammunition was hidden.

"In Slick, there is a need for ventilation for weapons, and one of the patents was to create slicks with ventilation pipes above them," says the kibbutz member, Yotam Vardi (84).

"The British realized that every slick had such a pipe, and started looking for pipes throughout the kibbutz. And so, instead of one day, they stayed with us for seven days."

Researchers from the Defense Organization, which examined the activities of the British Bigor, later compiled a report, which is also among the papers of Israel, Papenk's brother. One of the researchers wrote in the report: " The warehouses. Their work was accompanied by exceptional experts and proficient. "

The men of the kibbutz, as well as some of the women, were taken for questioning in detention camps in Latrun and Rafah.

They stayed there for many months.

Tepper: "I will not forget that at the end of the search, the British deployed a room-sized tarpaulin and put all the weapons they found on it. All day long, there were processions of soldiers in the kibbutz who came to see the findings."

In the meantime, Pappank returned to Haifa, and three days later there were loud knocks on the door of his rented apartment.

When he opened, three masked men, the defense men, rushed in and forcibly took him and his roommate - Otto Freund.

It turned out that when members of the Haganah, the defense service of the Haganah, asked the kibbutz members, one of the companies that saw Pefank "talked to a British officer and was immediately released" - in contrast to the other kibbutz members held under guard.

Agmon: "We did not believe that the English would be smart enough to discover the Slick, and if they found out - a sign that they had information. The company told what they saw, and just did one and another. "I wanted to know then what 'traitor' looks like. I have to say that the traitor looks to me like a person from the locality."

Papank later told British police about his abduction.

"On the first day I was led in a car with my eyes closed. I felt like we were going up a mountain, and that the road passed through trees. I was put in a small room with an iron door. A thin, tall guy appeared there, who started beating me. From a cafe, because I heard the sound of an orchestra playing. "

Pappank was taken to an apartment on Haneviim Street in Haifa, where he was tortured by his captors in an attempt to extract information or a confession from him that he was the informant.

He arrived at the British with his body full of burn marks from burning cigarettes, and his penis was also injured.

Freund, his roommate who was arrested along with him, also answers, but investigators concluded he did not stay in Bigur that Saturday at all.

He won, enlisted in the IDF, served in the Golani, but later said that "he never regained his composure." Died in Haifa in 1979, at the age of 64.

For 11 days Pepenk was imprisoned in the interrogation apartment, insisting that these were false accusations against him.

The defense personnel were not convinced, and at one point it was even reported that he was sentenced to death.

But the Czech soldier, whose life story could support a Hollywood script, managed to escape from the house where he was being held.

He also told the British police about this, as detailed in the documents left by his brother, Israel.

"Last night they started beating me again," Papank told the FBI.

"I defended myself as much as I could. There was a window, and I hit my leg and hand until it broke - and so I managed to jump. Not far away was Wadi, and I ran to him. From there I ran until I reached the main road. A car stopped at my request drove me to the nearest police station."

Due to his injuries, Pappank was hospitalized in a government hospital, in a ward where mostly British soldiers were treated.

A double guard was placed on his room: a British soldier armed with a submachine gun and an Arab policeman.

He later said that the severe torture he endured did not break his spirit, but rather the publications about him in the press in those days.

Among other things, his mother was described as a Christian, even though in practice she was a Jew who perished in Auschwitz.

Elsewhere it is written that he was a British agent.

"The newspapers are the ones who killed me. I felt I was broken and I had no more strength," he said years later.

During the abduction of Pappank and Freund, quite a few false rumors about their fate were circulated to the public, including reports of their alleged execution.

Finally, it was reported that Pappank was put on trial, but "enjoyed the doubt and it was decided to deport him from the country."

The late Papank, in a photo from a few years ago, Photo: Deník / Petr Turek

Either way, the defense was unable to substantiate the suspicion against him, and although she admitted he was innocent - she never officially stated it.

David Shaltiel, who headed the organization's intelligence services, was quoted in the newspaper "Davar" on July 23, 1948 as saying, casually: He fled the day before. "

Hillel Levitan (80), a friend of Yagur: "I once asked the late Meir Pa'il, who was a historian and Palmach, what do we know about the story we had. There was no information. "

But does the myth still exist?

"To myths living their own."

Immediately after recovering from the abduction, the British took Pappenek by train to Egypt, from where he took off for Vienna and proceeded to the Czech Republic.

There he began working as a language teacher, as a construction worker and as a clerk.

During the years during which the British had already left the Land of Israel, he did not stop believing that justice had not been done to him.

He wanted his name to be cleared - a hope that took on a new meaning after the State of Israel was established.

On February 12, 1952, Papank wrote a letter from his seat in Brno, Czechoslovakia, to Justice Minister Dov Yosef.

"My brother, Israel, was promised a new inquiry into my affairs after the establishment of the Hebrew state. Nevertheless, my brother did not succeed, because there are a number of people in important places who do everything not to allow a new inquiry. I allow myself to address you, Mr. Minister, And in the name of the honor of my family and myself, please clarify this whole matter in the near future. "

The inquiry to which Pappank wished most of all - did not take place.

• • •

It is possible that at that point his ties with Israel would have ended in thunderous anger, but starting in 1948, after the National Assembly in Czechoslovakia approved a new constitution that relied on the Communist Party's guidelines, Pappank felt "watched over" - and said Czech security organizations were harassing To him being a Jew.

In 1961 he married Edith, who had raised a son and a daughter from a first marriage, and at the first opportunity that came their way, when he received a short residence visa in Vienna, he offered his wife to take advantage of the window of opportunity - and immigrate to Israel.

The two children, aged 16 and 18, were left behind, hoping to join later.

In the summer of 1964, the small family landed in the Bat Yam transit camp and lived in hut 218, in asbestos.

At that point Papenk changed his name, and is now called Benjamin Pelgi.

His previous name no longer appeared on his mailbox, in an attempt to open a new and clean page in his life (he himself explained to the questioners that "it is difficult for Israelis to pronounce 'pfank'").

The Israeli media, as usual, quickly surpassed his identity and demanded answers from him, more than 18 years after "Black Sabbath."

Palgi decided to put an end to the issue, once and for all, and convened a press conference in his hut.

But here, too, the drama did not end: just before he began to speak, there was a sudden knock on the door, and a policeman at the door asked him to accompany him to the police station.

It soon became clear that one of the neighbors recognized the faction as a "traitor for once" - and hurried to turn it over to law enforcement.

At the station, the police realized the mistake, and released the stunned factions, who returned home by bus.

There the journalists were still waiting for him, who wanted to hear his version.

"I did not give the British information about the Bigor weapons depot," he told them.

"I never knew where the weapons were. I have now returned to Israel, because I have always been a national Jew. That is why I immigrated to Israel as a teenager, and that is why I waited 18 years in the Czech Republic for the day when I can return to Israel. "In 1948, it was a tragic mistake that forced me to leave the country. I do not want compensation, I do not want anything. Leave me alone, let me just live in peace."

Rachel Tepper, Yotam Vardi and Hillel Levitan in the central Slick in Yagur, which became a heritage museum.

"We did not believe that the English would be smart enough to find out," Photo: Michael Giladi, Ginny

From that day on, Benjamin Pelgi disappeared into the alleys of oblivion.

He lives in Bat Yam and as usual moved between jobs.

In the Czech Republic, it is written about him that he worked for a certain period at El Al.

He and Edith had no children, and her children from her first marriage eventually remained in Czechoslovakia.

Givona, his niece, says that despite the difficulties, her aunt never lost his optimism and joy of life.

"He was a very intelligent, optimistic and pleasant-mannered man. If things had bothered him, I do not think he would have lived so many years."

Edith passed away in the early 2000s, after a serious illness.

Realizing that he was left in the country without a close family, Pelgi decided in a surprising move, at the age of 94, to move to Saidikov Humantsa, a small village in Slovakia on the banks of the Banski River.

A settlement next to a large forest, with a church in the center.

He moved there mainly because Vieira, the daughter of his late wife, lives there.

In the village, where about a thousand residents live, they soon began to get to know the amiable old man who came from Israel.

Pelgi spoke cordially with everyone, used to feed the stray cats, and the local pastor also enjoyed hearing "stories from the past" from him.

At the age of 100 he still went for walks in the nearby forest, without the aid of a cane or escorts, and according to his neighbors was still razor sharp.

Local military historians, who delve into the history of the Czech army, were astonished to discover in the archive records his name as one of the hundreds of Czech soldiers who participated in the 1942 defense of the city of Tobruk in Libya.

Due to his extreme age, he was immediately crowned as the last remnant of those battles, and to the delight of the country’s media, he remembered the events well.

Until his arrival, another 97-year-old soldier was considered the last survivor of those days.

The Slovaks hurried to give the veteran a victory medal and adorned it with countless articles on television and in the press, in which he recounted the heroic battles and his severe injury in the fighting against the Nazis.

"I think they are interested in me because I am the oldest soldier from there," he said in an interview with Slovak radio.

"I myself am not an important person."

When Bernard Papenk passed away, he was Benjamin Pelgi, as a war hero.

Czech television reported "the death of the last Czech witness to the battles in Tobruk and Dunkirk", but even among the mountains of words spilled in his memory, not a single word was mentioned of the trauma he experienced in the summer of 1946, in Israel.

"Yagur has preserved its slick as a heritage site," says Anat Ogen, a member of the kibbutz and director of the "Yagur Track" - which monitors the local heritage sites.

"Thanks to the 'Palmach' series, which was televised with all the big youth stars, and thanks to Galila Ron Feder-Amit's book 'The Time Tunnel - The Black Sabbath,' many families with children interested in that period began to come here. They ask us, 'Was there an informant?'

And we say no. "

The site at Kibbutz Yagur is part of "Heritage Week" - a collaboration between the Ministry of Heritage and Jerusalem, the Council for the Preservation of Heritage Sites, the Nature and Parks Authority, the Antiquities Authority, the National Library and Yad Ben-Zvi, to get to know the heritage in Israel, from north to south. Heritage Week will include hundreds of activities at dozens of sites throughout the days of Hanukkah, from November 29 to December 6. The full program at moreshetonline.org.il

shishabat@israelhayom.co.il

Were we wrong?

Fixed!

If you find an error in the article, we will be happy for you to share it with us and we will correct it