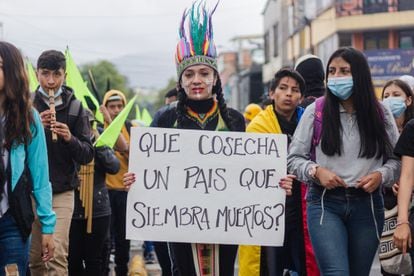

A woman holds a sign during a protest in Nariño, Colombia, on June 28, 2021.Sebastian Maya (Getty Images)

Only 11 days in January had passed and two massacres had already been recorded in Colombia. In all of 2021 there have been 94 with more than 300 victims. The last occurred on the night of December 26 in Casanare, in the eastern part of the country. Three peasants, members of the same family, were shot near their home. Just hours earlier, in a nearby region, another massacre left four wounded and three dead. The previous afternoon, the 25th, an armed group broke into an indigenous reservation in Putumayo and murdered seven people. The community reports that there are as many missing persons and that 35 families were forced to displace. Five years after the agreement with the FARC, Colombia still does not live in peace.

Since the signing in 2016, between 4,000 and 6,000 lives of former guerrillas, public forces and civilians have been saved, according to Cerac, a conflict research center that monitors acts of violence in the country. About 13,000 guerrillas demobilized and rejoined civilian life. The agreement has worked, but not entirely because its implementation has been incomplete. “There is an increase in indicators of violence such as massacres, homicides, forced displacement, which can be explained by a combination of factors: a bad government security policy, slow implementation of the peace agreement and the pandemic, which gave it a opportunity for armed groups to expand, ”says Juan Pappier, Human Rights Watch (HRW) researcher for America."2021 will probably be the year with the highest homicide rate per 100,000 inhabitants in Colombia since 2014," Pappier has warned in recent days. According to the Defense Ministry, until last November there were 12,787 homicides. For seven years there was no similar figure. In 2014, the closest was 12,060.

"The peace agreement has a clear component to confront the violence of the groups that would be formed after the demobilization of the guerrillas, but this has been forgotten by the government," adds the HRW researcher. It refers to points 3 and 4 that speak of the State's obligation to offer guarantees for the reintegration of the demobilized, to generate a policy to confront other armed groups and to change drug policy to favor those who have been affected for decades. for illicit crops. Colombia is not the same as it was before 2016, but the way the government deals with crime seems the same, says the researcher.

“The panorama was different. The country was experiencing an armed conflict dominated by the FARC, with a clear structure and ideology. That no longer exists, there are at least 30 dissidents, in addition to the ELN guerrilla and other groups. All, contesting the illegal economies before a government that has not understood that the dynamics have changed, "he says. President Iván Duque has tried to repeat the “strong hand” speech of his mentor Álvaro Uribe, but hitting the heads of the armed structures has not been enough to stop the war. Two months ago, the Government celebrated the capture of Dairo Antonio Úsuga, alias

Otoniel

, as the "most important coup of this century against drug trafficking."

Later the capo, who had under his command about 3,000 men, said that he had agreed to his surrender, something that the Government has denied.

In the areas where the Clan del Golfo operates, the structure that it led, the violence does not end.

That same armed group was responsible for one of the largest mass displacements this year.

In Ituango, in northern Antioquia, at least 4,000 indigenous people and peasants were forced to flee.

"This responds to some dynamics of old actors with new names, but with the same objectives that the groups pursued in the 50s, 80s and 90s: control and appropriation of the territory," the sociologist Nubia explained when the news broke. Ciro, in an interview with the University of Antioquia.

Carlos Medina Gallego, professor and member of the National University's Center for Thought and Follow-up to the Peace Dialogue, says that there is a simulation by the Government regarding the implementation of the agreement. “There is no true peace policy. The discourse continues to be that of security policy that only points to war, ”says the academic. "The Government is not interested in complying with the agreement and has been more concerned with showing a repressive policy and talking about a war against drug trafficking, which seems to only be simulating," says Medina Gallego.

According to the United Nations Office of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), until last October there were 136 massive displacements in Colombia. Entire families were harassed by violence and had to leave their homes. The victims remain the same: indigenous and Afro-Colombian. “The greatest threat has been stigmatization, the denial of the importance of peace and the implementation of agreements as a priority. Not only social leaders face death because there are armed groups in their territories, but also because there are alliances that do not want to accept the transition from war to peace, the transition to the post-conflict, ”explained Camilo González, president of Indepaz, in a video about violence in Colombia. This year alone, 168 social leaders and 48 signatories of the agreement were assassinated. They go more than 1.200 since the signing in 2016. Although at least 95% of former FARC guerrillas are complying with the peace process, the slow implementation of the agreement has left them in the midst of a dispute between armed groups that threaten their lives. .

The cities, another front to attend

If in the regions peace does not finish arriving;

in cities, life is not quiet either.

In large capitals, taking a cell phone out on the street means putting your life at risk.

Last week, reality again showed that it is not just a matter of perception as local leaders try to show.

Natalia Castillo, a 32-year-old journalist linked to the UN office in Bogotá, was the latest victim of insecurity that the mayor, Claudia López, has been unable to tackle. The woman was murdered on the night of December 23 in the street in an attempt to steal her cell phone. The crime occurred a few weeks after the announcement by the national government of a reinforcement of more than 1,000 police officers with which the Executive hoped to reduce the rates of violence in urban areas. But crime, which ends up taking lives, not only needs uniforms to confront it. The analyst and professor Carlos Medina Gallego points out several factors that must be addressed as a priority: poverty, unemployment, migration. Colombia has been a country with open doors to Venezuelan migrants,but with few possibilities for them to lead a decent life with a formal job and the social benefits that this entails. According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), Colombia closes the year with more than three million people looking for work.

The solution to violence not only involves the police presence, whose image this year ends up deteriorating.

The UN confirmed just a few days ago the responsibility of the police in the murder of at least 28 people during the protests against the government of Iván Duque.

The same entity had confirmed days before the murder of 11 young people, also at the hands of the police.

Subscribe here to the

EL PAÍS América

newsletter

and receive all the informative keys of the act