Memory is something fragile, capricious, necessary.

Elías Barahona thought that the best secret was the one that was never revealed.

And for decades, silence and oblivion were their main weapons of survival.

But there are stories that deserve to be told.

That even if they are buried in old files and their traces are tried to be erased, sooner or later they end up coming to light.

It is 1980, in the middle of the civil war in Guatemala. A crowd of indigenous leaders, peasants and students take over the Spanish Embassy to protest the massacres committed by the Army. The police burst into the place. With blood and fire, but in the most literal and painful sense of the word: they cause a fire in which 37 people die burned. The only surviving social leader is kidnapped from the hospital and murdered the next day. Barahona was an eyewitness inside the government offices that day.

34 years later, on October 2, 2014, a man in a wheelchair with a pale blue shirt, gray hair and wide glasses takes an oath in front of a court in Guatemala that judges the events of that day, one of the worst massacres of the country's history.

This is Barahona, alias

El Topo

.

Behind, a young woman, Anaïs Taracena, a personal friend of Barahona and a budding filmmaker, documents everything with a camera.

That same day, she records an interview with him at his home.

Two weeks later,

The Topo

dies.

At that moment Taracena decides to recover the incredible story of her friend, which in 2021 became a documentary:

The silence of the mole

.

Barahona was a teacher, journalist and poet. And even before that, he was a collaborator with the Guerrilla Army of the Poor, a leftist insurgent organization in Guatemala. He achieved what seemed impossible: he infiltrated the Government as press chief for Donaldo Álvarez Ruiz, the Minister of the Interior during the regime of General Fernando Romeo Lucas García (1978-1982), predecessor of the dictator José Efraín Ríos Montt and designated as one of the those most responsible for human rights violations in Guatemala. Álvarez Ruiz is today wanted and captured, considered a war criminal guilty of massacres and the most brutal repression during those years. From within,

El Topo

He managed to find out which political dissidents, activists or guerrillas were in his target and warned them of the danger they were running so that they could flee the country.

Like a Guatemalan version of Oskar Schindler, the Austrian businessman affiliated with the Nazi party who managed to save more than a thousand Jews from the Holocaust.

The team during the filming of the documentary 'The silence of the mole'EL SILENCIO DEL TOPO

“Between 1980 and 1983 are the bloodiest years. It is believed that it was only during the Ríos Montt period, but he gives continuity to what Lucas García and Donaldo Álvarez Ruiz were already doing. They start the scorched earth policies”, explains Anaïs Taracena, one afternoon in December 2021 by video call from Guatemala City. “There are no estimates of how many people Elías saved, but I think there were dozens. It was all very clandestine. It also depended a lot on the interpretation, there were those who saw it as a threat instead of a warning.

His system was complex and intricate.

Sometimes he left a piece of paper stuck to a park bench with the names, which a partner of his picked up.

Other times, he would risk more and sneak it under the door of whoever was at risk.

He tried not to leave a trace of his time in Álvarez Ruiz's cabinet, he did not give statements or allow himself to be photographed.

Still, many of his former colleagues and friends viewed him as a traitor.

And his story fell into oblivion.

Exile

At the beginning of the eighties, the situation became unsustainable and Barahona was forced into exile. Recently divorced, he had obtained custody of his daughters, aged 12 and 15 at the time. “He told us that his life was in danger, and if we wanted to go with him or stay. We were very attached to him and decided to leave,” says the little girl, Paty, now 54 years old. For 16 years they moved throughout Central America. Hotels, shelters, houses of friends and fellow exiles.

“There was a wave of repression, the eighties was a time of bloodshed in Guatemala. Many people died, journalists, students were murdered, and of course, you, as a child, do not fully understand what is happening, but you see that there is a lot of danger. It was quite hard and sad, as if you had totally lost your family without knowing until when, we could not have communication. I was a little scared. But we trusted him a lot”, synthesizes Paty.

They lived for a long time in Nicaragua, a country excited by the promises of the Sandinista revolution, the perfect place at that time for

El Topo

.

“My father was a correspondent for foreign media.

I always remember him very thoughtful and tense”, he recalls.

The two sisters knew something was up, but it was not until years later that they began to understand what he had done in Guatemala, based on press articles or the statements he gave.

At home, he hardly spoke.

"I didn't want to put anyone at risk."

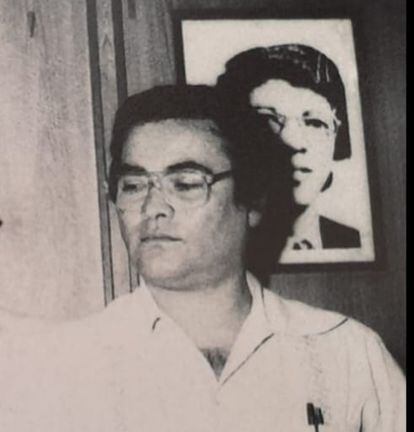

Elías Barahona, in the foreground.

Behind, a portrait of the journalist 'Maco' Cacao, assassinated by the military in 1980. GUILLERMO CACAO

Barahona was the son of a very poor peasant family, "who went hungry and that marked him," according to his daughter.

He spoke to them about injustice, inequality and poverty.

“He was always consistent with his ideas.

In his terminal stage he wanted to testify in the trial of the Embassy of Spain.

I told him no, that it was very bad, but he replied that it was his duty and his obligation.

I was cold because I thought I was not going to hold out.

The following month he passed away, and yet he was adamant about giving that information.”

The silence of the mole

The filmmaker Taracena was closely involved in the subject. Her father, a Guatemalan historian, also had to go into exile in the 1980s. She grew up in Costa Rica and later got a scholarship to study Political Science in France, her mother's country. There he met David Barahona, Elías's brother. “There was a group of Guatemalan exiles who had stayed in France, and I knew them all. I wanted to do something audiovisual and I filmed David. I made a short film called

De guts corazón

[2011]”. He put him in contact with Elías when Taracena returned to Guatemala. Little by little they became friends and one day she asked him to record an interview.

“Elías was not an easy person at all, you really had to be very confident to be able to talk about it. All his life taking care of what to say”, he recalls. Taracena was particularly struck by Barahona's profile: "He is not the typical person that the left claims: he was not a commander, he was not someone who took up arms or went to the mountains, he collaborated from his position as a journalist and had that infiltrate work. In fact, there were many people like him. That is almost never talked about and they are people who risked their lives.”

Making the documentary became an odyssey.

When he began to delve into the archives, he found that hardly any material was preserved in the newspaper archives recorded between 1980 and 1985, the years of main repression.

The documents had been lost, or someone had deleted them.

He spent hours poking around, trying to find videos and photos in which Barahona or Donaldo Álvarez Ruiz appeared.

It was almost a craft job.

reunions

One of the events that caused

El Topo

to go into exile was the assassination at the hands of the military of journalist Marco Antonio

Maco

Cacao, a close friend, on July 5, 1980. That always weighed heavily on his memory. So much so that on July 20, 2009 he wrote a tribute to him on a blog. Thirty-one years and one day after that death, on July 6, 2011, Guillermo Cacao,

Maco

's son , came across Barahona's words while searching for his father on the internet.

“My dad and Elías were great friends, we used to go to meetings at his house,” says Cacao by phone from Guatemala. “I remember Elías little. When my father was murdered, I was 7 years old, but his name was in the house, in the mind. When I saw the blog I wrote to him, but he never answered me”. Guillermo, his brothers and his mother also went into exile, threatened. Taracena contacted him when he started making the film. “Elías's name

clicks

again in my head. She had interviewed Elías's daughter, Paty, and she told him about my dad. I had never heard from them again, but she is older than me and remembers a lot about the meetings. He found me on social media and we started talking."

Marco Antonio 'Maco' Cacao interviews Donaldo Álvarez Ruiz, the Minister of the Interior between 1978-1982), in a file image.Guillermo Cacao

Cacao agreed to participate in the documentary: “Losing my father was the most painful thing I've ever had in my life, but I want the people who used State resources to murder people to be pointed out.

It is not pleasant, they are not pretty stories, but the past made us who we are.

The documentary is very important to maintain the historical memory of this country.

The new generations do not know what happened,” he says.

Important and dangerous. So much so that it has not yet been released in Guatemala, where the director plans to rent a movie theater and organize a private screening. Nor can it be viewed freely on the internet. It has only been presented at festivals. There is still a lot of fear of possible reprisals, explain all those interviewed. And, above all, to a proper name: Donaldo Álvarez Ruiz, who is still free and a fugitive from justice, who is looking for him for crimes against humanity.

“Some people say that he is in the United States,” explains Paty. “Knowing that he died is not the same as knowing that he has a lot of family in Guatemala and that he can still cause harm. Many of the things that happened were led by him. Many times you don't have a

chance

to speak and suddenly you woke up dead and you don't know what happened. That is why sometimes people are silent, there is still fear.

The data proves him right.

Between 1960 and 1996, more than 200,000 people were killed and 45,000 disappeared in Guatemala, according to the Historical Clarification Report, which showed that 93% of war crimes were committed by the Army.

Many of them were condemned to oblivion.

Now a documentary that recovers the life of a man who was actually a mole has arrived to open cracks in the silence.

Subscribe here to the EL PAÍS América newsletter and receive all the key information on current affairs in the region