The lies began soon. Two weeks after 9/11, Donald Rumsfeld was asked by a reporter at the Pentagon if he contemplated spreading falsehoods in the media about military operations in the newly launched Afghanistan campaign in order to confuse the enemy. The old hawk, Secretary of Defense with Gerald Ford and with Bush Jr., quoted Churchill ("In war, the truth is so precious that it must always be protected with a train of lies"), unsheathed one of his ironic smiles and shot: “The answer is no. I can't imagine that happening."

But it happened.

And not just that time.

That was the first stone of a building of lies built for almost 20 years.

A building that reached one of its highest heights at the end of 2014, when Barack Obama, knowing that it was not true, declared: “Our combat mission in Afghanistan is ending, and the longest war in American history is drawing to a close. responsible end”.

That end was actually made to wait six years and eight months.

And very few would describe the chaotic withdrawal last August ordered by Joe Biden as “responsible”, a decision with devastating consequences for the Central Asian country.

Controlled by the Taliban, who have curtailed the rights of women, Afghanistan looks out this winter to the vertigo of famine.

More information

Afghans fear hunger as much as insecurity

On August 31, the withdrawal deadline, Craig Whitlock published

The Afghanistan Papers. Secret History of the War

(now published by Crítica in Spanish), a book that unmasks these two decades of fallacies. The bulk of his revelations had appeared in 2019 in

The Washington Post,

the newspaper for which this 53-year-old reporter works as an investigative journalist. Whitlock accessed more than 2,000 pages of under-the-radar interviews with 428 people who played a direct role in the war and who spoke openly upon their return from the front lines. The transcripts, public documents not accessible to the public, demonstrated what many, he too, already suspected: that presidents and senior officials of the White House and the Pentagon of three administrations dedicated themselves to misrepresenting, giving false hope and disguising military setbacks. That colonels and ambassadors conspired to cover up the bad news. And that soon the lie became so big that no one dared to retrace his path. Also, that by then, American public opinion,who had almost unanimously supported the decision to go to war among the still smoldering remains of the Twin Towers, was no longer paying attention, fed up with conflicts in places she couldn't even locate on the map.

Reporter Craig Whitlock pictured in Washington. Marvin Joseph (The Washington Post)

"The original sin was going into Afghanistan without a clear plan on how to get out," Whitlock explained Friday at a cafe in Silver Spring, Maryland, effectively a residential suburb of Washington. “They were always vague about what they wanted. If it was a question of ending Al Qaeda, it took six months for the United States to assassinate or expel its leaders from the country, including Bin Laden, who fled to Pakistan. By that time the enemy had already changed: it was the Taliban and other insurgents, those people we didn't quite know what to name but who were shooting at our soldiers. Was it then about ending the Taliban? Or to strengthen the Afghan government and promote democracy? They said we would stay until we were sure there would never be another attack like 9/11. So Bush,Obama and Trump (who arrived convinced of pulling out the troops) lived in fear of being wrong: What if they ordered the withdrawal and then there was an attack? This is how the recipe for an endless war was cooked.

The Afghanistan Papers

interviews

belonged to the Lessons Learned Project, an initiative by an obscure federal agency to try to understand when it all went wrong. Whitlock, who held the defense portfolio at the

Post

, received a tip in 2016 from a source that an agency called the Office of the Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction had questioned

extensively

to Michael Flynn, who commanded the military intelligence of the United States and NATO in the Central Asian country.

Given that Flynn sounded like one of the strong men in Donald Trump's new cabinet (he was his first and short-lived National Security adviser), the journalist thought it would be interesting to hear his unfiltered views on a conflict that, 15 years later, had broken and the marks of a bellicose country.

He requested access to that interview.

And they promised, because, after all, it wasn't classified material.

Then they backed off.

That change of heart made Whitlock suspect that there was an

iceberg

of sensitive information

hiding under Flynn's tip

.

There he began a legal crusade, which included two lawsuits under the Freedom of Information Act, to access those papers.

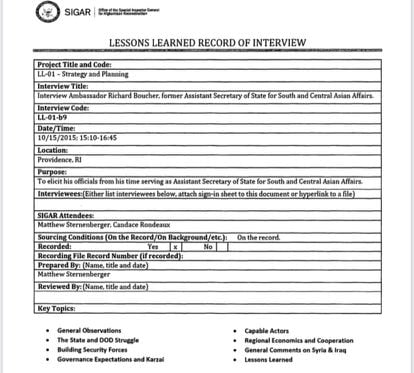

One of the documents in the Afghanistan Papers, corresponding to an interview with Ambassador Richard Boucher.

When he was finally able to dive into them, he compared what those with responsibility had said in public, often in the presence of reporters like himself, in Washington or on the ground, with how they told it to the Lessons Learned tape recorder. Thus, he discovered three-star generals confessing that "at first there was no campaign plan" or the authorities denying that Vice President Dick Cheney was the target of a failed suicide attack at Bagram Air Base in 2007, despite the fact that they had evidence to the contrary. There were voices that soon questioned the viability of creating a democratic government in Afghanistan and even a diplomat, Robert Finn, ambassador in Kabul between 2002 and 2003, who warned about the impossibility of the plan to resolve that mission "in one or two years" ."I told them we'd be lucky if we got out in twenty."

For Whitlock, the value of these documents is "in that the protagonists spoke freely, because their superiors had asked them to do exactly that." “The program started in 2014, when they wanted to think that the end of the war was near, so they tried to be honest about what happened, to draw lessons. When we brought those papers to light, public opinion knew that the generals in charge of the war had no idea what they were doing. And that they had also been unscrupulously lied to," says the journalist, who completed his investigation with oral history interviews commissioned by military, diplomatic and educational establishments, as well as hundreds of memorandums from the Rumsfeld era (2001-2006), brief and forceful documents that in the Department of Defense they knew with the nickname of "snowflakes",by his slow but inexorable way of falling on the tables of his subordinates.

Memo from Donald Rumsfeld sent on September 8, 2003.

The book can also be read as a compendium of political and military impudence that did not understand sides.

“In the first weeks of the war,” recalls Whitlock, “Bush said, 'We've learned our lessons in Vietnam.

We're not going to get stuck like then.'

He also assured that they had studied what the British and Soviets did wrong in Afghanistan, and that the idea would never be to occupy the country with 100,000 soldiers.

That was exactly the number of troops that Obama would end up deploying.

When asked which of the presidents did worse, the reporter did not know how to choose: “They all made fundamental mistakes. Bush was wrong to exclude the Taliban from the Bonn conference [for the future of Afghanistan, held in November 2001] and to write off the 2003 race as won too soon. He was overconfident and afterwards it was difficult to back down. But embarking on the war in Iraq at the same time was surely the worst of his ideas,” he says. “The Obama Administration, which inherited the mess of its predecessor, made a mistake in its strategy of fueling the counterinsurgency. He did not want to see that many Afghans, opposed to the Taliban, also did not like their own government, supported by the Americans, which they considered corrupt. He sent too many soldiers and spent too much money.” And Trump? "He wanted to withdraw the troops,but he soon realized that it was not easy and that he did not want to be the president who lost the war, so he left a much smaller contingent. Fewer Americans died, but things got worse for the Afghans, because the bombing of the population increased.

Whitlock also offers juicy details about the 2011 assassination of bin Laden, President Hamid Karzai ("they put him on because they liked his English and his sophisticated air, but it soon became a problem they didn't know how to solve"), the tensions, sometimes bordering on the absurd, within the allied coalition, the cronyism with the warlords and the mechanisms of corruption in the country, which fueled the US policy of spending without control. “Our biggest project, unfortunately and unintentionally of course, may have been the development of massive corruption,” laments a diplomat in a confession to Lessons Learned. "They were robbing us hand over fist," Flynn says in another interview.

the afghanistan papers

it also contains paths anthologies of euphemism ("We are not losing, but in some areas we are winning more slowly than in others," said David McKiernan, the first general to admit that the war was not going well, shortly before being fired) and nonsense , a mixture of recklessness and ignorance and the result of the misunderstanding of a country in which the United States had not had an Embassy since 1989.

Serve two anecdotes to illustrate it. In 2006, someone thought it was a good idea to give away thousands of soccer balls with verses from the Koran printed on them for propaganda purposes, sparking angry protests: kicking around with the holy words is not usually a good idea in a Muslim country, writes Whitlock. On another occasion, a campaign was designed to improve the hygiene of Afghans. “It was an insult to the people. Here they wash their hands five times a day to pray," Tooryalai Wesa, who was governor of Kandahar province between 2008 and 2015, explained to Lessons Learned. "In his interview," Whitlock added during the talk with EL PAÍS, "the General Flynn was pulling his hair out remembering the case of that high command who learned Pashtun to get assigned to Afghanistan, and, four months after achieving it,They sent him to Japan. It is a prime example of the tyranny of bureaucracy, which encouraged rotation over specialization in the field. It also illustrates the scant interest that many of these soldiers had in understanding the country, let alone in speaking any of its languages.”

Evacuation of civilians at Hamid Karzai International Airport, in Kabul, on August 22, 2021. US MARINES (via REUTERS)

For the reporter, that ignorance still persists. He sets an example himself: he was not surprised that the Taliban took over the country again when Biden announced the withdrawal, but he never thought that it would happen so quickly, “considering all the money that the United States had spent in forming an Afghan army [83,000 million dollars, more than 70,000 million euros, invested in the training of the 300,000 troops]”. "The irony is that Biden agreed with Trump in his desire to end the war," he continues. “I think he knew there was no way to win it. And it ended up creating a terrible chaos. He and his generals thought it would take a few months or a year for the Taliban to return to power. That maybe they would make a deal with [President Ashraf] Ghani and that there would be time to evacuate the Americans and their allies. They could have started earlierbut Biden feared that Afghans would panic. What ended up happening was almost worse. Was there an easy way to end that adventure? No, but surely there wasn't a more disastrous way either."

The journalist has no doubt that "the Taliban, with all their brutality, will control the country for a while, and that Washington must take it on and work from there." “It will be a terrible time, especially for women and religious minorities. I hope there is at least some stability. Afghans are tired of war; They have been in it for 40 years. There is talk going on about how to avoid a horrible famine, and the big question is how to get around economic collapse. The country has been dependent on foreign aid for too long.”

Whitlock put an end to his book in March 2021. For the paperback edition, he plans to add a chapter with what has happened since then.

In the meantime, he tries with

The Washington Post

lawyers to get more papers from Afghanistan, the Lessons Learned interviews after 2018, even knowing that thanks to his efforts the military will now be responding with much more caution.

The precedent of the 'Pentagon Papers'

Daniel Ellsberg, the Pentagon Papers leaker in 1971. BETTMAN ARCHIVE

Craig Whitlock opens his book with a quote from Supreme Court Justice Hugo L. Black, delivered in 1971, during the

Pentagon Papers trial,

in which the high court ruled that the government could not prevent

The New York Times

or

The Washington Post

publish Department of Defense secrets about the Vietnam War, leaked by Daniel Ellsberg. "There are strong similarities and obvious differences between the two cases," says Whitlock

.

"The

Pentagon Papers

they were also the secret history of an American war abroad, but those were classified. The documents that I obtained are public, even if they were not accessible. Sooner or later they were going to bring them to the attention of the citizens. The

Pentagon Papers

were never intended to be top secret."

That material was leaked, insists the reporter.

"They weren't interviews either, but cables and memos, the written history of a small number of Pentagon insiders about how the United States got tangled up in Vietnam."

In both cases, he adds, the story can be reduced to the same statement: "a government that lies to its citizens to hide the reality of a military adventure."

"For a president to admit that he is losing the war is simply too much, so they get involved in lies. And when in the end they are discovered it is ten times worse, because to the sin of defeat, public opinion will add the sin of treason" .

Follow all the international information on

and

, or in

our weekly newsletter

.