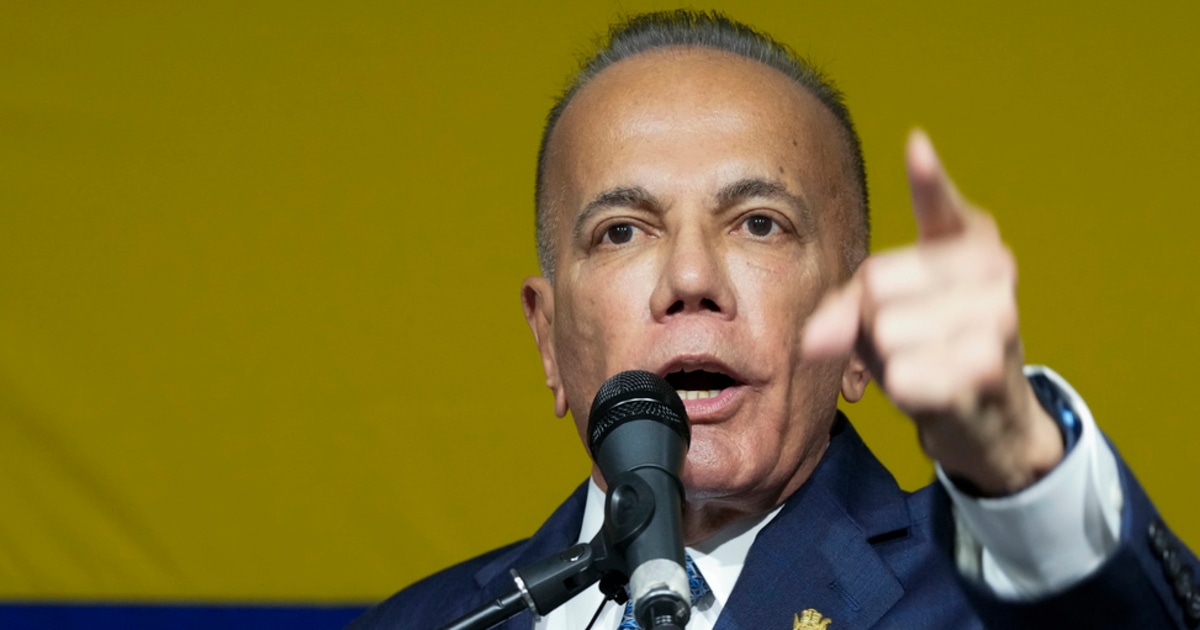

Gonzalo Sánchez, former director of the National Center for Historical Memory, at his home in Bogotá, in an image from 2019.ST

In September 2016, a few days after the signing of the peace agreement between the Colombian government and the FARC, Gonzalo Sánchez, then director of the Historical Memory Center, was optimistic.

The country was finally on the way to ending a conflict of more than five decades.

"Colombia's great challenge is knowing how to manage a country without the FARC and reorienting its policy, which has focused on fighting that armed group," he told this newspaper.

Six months after Iván Duque reaches the end of his term, Sánchez reflects on the setbacks that have prevented peace from being complete.

According to the United Nations, 303 former guerrillas, who were trying to reintegrate into civilian life, have been killed and in the regions where the guerrillas were present, the violence does not stop.

The absence of the state has given space for the National Liberation Army (ELN), the FARC dissidents and other armed groups to take control of some areas and selective displacements, massacres and assassinations are part of everyday life in Colombia, as It was before the deal.

Gonzalo Sánchez, 2016 National Peace Prize Winner, answers some questions via email to try to understand why the country has not yet got rid of the violence, which this year has already left 17 social leaders assassinated and hundreds of families looking for a place to take refuge after having been forced by violence to leave their homes.

Ask.

A few days after the signing of the peace agreement, in 2016, you said that the agreement would allow the truth about the armed conflict in Colombia to be “unearthed”.

Do you think that what has been known meets those expectations?

Answer.

I assumed that, after the signing, whatever the government was going to have continuity in the peace policies, but it was not like that.

The tasks of producing truth ran into several obstacles: a political one, the government's animosity;

another more structural, the persistence of the armed conflict in other forms, and a third, the health crisis —due to the pandemic— that imposed limits on listening in the territories of the communities and the victims.

P.

This year the report of the Truth Commission will be known, with which it is hoped to know aspects, ignored until now, about the conflict in Colombia.

Do you think it will be enough?

R.

We expect substantial contributions with that report, but there is not and will not be the total truth.

The truth is not a product but a program.

A great task remains for the new generations.

In this country there is an enormous social and institutional accumulation of truth and memory.

P.

You said that the challenge for Colombia after the agreement was to reorient its proposal for a country, which for decades was focused on the fight against the FARC, how do you evaluate the policy of the Government of Iván Duque in that regard?

R.

This government insisted on giving life on loan to the dissidents of the extinct FARC.

He gave more attention to these groups than to the daily demonstrations of peace by the bulk of the ex-guerrilla and the signatories of the agreement, who today shelter under the name of Los Comunes.

Of course, the enormous delay in changing the name [from FARC to Los Comunes] did not help either.

The ambiguity lent itself to calculated abuse.

The crimes of the dissidents are wrongly attributed to the reincorporated who are serving.

This Government insisted on war policies for a time of peace.

This made the country remain a prisoner of the discourses and dynamics of a war.

Q.

Has the way of dealing with violence changed in any way?

R.

The peace agreements were supposed to accelerate the transition towards a new vision of citizen security, democratic and guarantor of rights, such as that of mobilization and legitimate protest.

That transit was already underway with the Army sector committed to the agreement, which had understood the new times, but Duque decided to give wings to the sector that continues to see dissatisfied citizens as subversive.

Duque had everything to unite the country, but he delivers it deeply divided.

Q.

Have the extinct FARC fulfilled their part in the peace process?

R.

They have many issues pending in matters of justice and truth, but it is relevant to point out that despite the fact that an ex-combatant is assassinated almost daily, they remain convinced that the path is peace.

There is a selective myopia in demanding responsibility from the two main parties to the war: the insurgency and the State.

Q.

The FARC dissidents seem to have become a new actor in the conflict.

R.

The factions that dismembered the original trunk of the FARC [the dissidents] no longer have a political north and are entangled in the fights of the mafias.

Let's say it bluntly, the war that persists is a war without society.

P.

What is the most worrying thing about the fact that there are points of the agreement that are still not being fulfilled as expected?

A.

The patience of Saint Job is not eternal.

A collapse of the agreements, accompanied by the prolonged annihilation of the signatories, leaves the benefits of peace without reason.

The first guarantee that the signatories ask their state counterpart is the guarantee of life.

Q.

How do you rate the government's country proposal that is about to end?

R.

Duque and the government party imposed a negative program on Colombia, which is summed up in dismantling internal peace, and inciting conflict at the borders.

Gendarme of democracy in the neighborhood and despot in the criminalizing response to social protest, with dozens of deaths, injuries and torture, as everyone could see on television cameras and cell phones of protesters, bystanders and unsuspecting observers.

P.

What should be the commitment of whoever reaches the presidency in the next elections?

R.

As a society we should demand from the new president that his minimum programmatic commitment is to comply with the 1991 Constitution and with what was agreed in Havana and ratified at the Teatro Colón in Bogotá.

The program is there, you have to choose the one who has the capacity and will to carry it out.

P.

The second edition of your book

Paths of war, utopias of peace

has just come out .

Is peace the great utopia of Colombia?

R.

Before peace, democracy.

What is in crisis in Colombia is democracy.

The figures that present us as one of the most unequal societies in the world, or the largest number of displaced people or the largest number of environmentalists killed, are becoming routine for us.

And to this are added the exclusions and marginalities generated or accentuated by the pandemic, in addition to the aberrations of systemic corruption that permeates all social intermediation mechanisms, including electoral decision-making mechanisms.

Colombia has to shake its critical conscience and break with the inertia of the hopelessly bad student.

Cover of the recent book by Gonzalo Sánchez.

Subscribe here

to the EL PAÍS América

newsletter

and receive all the key information on current affairs in the region.

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/UMBJ4C443RCVDFXUVBOQGCG33I.jpg)

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/62WTZ2YGTKOGTJ6OXJW67JCCME.jpg)