The two-tier society is growing in China - Xi relies on "common prosperity"

Created: 02/13/2022, 09:58

From: China.Table

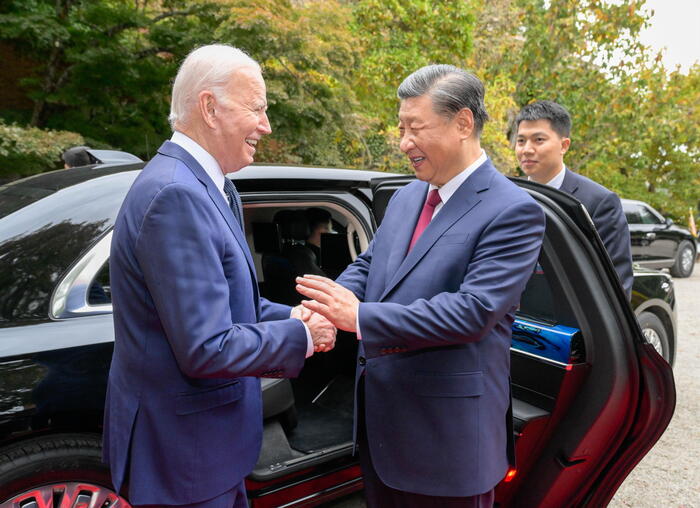

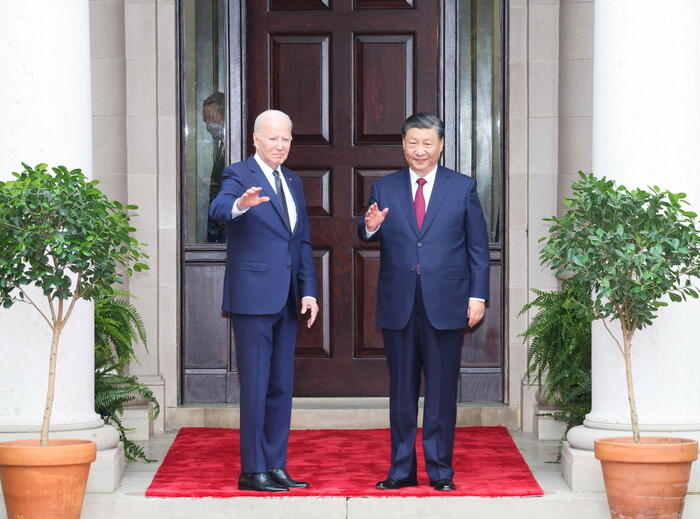

Xi Jinping recently at the Chinese New Year government reception: "Shared Prosperity" is intended to prevent social division.

© Li Tao/Imago/Xinhua

Inequality is increasing in China.

Some wallow in luxury while millions of migrant workers struggle through on meager wages.

Xi Jinping therefore launched a "Shared Prosperity" campaign.

Xi Jinping takes aim at growing inequality before extending his term as head of state and party leader again.

Wage work no longer ensures social advancement in China.

In view of rising costs, wages are too low for this.

Experts expect rather cautious measures in the campaign for "Shared Prosperity".

This article is

available to IPPEN.MEDIA

as part of a cooperation with the

China.Table Professional Briefing -

China.Table

first published it

on February 9, 2022.

Beijing/Berlin – "Common Prosperity", the goal of "common prosperity" throughout China, will remain one of the top issues on Beijing's political agenda in the year of the tiger.

At the end of 2022, Head of State Xi Jinping wants to be confirmed for another five years at the head of the Communist Party* - and thus also at the head of the state.

Everything indicates that Xi will make a big deal of the fight against inequality beforehand - at least verbally - in order to present himself as a man of the common people.

Xi Jinping has attached great importance to the goal of "Shared Prosperity".

In speeches he warned of an impending “polarization of society” and an “unbridgeable gap” caused by increasing inequality.

So far, only a few concrete details are known about how the leadership intends to create this "common prosperity".

What are the causes of inequality in China?

And can they be used to tell what the government is up to?

China: Many causes of growing inequality

Inequality in China* has many facets.

While some drive through the big cities in luxury cars, others have to fight their way through the heavy traffic as poorly paid delivery men.

While a small upper class accumulates Rolex watches and Gucci bags, poverty and a lack of prospects often still prevail in rural areas.

Millions of children of migrant workers are separated from their parents and have little opportunity for advancement.

The increasing inequality is also reflected in the figures.

In the early 1990s, the richest 10 percent of Chinese held a good 40 to 50 percent of all wealth.

In 2019, however, it was already 70 percent.

According to official figures, the Gini coefficient for income is 0.47.

Even values of 0.4 are considered a warning sign of high inequality.

(At the theoretical peak of 1, all wealth in a country belongs to one person. At zero, wealth is evenly distributed; ed.)

The causes of inequality in China are manifold.

"Right from the start, China's reform policy was aimed at getting a small group of people richer first," says economist Wan-Hsin Liu from the Kiel Institute for the World Economy (IfW).

They should boost growth and create jobs and hence prosperity for millions.

But while China's rise is unprecedented, wealth has been unequally distributed.

China: Wage labor does not make anyone rich

China's low wages contribute to this inequality.

Wages have risen in recent years.

But when it comes to the distribution of gross domestic product*, workers in China still do poorly.

Compared to companies or the state, they only receive a small part of the economic output in the form of wages or transfer payments.

While wages accounted for more than 51 percent of GDP in the mid-1990s, it has since fallen to around 40 percent – and lower than in other emerging countries.

China is in a bind here.

Because the low wages contribute significantly to the export strength of the country.

"China's export competitiveness depends on workers being allocated a relatively small share of their output, whether through wages or social transfers," writes Michael Pettis, finance professor at Peking University.

The situation is very different at the upper end of the income scale.

Politically well-connected citizens have benefited from their connections for years, says Sebastian Heilmann, professor of politics and economics in China at the University of Trier.

According to Heilmann, well-connected people have often been able to build up large fortunes through the privatization of public property, such as company shares and real estate.

China: The hukou system cements a lack of equal opportunities

The household registration (hukou) system is another classic cause of inequality.

It relegates over 200 million migrant workers to second-class citizens.

They are largely excluded from city benefits such as health insurance, the pension system, and access to public schools.

When it comes to pensions, the difference in income is particularly pronounced.

On average, people with residential registration in cities receive an annual pension of the equivalent of 5,580 euros.

Migrant workers and residents of rural regions, on the other hand, only receive an average pension of just under 280 euros per year.

The hukou system perpetuates inequality because it makes access to quality education more difficult.

Migrant workers are often unable to send their children to public city schools.

They have to resort to expensive private schools, which are often inferior to the public ones.

And if the migrant workers leave their children in the villages, the educational opportunities are even worse because the rural education system lags far behind.

Over 70 percent of urban students are admitted to college, compared to less than 5 percent of rural students, advisory agency Trivium China recently calculated.

Millions of children have lost their chances of advancement.

China: The tax and social system hardly reduces inequality

Countries around the world use the tax and social security system to at least reduce inequality somewhat.

In China, these distribution mechanisms "have hardly counteracted the ever-increasing income disparities," says Wan-Hsin Liu.

In China, the bottom 50 percent of income earners pay more in taxes than the top 50 percent,

The Wire China

reports.

Because indirect taxes such as value added tax or consumption taxes dominate the tax system.

They hit low earners particularly hard because they have to spend a larger part of their income on consumption.

In contrast, direct taxes on (high) wages and income, capital gains or real estate are low in China – or are not levied at all.

As a result, the tax system is indirectly one of the causes of inequality.

“Workers with a monthly salary of a few thousand yuan have to pay income tax.

But those who own multi-million yuan real estate assets don't need to do that," Yi Xianrong, a former researcher at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, told the South

China Morning Post

.

China's welfare system also does little to reduce inequality.

Less than 10 percent of jobseekers receive contributions from China's unemployment insurance.

And the People's Republic spends only two percent of its economic output on the country's health system - compared to around eight percent in developed countries.

"State redistribution in China has hardly any effect on the Gini index," says Bin Yan, a consultant at the consulting firm Sinolytics.

"For comparison: In Germany, state redistribution reduces the Gini index by 0.19."

China: Experts expect only cautious redistribution measures

In order to overcome "inequality, China needs far-reaching and long-term measures," says Wan-Hsin Liu.

However, observers are relatively unanimous that initially there will only be cautious reforms.

The Kiel expert assumes that there will be gradual changes in the tax system.

Because "they are comparatively simpler than reforms of the hukou system or the social and educational system".

An inheritance and real estate tax is already being discussed.

Sinolytics' Bin Yan believes the cautious introduction of a real estate tax and a capital gains tax are likely.

He also considers an expansion of social services to be likely, for example in the areas of public education and affordable housing.

Campaigns to combat all forms of illicit income may be intensified in the future, Yan said.

Doris Fischer, Professor of China Business and Economics at the University of Würzburg, is skeptical about tax reforms.

Instead, Beijing emphasizes redistribution through philanthropy.

“But charity leaves it up to companies to decide where to help.

That has little to do with fundamental reforms,” says Fischer.

She conjectures that no welfare state will be built beyond the guarantees of meeting basic needs.

In any case, this cannot be read from the previous documents on “Common Prosperity”.

So it will be more about food and a roof over your head than a decent standard of living for people on welfare.

Redistribution from businesses to households likely

Pettis, on the other hand, assumes that Beijing will not raise the minimum wage because this would make Chinese exports less competitive.

However, he also considers tax increases to be realistic.

Businesses would have to be prepared for Beijing to pass on what it sees as excess corporate and wealthy profits to middle- and working-class Chinese households in the form of tax transfers and donations.

Beijing is planning reforms for the hukou household registration system.

But they are a "risky topic" that "could trigger large population movements," says Heilmann.

For a real redistribution, "measures are required that systematically curtail the access privileges of the clientele close to the state and parties".

That too is a “risky process” for the CP.

If Xi Jinping* wants to get serious about the redistribution, "he will encounter stubborn, initially silent resistance in the ranks of the political and economic elites".

This resistance could even endanger his position and contribute to a “domestic political destabilization of China”, according to Heilmann.

Overall, Beijing has realized that "achieving shared prosperity is a long-term goal," says Liu.

In their opinion, China will proceed cautiously.

In the long term, however, China will carry out "reforms of varying intensity in many social, economic, institutional and political areas".

By Nico Beckert

Nico Beckert

has been the editor for the Table.Media Professional Briefings since January 2021.

His main topics are German-Chinese relations, economy and finance, the New Silk Road and Chinese climate policy.

Previously, Beckert wrote as a freelance author for the Tagesspiegel and the Freitag.

This article appeared on February 9, 2022 in the

China.Table Professional Briefing

newsletter - as part of a cooperation, it is now also available to the readers of the IPPEN.MEDIA portals.

*Merkur.de is an offer from

IPPEN.MEDIA

.