Retirees protest in Caracas for a decent pension, this week. Ariana Cubillos (AP)

Hyperinflation has come to an end in Venezuela.

The country has seen one of the most uncontrolled and aggressive price storms in modern history.

The trend is reversing due to the dollarization of the economy and the opening to the market.

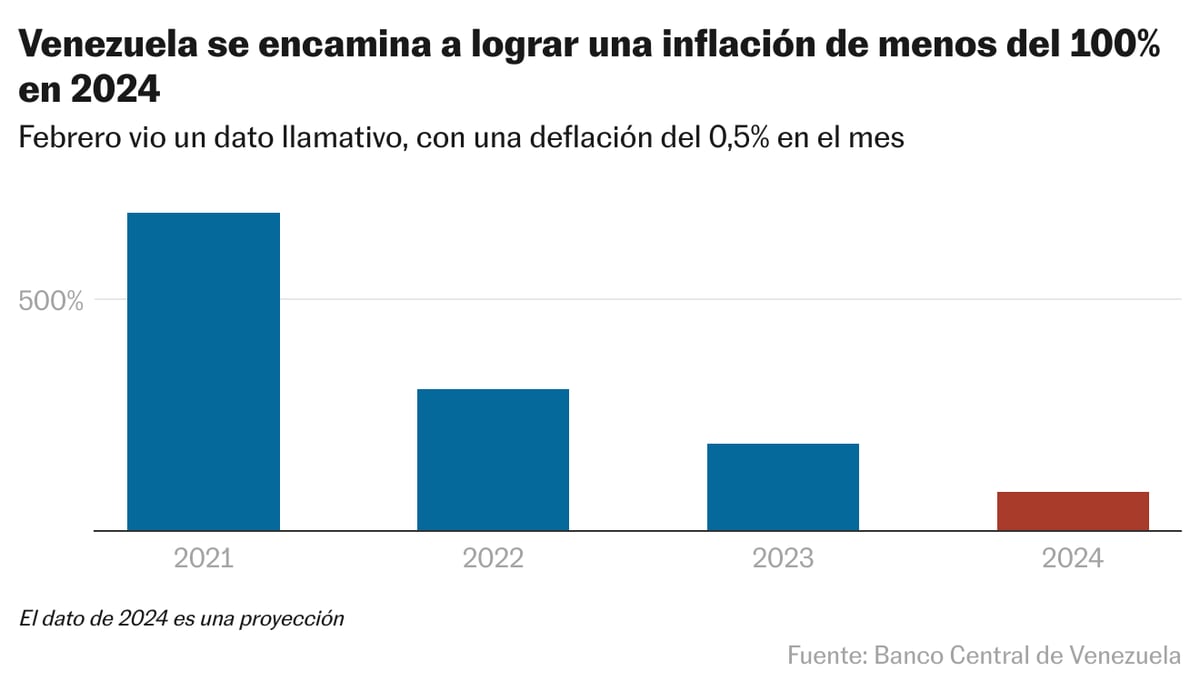

The inflation rate in Venezuela last February was 2.9%, the lowest average registered in the local economy in several years, and the behavior of prices will be around 36% in 2022. This is the fourth consecutive month in which the increase in prices registers single-digit averages.

The decrease has materialized from one month to another.

In the last 12 months, the consumer price index has been below 50% month-on-month.

And since September, below 10. The price of the dollar has been stabilized for several months around 4.5 bolívares, after the third advanced monetary reconversion in Venezuela in just over ten years.

Last year, the Consumer Price Index reached 686%.

In 2020, it was 2,900%.

In 2019, 7,300%.

The end of hyperinflation in Venezuela seems ready to consolidate.

The ravages of the economic storm that has been taking flight since 2013, when Nicolás Maduro assumed the presidency of the Republic, and that erupted with fury in 2017. Its consequences have been devastating in the social and economic field.

With the catastrophe consummated, salaries pulverized, the productive apparatus destroyed, employment burned, the volume of the diaspora consolidated, many people wonder how the Maduro government has managed to stop this devilish trend, to which it rarely refers in public.

Maduro has decided to stop doing what he had been doing for years: "The government has finally renounced financing the deficit of public companies through the issuance of money without backing," says economist Víctor Alvarez, a former minister of industry.

“There has been an adjustment of rates of state companies and services that are increased surreptitiously and gradually;

the level of public spending has been reduced for the first time in all these years.

The Government has advanced a commercial policy of opening the internal market, allowing all kinds of imports without tariffs and without paying VAT.

That lowers costs.

There is a new exchange policy, the control strategy has been abandoned.

A high legal reserve has been placed to dry up banking liquidity.”

For most of the 20th century, Venezuela enjoyed single-digit annualized inflation.

This trend began to crack in the late 1980s, when it climbed to averages of 30 and 35% per year.

With all the upheavals that came later, the feeling seemed consolidated that oil income protected the national economy from a phenomenon that became common in Latin America, but that Venezuela had never experienced.

Without announcing it, the Maduro government has decided to change the rules of the game of chavismo in these years, tending to excessively regulate the economy, control the business community and problematize private property.

The collectivist and state productive projects of Chávez and Maduro failed completely.

Henkel García, financial analyst and managing partner of the Econometric firm, maintains that the uncontrolled growth of prices experienced by the country finds one of its reasons "in the collapse of national production", in crisis after the wave of expropriations carried out by Hugo Chavez.

In addition, he affirms, in the development of a mistaken monetary and fiscal policy, determined to force price increases divorced from the economic context and to regulate the profit margin of companies.

“In 2018, Maduro decides to increase the salary by an astronomical figure, inconceivable, close to 18,000%.

To pay for this increase, inorganic money had to be issued.

The monetary issue of that time was immense.

The Government financed the payroll of the state companies, all bankrupt.

The Central Bank had no autonomy.

The Venezuelan lost all confidence in the Bolivar.

In the economic and business sector there was a lot of nervousness.

That was opening the floodgates of dollarization.”

For several months, Ecuadorian technicians close to Rafael Correa have been advising the Vice Presidency of the Republic to design a new economic strategy, much more similar to the one proposed by critics of Chavismo than to the one based on Chavista postulates.

The 37 months that the Venezuelan hyperinflation comprised have come to an end, as Francisco Rodríguez, an academic and managing partner of the firm Torino Capital, points out, as a consequence of a process that has some inertia.

“There is no hyperinflation that lasts 10 years.

The average duration of processes like these is 20 months.

It is not a successful experience that Maduro advances.

It is an adjustment that has been delayed.”

"Hyperinflation consumes itself like fires, there comes a time when there is nothing left to burn," Rodríguez continues.

“What Maduro did is finance his operations by taking away the value of the money that people have in their hands.

Hyperinflation forces you in the end to make the adjustment you didn't want to make.

It materializes through the deterioration of the real wage of the public worker.

Public spending is now lower because what you are paying is very little.”

Subscribe here to the EL PAÍS América

newsletter

and receive all the key information on current affairs in the region