The curator and fashion critic Andrew Bolton (Lancashire, United Kingdom, 55 years old) assures that, if he brought together all the designs by John Galliano that he has included for decades in his exhibitions at the Metropolitan Museum of New York, the total number of pieces would give to organize an individual retrospective of the Gibraltarian.

"He's one of my favorite designers," he explains.

“Fashion doesn't always come off with flying colors when it enters museums because the status of garments changes when they are exposed to the public.

On a mannequin, garments lack dynamism because fashion is designed to be worn on the body, in motion.

But, on the other hand, exhibiting them allows the public to get closer to them and appreciate their construction, their embroidery, their details, which are fundamental in an art museum.

John's clothes pass with flying colours.

exposed,

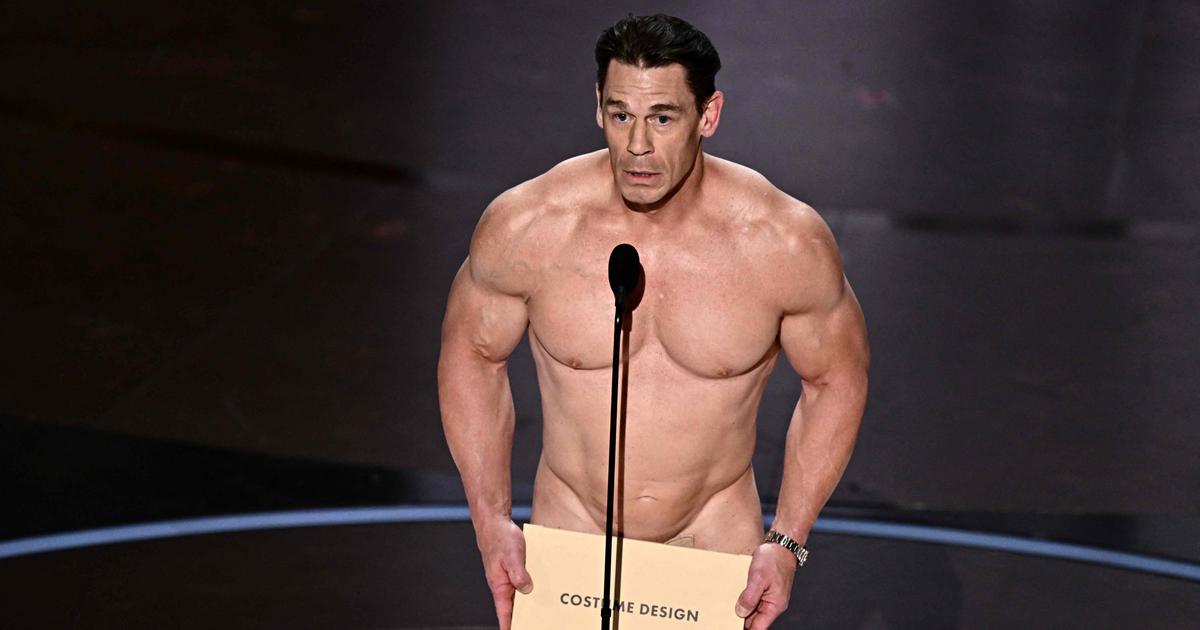

At the moment, the temple of New York fashion does not plan to dedicate any monographic exhibition to Galliano, but Bolton has served as curator in an equally ambitious project:

Dior by John Galliano

, the book that the Assouline publishing house dedicates to the stage of the Englishman in the artistic direction of Christian Dior, the luxury firm where he achieved stratospheric fame for almost 15 years, from 1997 to 2011, and from which he left abruptly in an episode that it marked the descent into hell of the most excessive designer of the turn of the century.

"The approach of the book is purely chronological," Bolton explains in a videoconference interview from Paris.

"This volume comes after those dedicated to Christian Dior, Yves Saint Laurent, March Bohan and Gianfranco Ferré," he says, referring to the creative directors of the house from 1947, the date of its foundation, until the arrival of Galliano.

"The book begins with the dress he designed for Diana of Wales for Dior's 50th anniversary Met Gala and runs through his latest collection."

Jumpsuit belonging to the spring-summer 2000 haute couture collection. Laziz Hamani

The approach of the volume is Cartesian, but under the index beats one of the most volcanic legacies of contemporary fashion.

The book brings together historical photographs and new details of garments belonging mainly to the haute couture lines that Galliano revived at a time when these departments, once the jewel in the crown of Parisian houses that could afford them, languished as obsolete witnesses of other time.

At that time, in the mid-nineties, the house was already owned by the luxury giant LVMH and a milestone in French fashion with its own chapter in the history books.

The origin of the myth dates back to 1947. Shortly after the end of World War II, Christian Dior's first collection marked the recovery of haute couture after the war and underpinned a new way of understanding design.

In a few years marked by the austerity of a traumatic post-war period, Dior knew how to change the center of gravity of the sector.

Instead of substituting one exotic inspiration for another, the cyclical renewal of fashion would come from the construction technique of the garments.

He himself, Dior, assumed the creation each season of a different silhouette,

recognizable at first sight and easily identifiable in the black and white photographs of fashion magazines.

His impact was decisive, he opened the door to the golden years of haute couture —master craftsmen of the stature of Balenciaga or Givenchy were needed to keep up with him—and, despite his short career —Dior died in 1957, barely a decade after its triumphant premiere—, it was able to generate an imaginary and a repertoire that, in one way or another, continues to articulate the brand today.

Galliano, who took over from Gianfranco Ferré, was not French, he had been educated in London subcultures and brought together two apparently incompatible worlds.

On the one hand, he had experience as a tailor and as a dressmaker, which allowed him to raise the technical complexity of his designs.

On the other hand, an extravagant and overflowing imagination that he pushed to the limit making opposing concepts collide like moving trains.

Masai and

belle époque

;

Egypt and the fifties;

bar jackets —the emblem of the house—, Mata Hari and Indian princesses from the Victorian era;

the Ballets Russes and the Marquise Casati;

Pocahontas and Elizabethan pomp;

The portrait of Dorian Gray

and the tabloid press;

China, Japan,

pin ups

, Hollywood divas and batas de cola.

Striking effects, after all, that aroused the same adrenaline as Dior's silhouettes half a century ago.

Every season, a surprise.

Nothing was alien to the omnivorous desire of that designer who, in those boom years, created garments made by hand for weeks by artisans full of skill and patience, without budget limits.

“John is a consummate postmodernist, so he worked from historicism, eclecticism, and deconstruction.

He was at times provocative and at times directly controversial, but it was extraordinary, because he knew how to align the spirit of Dior, that of the

Zeitgeist

and his own,” says Bolton.

"Those seemingly incongruous provocations helped evolve Christian Dior's stylistic lexicon."

Spring-summer 2004 haute couture gold sequin suit. Laziz Hamani

Design belonging to haute couture fall-winter 2008. Laziz Hamani

The researcher affirms that during the process of documenting the book he has come across an accomplished narrator.

“Galliano was able to synthesize history, other cultures, film, pop culture and fashion into a compelling and very contemporary

collage

of his own,” he explains.

“Before starting this book I already knew that John was a very good researcher, but not to what extent.

Until 2001 he consulted books and went to museums, but on that date he began to schedule very extensive trips, three or four weeks, to document himself.

He would go to China, Russia, Japan or Egypt, and then he would synthesize everything in the collection”.

Bolton cites examples such as his first spring-summer 1997 couture collection titled

Maasai Mitzah

.

“He established a link between the Dinka corsets of the Maasai culture and the

belle époque

silhouette, ” he explains.

“And he did it through the corset, expanding the beaded necklace to the abdomen and giving it a curvature typical of the silhouette of the early twentieth century.

It is something very thoughtful, very complex.

It reveals a very sophisticated look.”

Or, in 2007, an explosive dialogue between the H silhouette devised by Dior in the fifties and an Egyptian imaginary halfway between archaeology, hip hop and Hollywood biblical cinema.

"It's fascinating how he translated Dior's hip-flattening H line through the visual codes of Ancient Egypt."

Following his abrupt departure from Dior over anti-Semitic remarks, Galliano embarked on a notorious via crucis—repentance, rehabilitation process, public apology—that concluded in 2014 with his appointment as artistic director of Maison Margiela, the conceptual fashion house of Belgian origin. which today is owned by the group Only The Brave, and where Galliano has taken his extremely free aesthetic to new heights.

Bolton assures that Galliano proudly remembers his achievements at Dior.

“When I was preparing the book, I spoke with him privately, to check some facts,” he explains.

“He saw the final design and was very excited to see all of his work in a book.

I think he is very proud of what he did at Dior during those 15 years.

It was something very from his time,

that it could not happen now and that it will not happen again because it is important that fashion reflects the changes of each moment.

But it is an example of freedom of thought.”

Spring-summer 1997 haute couture outfit. Laziz Hamani

Bolton assures that the years that have elapsed since the period documented in the book impose a change of approach.

“Galiano's designs hold their own as works of art and haute couture, as magnificent displays of creativity and imagination, and as examples of sublime craftsmanship.

But today's world is very different from the late 1990s.

Today's designers do not have the privilege of that freedom of thought.

When John introduced

Maasai Mitzah

there was not a single mention of cultural appropriation.

Today that collection would be impossible because fashion has aligned itself with current politics, and it is good that it is so, but I think they are still valid as works of art”.

It is at this point that professionals in the history of fashion come into play, among whom Bolton - chief curator of the Met's Costume Institute and responsible for monumental fashion retrospectives dedicated to Alexander McQueen, Rei Kawakubo or Charles James - enjoys a undeniable prestige.

From that position, he outlines what new designers can learn from those almost legendary years.

“Galliano's highly complex creativity, his untethered imagination, his depth, his freedom of thought and his ability to provoke continue to be admirable,” he says.

“John tested the pragmatics of fashion.

People said that their clothes were very beautiful, but then they asked: how do they wear them? Who wears them?

The pragmatics of fashion is one thing, but fashion also has the power to transform things and make us think differently.

That talent for imagining other worlds is the key to John's legacy."

Exclusive content for subscribers

read without limits

subscribe

I'm already a subscriber