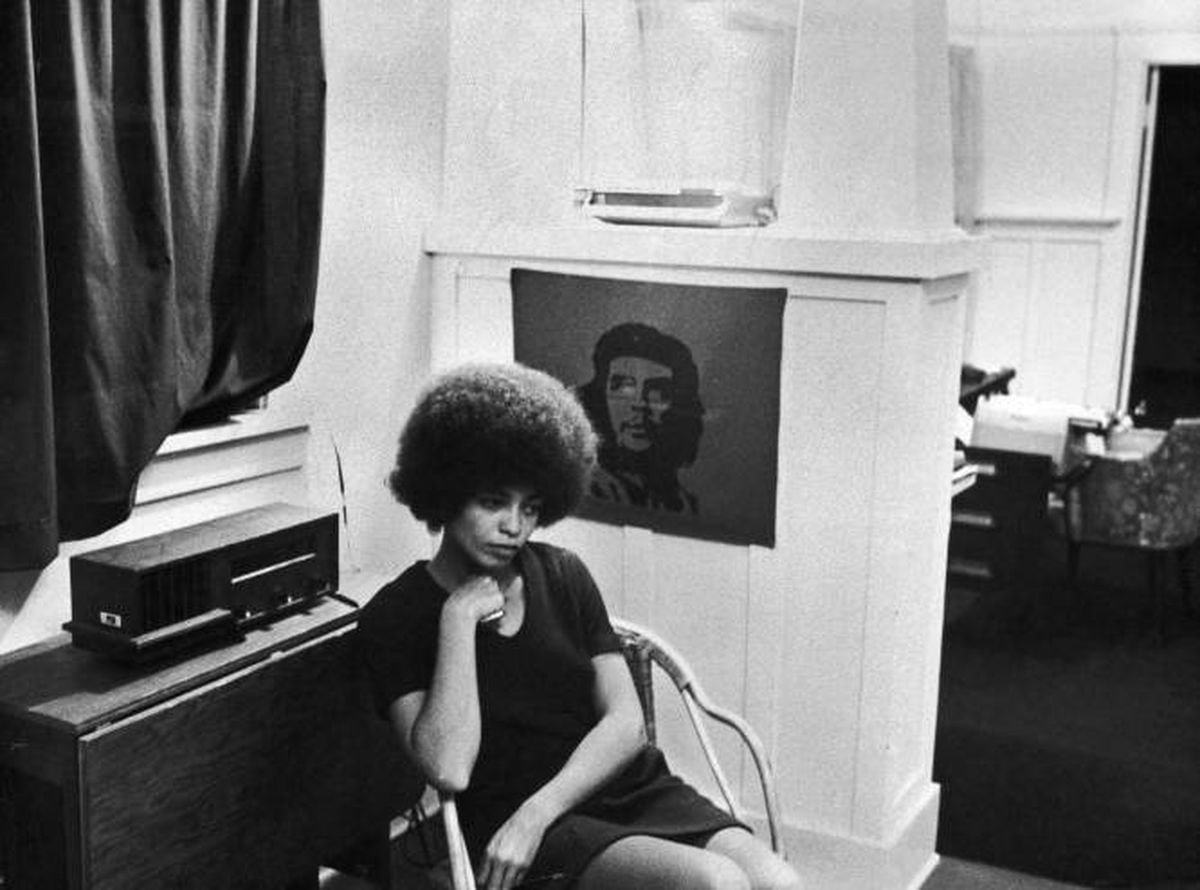

Liliana Rondón, Nancy Morales, María Roa and Nieves Fontecha, four Colombian women who support Francia MárquezCourtesy

“I represent the nobodies and nobodies of Colombia,” said Francia Márquez, vice-presidential candidate for the Historical Pact, in all her public addresses since she began the race for power alongside Gustavo Petro.

Her words refer to the poem by the Uruguayan writer Eduardo Galeano:

The Nobody: Nobody's children, the owners of nothing.

The nobodies: the nobodies, the nobodies, the hare running, life dying, screwed up, screwed up (...)

Her slogan has become an essential part of the campaign and resonates strongly with many poor and working women who for the first time feel identified with a national political project.

Peasant women, domestic workers, informal vendors, indigenous people and recyclers explain the reasons for their support of Francia Márquez.

None of the interviewees is part of the campaign.

Nieves Fontecha, 64 years old, peasant from Vélez, Santander

Nieves Fontecha gets up every day at five in the morning.

She listens to the news, makes dark coffee and milks her three cows before the sun has risen.

She feeds the chickens and pigs, checks the guava crop, and goes home for breakfast.

Nieves lives on a small farm in the village of El Gualilo, two hours from Vélez, in Santander, and like millions of peasants in Colombia, she has to make many efforts to survive.

According to the latest official figures, in the country there are more than seven million peasants who live in poverty and more than two and a half million who live in extreme poverty, with less than 1.9 dollars a day.

“Governments do not listen to the voice of farmers.

The roads are in very bad condition.

It is very difficult to take out and sell our products.

Our crops are damaged,” says Nieves by phone.

“In the field people suffer a lot.

We work at a loss.

We need a change".

For her, Francia Márquez is that change: “France represents me: as a woman, as head of a family, as the voice of ordinary people, of poor people.”

“The agricultural sector is one of the most abandoned by the State.

We do not have enough support, subsidies, or access to credit.

We are part of the nobodies."

Mrs. Nieves insists that it is the first time in a long time that she and the peasants in her village have real hope in politics.

"I ask France to please not disappoint us, not to forget us when it comes to power."

Persides María Roa and Claribed Palacios, domestic workers from Medellín

Persides Roa and Claribel Palacios are part of the Union of Afro-Colombian Domestic Service Workers.

Both are victims of violence.

The two have worked for many years as employees in the homes of wealthy families in Medellín.

And, now, the two lead a fight to improve the labor rights of the more than 500,000 domestic workers that there were in 2021 in Colombia, according to DANE figures.

“Francia is a very capable woman, very intelligent, a brat, but unfortunately in this country when you are black they think you can only cook or sweep,” says Claribed with indignation, recalling that recently several people wrote on social networks that Francia Márquez I was going to be Gustavo Petro's cook.

Persides Roa recognizes that she and her companions are part of the nobodies to which Márquez refers.

“We have always been invisible, we have been in the shadows, we clean the houses of others, but we do not have our own house.”

"With France, domestic workers are also going to be able to live tasty."

Persides and Claribed agree that if a black and poor woman reaches the vice presidency it would be a very important symbolic and political advance for Colombia.

His words recall the statements that Francia Márquez gave in his last press conference to defend himself against the accusations without evidence made by the senator of the Conservative party Juan Diego Gómez of having links with the ELN guerrilla: "What bothers the president of the Senate is that today a woman who could be the employee of the service of her house is going to be her next vice president.

Liliana Rondón, 48 years old, informal vendor from Bogotá

Liliana Rondón is 43 years old, she is an informal vendor and works every day so that her two children do not lack for anything.

“I started at a very young age selling pizzas on the street.

I have sold flowers, makeup, pajamas, kitchen cleaners”, she tells by phone.

Liliana lives in Bosa, an impoverished town in the south of Bogotá.

“Street vendors work all day on the street.

We endure the rain, the cold, the heat, the persecution of the police, the bad face of the owner of the premises, the rudeness of the pedestrian.

At the end of the day we managed to take home 30,000 pesos, less than 10 dollars”.

Just like Liliana, the 40,000 street vendors in Bogotá don't contribute to a pension, they don't have social security, or health insurance, or occupational hazards.

“Sometimes we get sick, but we can't stop working.

If we stop for a day, our families don't eat.

It can't go on like this.

We need decent living conditions.”

Liliana explains that she is going to vote for Francia Márquez because she is a woman who knows what it is like not to have money for breakfast.

"When a person knows poverty, he understands the problems of society."

And she confesses that she feels identified with the idea of nobodies.

“Informal vendors are at zero.

We have never had political representation.

We have no one to stand up for us, no one to assert our rights.”

Nancy Morales Tombé, 37 years old, indigenous Misak from Silvia, Cauca

"My dad didn't want his daughters to be submissive, he wanted us to go to college."

This is how the story of Nancy Morales Tombé begins, a Misak indigenous woman who was born in Silvia, Cauca, but years ago she had to leave her territory due to violence.

Nancy now lives in Bogotá, works in the public sector, but she remembers how she and her sisters didn't even have money to take a bus to study in the city: “The Misak are an impoverished people.

The basis of our economy is agriculture.

We plant onions, garlic, potatoes, things that the earth gives in cold weather.”

Nancy says that sometimes she goes around the city dressed in the dress of her people and people approach her and ask if she is from Peru, Ecuador or Bolivia.

“They don't think I'm from here, from Colombia.

They see me as a stranger, as a foreigner.

That is why I feel part of the nobodies, of those who are not recognized or listened to.”

Today in Colombia there are 680,000 indigenous women like Nancy who belong to 115 different ethnic communities.

In her first jobs in the city, Nancy remembers that her colleagues looked at her strangely, from head to toe.

"I felt that they judged me, that they thought she was less intelligent, that she did not deserve to be there."

The social and racial discrimination that she has suffered is still suffered today by thousands of indigenous men and women who see an opportunity in Francia Márquez's project.

“Finally, after so many years of neglect, there is an illusion of ethnic representativeness in the head of a woman who has also experienced racism.

Hopefully that will serve for Colombia to remember that we also exist”.

Jenny Camelo, 33 years old, waste picker from Bogotá

Jenny Camelo leaves for work earlier than Mrs. Nieves.

She wakes up at four in the morning, takes her cart and goes to walk the streets of Ciudad Bolívar, south of Bogotá, looking for garbage to recycle.

Her first route can last three or four hours.

"I collect paper, cardboard, plastic bags, tubes, scrap."

She separates the materials, sorts them and takes them to a warehouse to sell them.

At the end of the day, Jenny, who is part of the Friends of the Earth Trade Recyclers Association, gets 10,000 or 15,000 pesos, more or less three dollars.

That is enough for him to eat and pay for the services of his home.

For her and her colleagues, more than 25,000 in Bogotá alone, eating three times a day is a luxury that is difficult to fulfill.

His support for the political project of Francia Márquez can be summed up in a simple phrase: “The poor have to help the poor”.

Jenny explains that it is time to give another person, who is not part of the Colombian political elite, the opportunity to represent them.

“The candidates only remember us when there are elections, they promise us that they are going to help us improve our living conditions and then they disappear.

We hope that the same does not happen with France”.

Subscribe here to the EL PAÍS América newsletter and receive all the current regulatory keys in the region.

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/L6TCOQ5HGZCWTOW6YNBMMGDKBA.jpg)

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/Z3C74GDWPZH2JMJB4EIL7Q7S4I.jpg)