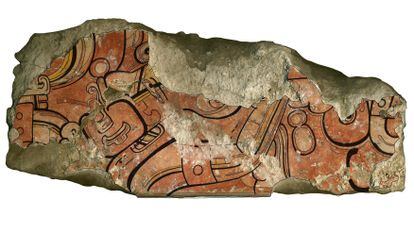

These fragments show one of the days of the Tzolkin calendar, with the dot and dash of the number seven and the head of a deer. Karl Taube.

Courtesy of the San Bartolo-Xultun Regional Archaeological Project

In 2001 a group of archaeologists led by William Saturno discovered a new semi-hidden Mayan city in the jungle of El Petén, in Guatemala.

The place known as San Bartolo stood out for its pyramid built in successive phases, one on top of the other.

They called it

Las Pinturas

, thus in Spanish, after one of the treasures they found in the first chamber: murals painted in bright colors reminiscent of the frescoes of Roman Pompeii.

Between illustrations of their gods and the origin of the world, there was one of the first samples of the writing of the Mesoamerican civilization.

Now, the first reference to the Mayan calendar has been identified in two mural fragments found deep within

Las Pinturas.

.

The finding shows that the Mayans organized time in a ritual way much earlier than previously believed.

Boris Beltrán was a student at the University of San Carlos in Guatemala City when he joined the San Bartolo excavation team in 2004. Today he is co-director of the San Bartolo-Xultun Regional Archaeological Project and remembers how, four years later, he found the first reference to the Mayan calendar: "When we found the fragments in the center of the pyramid, we did not realize what it was, but he kept repeating, they are paintings, they are paintings."

His colleague Heather Hurst, an archaeologist at Skidmore College (United States) and co-director of the site, repeated that “it can't be, it can't be”.

But it was.

There they found more than 7,000 fragments of murals painted on the stucco of the walls.

Using radiocarbon dating of charred wood remains from the fill,

"When we found the fragments in the center of the pyramid, we didn't realize what it was, but he kept repeating, they are paintings, they are paintings."

Boris Beltrán is co-director of the San Bartolo-Xultun Regional Archaeological Project

“It was the Mayans themselves who knocked down the wall to enlarge the pyramid.

But the care with which they dismantled the mural, how they removed the plaster, how they deposited it inside the chamber... As if it were a constructive rule of the Mayans.

When a new structure is made, they bury the old one.

It doesn't just break and is thrown away, it's something sacred, as if they were burying the family,” says Beltrán.

“When painting an image, the Mayans believed that the act of painting brought the figure to life.

So when the end of its use came, they had to remove it with respect, "adds Hurst.

For more than 10 years, Hurst, Beltrán and other archaeologists, including David Stuart, director of the Mesoamerica Center at the University of Texas at Austin, who was involved in the initial discovery, have been trying to solve this puzzle of 7,000 fragments.

With the help of sophisticated imaging technologies and their accumulated knowledge of the Mayan civilization, they have managed to recompose scenes that show the origin of the world according to the Mayans, of their gods, such as the corn god or the sun god rising from the mountain... But They have also found glyphs that give new clues about key aspects of that civilization.

One is the first written reference to the governor paired with a figure on a throne in paintings from 100 years before this era, the first evidence of a king centuries before the famous kings of Tikal,

Ceibal or Palenque.

A complex social organization and hierarchy of power already existed.

Fragment of the stucco depicting the corn god Heather Hurst

Among the thousands of fragments there are two that refer to the Tzolk'in, the sacred calendar.

The details of his discovery have just been published in the scientific journal

Science Advances

.

Classified as #4778, one of the pieces shows a dot and a horizontal line.

It is missing a piece and there, the researchers maintain, a second point should go.

The Mayans wrote the number 7 with two dots on top of a line.

Between the lower part of this first fragment and the second, the head of a deer or deer can be clearly seen.

And the seven deer is one of the days of the Tzolk'in.

Made up of 260 days that "reminiscent of the length of human gestation," says Hurst, the almanac has no months.

Instead, it is made up of 20 days represented by glyphs and numbered from 1 to 13 in a cyclical fashion.

The seven deer was followed by 8 stars, 9 jade/water, 10 dogs, 11 monkeys...

"The Mayans have a solar calendar, like us, but they also have a ritual one," says Hurst.

"We also have one, Holy Week is part of that sequence of rituals throughout the year," she adds.

It was associated with a mythology of origin and also to mark the celebrations that accompanied the Haab, the 360-day calendar.

The remaining five, although they were counted, were disastrous and people avoided leaving their homes.

Surrounding both was the calendar wheel, which completed its cycle every 52 years.

The complex way that the Mayans had to organize time is completed with the long count, a vigesimal system (base 20) of counting the days linearly.

It is with the latter that it has been possible to find equivalencies between the Mayan calendar and the Gregorian calendar.

“The Mayans have a solar calendar, like us, but they also have a ritual one.

We also have one, Holy Week is part of that sequence of rituals throughout the year”

Heather Hurst, co-director of the San Bartolo-Xultun Regional Archaeological Project

The relevance of the discovery of the seven deer lies in the fact that it would be "the oldest recorded date, in this case on a mural," according to Beltrán.

But they must have been using it for a long time.

San Bartolo already existed about 400 years ago of this era.

The very style of the scribes "so refined", as Hurst points out, suggests a tradition that came from further back.

In addition, although the Maya and other Mesoamerican peoples had different ways of organizing power and different societies, they used the same ritual calendar seen in San Bartolo, a calendar that is still used by indigenous communities.

For the discoverers of the seven deer, San Bartolo still has many secrets to reveal.

Some are still inside the pyramid.

But others are out.

Four roads lead to or leave from the city.

"San Bartolo is at the center of something, now we have our eyes on where these roads end," says archaeologist Heather Hurst.

You can follow

MATERIA

on

,

and

, or sign up here to receive

our weekly newsletter

.