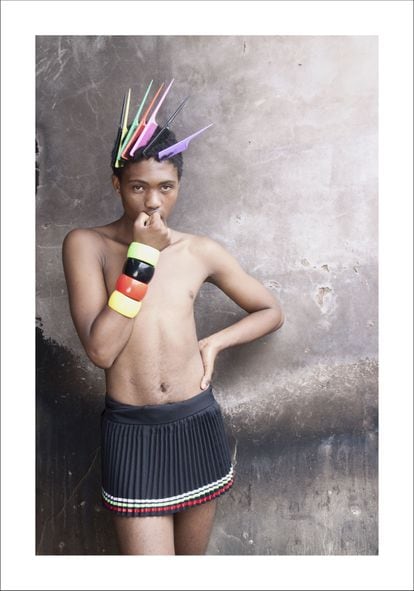

'Xiniwe at Cassilhaus' (2016), Zanele Muholi's self-portrait.

With a bar that is difficult to match right now in Spanish museums, the Valencian Institute of Modern Art (IVAM) proposes two exhibitions that not only work wonderfully well together.

They will also survive the evaporation of the impact of their themes, such as exploitation, racism and homophobia, three types of blindness that arise from the same root.

The first presents the work of Anna Boghiguian, an Armenian-born artist born in Cairo who investigates capitalism as a form of oppression that damages cultures and annihilates individuals.

Her drawings and installations, created under the vulnerable aspect of truth (so hard to find today), first flicker and then are a moving visual thunder, the distillation of her natural gift to represent historical processes that visit us again and again. again:

the traffic of goods through the Suez Canal, the Treaty of Versailles, the overexploitation of natural resources and the climate emergency, all colliding in a more or less arbitrary scenario.

The second exhibition, which could already be seen at the Tate Modern in London and at the Gropius Bau in Berlin, stars Zanele Muholi, who identifies as a non-binary person and appears body and soul as a "visual activist" through his photographic archive that documents —and, at times, biasedly stylizes— the lives of LGTBIQ+ groups.

Both works satisfy the only feeling we can be sure of today: our capacity for transformation.

In the words of Hannah Arendt: "The essence of human freedom is the creation of new things."

the overexploitation of natural resources and the climate emergency, all colliding in a more or less arbitrary scenario.

The second exhibition, which could already be seen at the Tate Modern in London and at the Gropius Bau in Berlin, stars Zanele Muholi, who identifies as a non-binary person and appears body and soul as a "visual activist" through his photographic archive that documents —and, at times, biasedly stylizes— the lives of LGTBIQ+ groups.

Both works satisfy the only feeling we can be sure of today: our capacity for transformation.

In the words of Hannah Arendt: "The essence of human freedom is the creation of new things."

the overexploitation of natural resources and the climate emergency, all colliding in a more or less arbitrary scenario.

The second exhibition, which could already be seen at the Tate Modern in London and at the Gropius Bau in Berlin, stars Zanele Muholi, who identifies as a non-binary person and appears body and soul as a "visual activist" through his photographic archive that documents —and, at times, biasedly stylizes— the lives of LGTBIQ+ groups.

Both works satisfy the only feeling we can be sure of today: our capacity for transformation.

In the words of Hannah Arendt: "The essence of human freedom is the creation of new things."

which could already be seen at the Tate Modern in London and at the Gropius Bau in Berlin, stars Zanele Muholi, who identifies as a non-binary person and appears body and soul as a "visual activist" through his photographic archive that documents —and, at times, tendentiously stylizes— the lives of LGTBIQ+ groups.

Both works satisfy the only feeling we can be sure of today: our capacity for transformation.

In the words of Hannah Arendt: "The essence of human freedom is the creation of new things."

which could already be seen at the Tate Modern in London and at the Gropius Bau in Berlin, stars Zanele Muholi, who identifies as a non-binary person and appears body and soul as a "visual activist" through his photographic archive that documents —and, at times, tendentiously stylizes— the lives of LGTBIQ+ groups.

Both works satisfy the only feeling we can be sure of today: our capacity for transformation.

In the words of Hannah Arendt: "The essence of human freedom is the creation of new things."

biasedly stylizes the lives of LGTBIQ+ groups.

Both works satisfy the only feeling we can be sure of today: our capacity for transformation.

In the words of Hannah Arendt: "The essence of human freedom is the creation of new things."

biasedly stylizes the lives of LGTBIQ+ groups.

Both works satisfy the only feeling we can be sure of today: our capacity for transformation.

In the words of Hannah Arendt: "The essence of human freedom is the creation of new things."

At this point, Muholi's photographs repudiate victimization and persuasively celebrate the erotic wisdom of any life, no matter how much we see in a

black and South African

queer archive.

The most interesting thing about this work is that it teaches us to ask ourselves an inverse but crucial question in the halls of a museum.

What does the author think of us?

Freed from the exhausting task of suffering for having been silenced, assaulted or raped, the people portrayed simply express themselves over and over again, in nature and on the streets that were denied them during the

apartheid years.

and still today, on beaches and mountains, before the fight and after the ecstasy.

They are vigorous presences whose defiant gaze disarms us: strong madonnas, beauty queens and disguised warriors surrender themselves to the fiction of their bodies, symbolically transmitting a naked truth about their own enjoyment, swaying over time, like the Orlando who fabled Virginia Woolf, the young man who, suddenly —three centuries of history—, becomes a woman.

The transformation of the body, step by step, triumphs over time.

It is a real and difficult pleasure.

Muholi's queer

aesthetic

might seem quaint, but it's just plain provocative.

'Mini Mbartha, Glebelands, Durban, 2010'.

Zanele Muholi's work at IVAM

In Spain, his photographs were exhibited for the first time at Casa Africa in 2012 and, since then, have visibly occupied the halls of biennials, such as Documenta 13 and those of Venice in 2013 and 2019. The set of 260 images and videos that now presents the IVAM is divided into five rooms, following a circular logic, from the most recent of

Somnyama Ngonyama

(in his native Zulu language, "hail, dark lioness"), an unfinished series that he undertook a decade ago with stereotyped self-portraits of the black goddesses, their bodies and heads decorated with combs and beads found in African markets.

Ends in

Faces and Phases,

still unfinished series started in 2006, a selection from his Photo XP Archive, with more than 500 photographs about the many facets of black

queer

existence , from pride, protest and migration to weddings and funerals.

Muholi images repudiate victimization and celebrate the erotic wisdom of any life

To claim that Muholi's work is universal is not inappropriate in the context in which it takes place, post-

apartheid South Africa,

the first country in the world to ban discrimination based on sexual orientation, inscribed in the 1996 Constitution. they follow the genealogy of feminist artists from more than half a century ago, since they denounce the impossibility of current societies to recognize the concept of difference in terms of human dynamic force.

We are change.

Muholi was a girl raised in full racial segregation, she worked in a factory, was a hairdresser and later an activist after verifying that not even the newly launched democracy protected women from hate crimes.

“I want to rewrite

queer history

and trans black South African so that the world knows of our existence, resistance and persistence”, he decided.

With her camera, she documented those lives with another approach, because instead of portrayed passive beings they would be “participants” in a collaborative process, friends, co-producers, comrades.

Muholi subverts stereotypes (

Manet 's

Olympia ,

Girl with a Pearl Earring,

the Statue of Liberty).

In the post-production process of her self-portraits, the effect of color increases, causing the skin to darken, an extremely meticulous skill by which the images never lose their affirmation in front of the viewer.

“I know what you think of me.

I raise the contrast, you lower your voice”, he seems to tell us.

One of the rooms of the Zanele Muholi exhibition at the IVAM, last April 5.Miguel Lorenzo

Documentary filmmaker Joan E. Biren's work is as crucial to Muholi as Lisette Model was to Diane Arbus.

She was introduced to her work during a master's degree in Toronto, especially her two self-published books,

Eye to Eye: Portraits of Lesbians

(1979) and

Making a Way: Lesbians Out Front

(1987), which evaporated the dearth of lesbian stereotypes (vampires and erotic pubescent scenes by David Hamilton) imprinting them with another character —and another destiny— within their daily lives, visible in a wide-ranging family album.

Today, like Biren (his collection of 65,000 photographs of her, which makes up the most important study of lesbian culture in the United States, is deposited at Smith College), Muholi continues to carry out an insurgent, commemorative "visual activism" with the communities

black

queer from South African

townships

or residential areas.

In our world of obscene visibility, her motto takes on all the nuances: "You can't start a libertarian movement without being seen."

'Zanele Muholi'.

IVAM.

Valencia.

Until September 4.

You can follow BABELIA on

and

, or sign up here to receive

our weekly newsletter

.

Exclusive content for subscribers

read without limits

subscribe

I'm already a subscriber