By Paula Andalo | KHN

In December 2020, the Fierro family, from Yuma, Arizona, began to have a streak of medical bad luck.

That month, Jesús Fierro Sr. was hospitalized with a serious condition of COVID-19.

He spent 18 days at Yuma Regional Medical Center, where he lost 60 pounds.

He returned home weak from him and carrying an oxygen tank so he could breathe.

Then, in June 2021, his wife, Claudia, passed out while the family was waiting for a table at the Olive Garden restaurant.

One second she felt dizzy, and the next she was in an ambulance on her way to the same health center where her husband had been.

She was told that her magnesium levels were low and she was sent home in less than 24 hours.

The family has health insurance through Jesús Sr.'s job, but

the coverage did not protect them from racking up thousands of dollars in debt.

[“People are dying for preventive reasons”: lack of health insurance hits Latino adults in the US]

So when their son Jesús Fierro Jr. dislocated his shoulder, the couple — who are still paying their own medical bills — opted not to seek care in the United States, heading south to the Mexican border.

Thus, they prevented another account from arriving, at least for one of the family members.

Jesús Fierro Sr. and his family have become “wise buyers” of health care.

When his eldest son dislocated her shoulder, instead of risking another exorbitant bill, they took him to Mexico for treatment.

Lisa Hornak - KHN

The patients:

Jesús Fierro Sr., 48;

Claudia Fierro, 51;

and Jesús Fierro Jr., 17. The family has health insurance from Blue Cross Blue Shield of Texas through Jesús Sr.'s employment at NOV Inc., formerly National Oilwell Varco, an international oil company.

Medical services:

for Jesús Sr., 18 days of hospitalization for a severe coronavirus infection.

For Claudia, less than 24 hours of emergency care after fainting.

For Jesús Jr., in-office care for a dislocated shoulder, without an appointment.

Accounts:

Jesus Sr. was charged $3,894.86.

The total bill was $107,905.80 for COVID-19 treatment.

Claudia was charged $3,252.74, including $202.36 for treatment from an out-of-network doctor.

The total bill was

$13,429.50 for less than one day of care

.

Jesús Jr. was charged $5 (about 100 Mexican pesos) for an outpatient visit that the family paid for in cash.

Service Providers:

Yuma Regional Medical Center, a 406-bed nonprofit hospital in Yuma, Arizona.

He's in the Irons' plan's network.

And a doctor who has a private practice in Mexicali, Mexico, which is obviously not in the network.

Situation analysis:

The Fierros were caught in a situation that more and more Americans find themselves in: they are what some experts define as “functionally uninsured.”

They have insurance, in this case through the work of Jesús Sr., who earns $72,000 a year.

But their health plan is expensive, and they don't have the liquidity—the cash or money in the bank—to pay their “share” of the bill.

The Fierros' medical plan says their out-of-pocket maximum is $8,500 a year for the family.

And in a country where even a quick trip to an emergency room costs a staggering sum, that means a minimal contact with the health system can eat up virtually all of a family's available savings, year after year.

That is why the Fierros chose to leave the system.

Under the terms of his plan, which has a $2,000 family deductible and 20% coinsurance, Jesús Sr. owed $3,894.86 of a total bill of nearly $110,000 for medical care when he had COVID-19 at the end of 2020.

[Five keys for Latino families who need medical coverage in the US]

The Fierros are paying the bill in installments — $140 a month — and still owe more than $2,500.

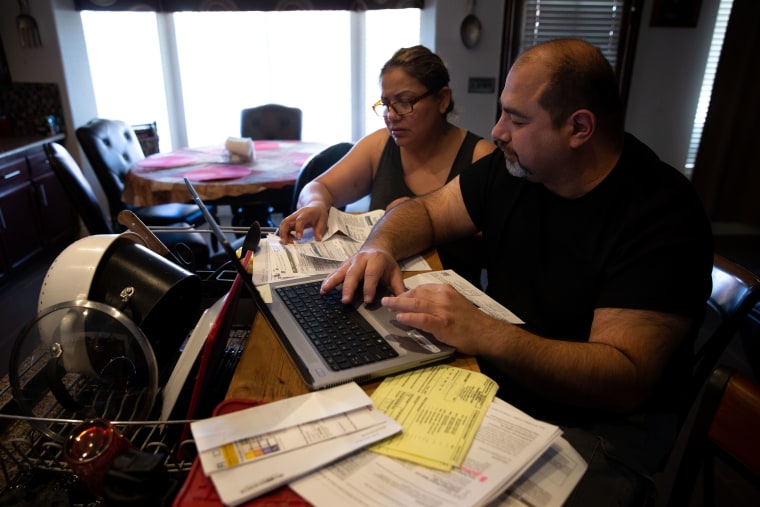

Jesús and Claudia Fierro review their high medical bills.

They say they pay $1,000 a month for their health insurance premiums and yet owed more than $7,000 in deductibles and coinsurance after two medical situations at a local hospital.Lisa Hornak - KHN

In 2020, most insurers agreed to waive cost-sharing payments for COVID-19 treatment after the approval of federal pandemic relief packages that provided emergency funding to hospitals.

But under the law, putting aside treatment costs was optional.

And while Blue Cross Blue Shield of Texas has a policy summary on a website that says it would waive cost-sharing through the end of 2020, the insurer didn't do that with Jesus Sr.'s bill. Carrie Kraft, a spokeswoman for The insurer did not explain why.

(More than two years into the pandemic and with vaccines now widely available to reduce the risk of hospitalization and death, most insurers have returned to charging patients for cost-sharing.)

On January 1, 2021, the Irons' deductible and out-of-pocket maximum were reset.

So when Claudia passed out — a fairly common occurrence that rarely indicates a serious problem — and was rushed to the emergency room by ambulance, the Fierros found themselves with another bill of more than $3,000.

These types of accounts put a lot of stress on the average American family;

Fewer than half of adults have enough savings to cover an unexpected $1,000 expense.

In a recent KFF survey, “unexpected medical bills” ranked second among household budget concerns, behind the price of gas and other transportation costs.

A trip south with a dislocated shoulder

The medical bill for Claudia's fainting destabilized the Fierros' family budget.

“We thought about taking out a second loan on our house,” said Jesús Sr., a Los Angeles native.

When he called the hospital for financial assistance, he said the people he spoke with strongly discouraged him.

“They told me he could apply, but it would only reduce Claudia's bill by $100,” he said.

Domestic workers ask to approve medical insurance for immigrants regardless of their status

April 5, 202202:41

So when Jesus Jr. dislocated his shoulder playing wrestling with his brother, the family headed south.

Jesus Sr. asked his son, "Can you bear the pain for an hour?"

The teenager replied, "Yes."

Father and son made the hour-long drive to Mexicali, Mexico, to the office of Dr. Alfredo Acosta.

The Fierros are not considered “health tourists”.

Jesús Sr. crosses the border to Mexicali every day for his work, and Mexicali is Claudia's hometown.

[There are millions of Latino parents without health insurance. "It's living with stress, with fear," says the mother of a child with cancer]

For years they have traveled to the neighborhood known as La Chinesca to see Acosta, a general practitioner who has treated their youngest son, Fernando, 15, for asthma.

Jesus Jr.'s dislocated shoulder treatment was the first time they sought emergency care in Mexico.

The price was correct and the treatment effective.

A visit to an emergency room in the United States would likely have involved a facility-only fee, expensive X-rays, and perhaps evaluation by an orthopedic specialist, resulting in thousands of dollars in bills.

Acosta repositioned Jesus Jr.'s shoulder so the bones lined up properly, and prescribed ibuprofen for the pain.

The family paid cash at the end of the appointment.

Millions of Americans seek health care in Mexico

Although the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) does not endorse traveling to another country for medical care, the Fierros are among the millions of Americans who do so each year.

Many of them escaping expensive care in the United States, even having health insurance.

Acosta, who is a native of the Mexican state of Sinaloa and a graduate of the Autonomous University of Sinaloa, moved to Mexicali 20 years ago.

He witnessed firsthand the growth of the medical tourism industry.

He sees an average of 14 patients per day (no appointment necessary) with 30-40% arriving from the United States.

He charges $8 for a typical visit.

Most medical debt will be removed from credit reports starting this summer

March 18, 202200:35

In Mexicali, a mile from La Chinesca, where family doctors have their modest offices, there are medical centers that have nothing to envy to those from the north.

These facilities are internationally certified and considered expensive, but are still cheaper than hospitals in the United States.

Resolution:

Both Blue Cross Blue Shield of Texas and Yuma Regional Medical Center refused to discuss the Fierros' bills with KHN, even though Jesús Sr. and Claudia signed written permissions.

In a statement, Machele Headington, a spokeswoman for Yuma Regional Medical Center, said, "Applying for financial support begins with an application, a service that we extended, and still extend, to these patients."

In an email, Kraft, a spokeswoman for Blue Cross Blue Shield of Texas, said, "We understand the frustration our members experience when they receive a bill containing COVID-19 charges that they don't understand or feel may be inappropriate."

The Fierros plan to apply for financial support from the hospital for their outstanding debts.

But Claudia said “never again”.

"I told Jesus: 'If I pass out again, please take me home, don't call an ambulance.'

“We pay a monthly premium of $1,000 for our insurance through my job,” Jesús added.

"We shouldn't have to live with this stress."

The bottom line:

Keep in mind that your deductible “meter” starts over each year and that virtually any emergency care can result in thousands of dollars in bills, and can leave you owing most of your deductible and out-of-pocket maximum.

Also remember that even if it appears that you are not eligible for financial assistance under a hospital's policy, you can still apply and explain your circumstances.

Due to the high cost of care in the country, even many middle-income people qualify.

And many hospitals give their finance departments some wiggle room to adjust bills.

Some patients find that if they offer to pay cash on the spot, the bill can be dramatically reduced.

California will grant health insurance to low-income and undocumented immigrants

April 21, 202202:01

All non-profit hospitals have a legal obligation to help patients: they do not pay taxes in exchange for providing a "community benefit."

Make your case and ask to speak to a supervisor if the first thing you hear is a "no."

[This is how the public charge rule works: how it affects immigrants who receive aid]

For elective procedures, patients can follow the Fierros' lead and become “savvy shoppers” for health care.

Recently, Claudia was told that she had an ulcer and that she needed to have an endoscopy.

The family has been calling different centers and discovered a difference of up to $500, depending on the provider.

They will soon drive to a medical center in California's Central Valley, two hours from home, for the procedure.

The Fierros didn't even consider going back to their local hospital.

“I don't want to say 'hello' and get a $3,000 bill,” Jesus Sr. joked.

Stephanie O'Neill contributed audio to this story. Bill of the Month is a collaborative

KHN

and

NPR investigation

that dissects and explains medical bills.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is the newsroom of KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation), which produces in-depth health journalism. It is one of three major programs of KFF, a nonprofit organization that analyzes the nation's health and public health issues.