Tribute to the dozens of children who died more than a century ago in a boarding school in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Susan Montoya Bryan (AP)

They were taken from the arms of their parents, they changed their names, they cut their hair, they prevented them from speaking their language or practicing their religion and customs, they imposed martial discipline on them.

Many did not survive and were buried next to the schools where they were boarding.

The United States Government has published the first volume of its investigation into the degrading treatment of Native American children in boarding schools and public schools for more than a century.

Among the conclusions, that more than 500 children died in 19 of those boarding schools of horror.

"That number is expected to grow" as the investigation progresses, says the report, which estimates that the tally will rise to "thousands or tens of thousands" of children killed in internments.

The discovery of hundreds of unmarked graves of indigenous children in Canadian boarding schools prompted the United States to launch its own investigation.

The first results have been published this Wednesday by the Department of the Interior, which in the United States is responsible for the management and protection of federally owned territories and also deals with indigenous communities.

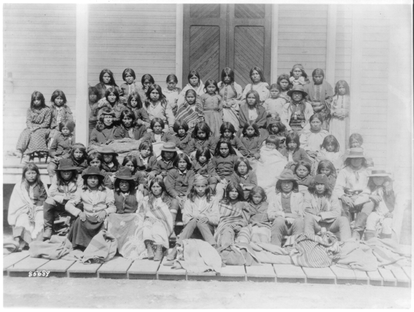

Apache children upon arrival at the Carlisle Indian Boarding School in Pennsylvania.

Research shows that between 1819 and 1969, the federal boarding school system for American Indian children consisted of 408 federal schools in 37 states or then territories, including 21 schools in Alaska and 7 in Hawaii.

The investigation identified marked or unmarked burial sites in 53 schools, and admits that more are likely to turn up.

The report has been presented by the current Secretary of the Interior, Deb Haaland, the first Native American in the position.

"The consequences of federal Indian boarding school policies, including the intergenerational trauma caused by family separation and the cultural eradication inflicted on generations of children as young as four years old, are heartbreaking and undeniable," she said in a statement. release.

Haaland believes that the results of this investigation should be used to give a voice to the victims and their descendants and try to heal the wounds that this action left on the indigenous populations.

Interior Secretary Deb Haaland at an event last February in Jackson, Mississippi.Rogelio V. Solis (AP)

The first volume, 106 pages excluding exhibits, describes how the attempted cultural assimilation of Native American children through the boarding school system actually contributed to the larger goal of dispossessing American Indian tribes of their land and possessions. Native Alaskans and Hawaiians.

"I think this historical context is important to understanding the intent and scale of the federal Indian boarding school system, and why it persisted for 150 years," Bryan Newland, assistant secretary for Indian affairs, says in the report's cover letter.

The document expands on collecting historical testimonies that point in that direction and recalls that hundreds of treaties were signed in the second half of the 19th century with the Native Americans that served to dispossess them of their territories.

Some of them contemplated education, but the report notes that there is abundant evidence that many children were forced to separate from their parents or interned without family consent.

Some natives paid with their lives for resisting having their children taken from them.

One of the annexes shows the location maps of the boarding schools.

The illustration stains the entire map of the United States with black dots, but especially the current states of Oklahoma, New Mexico and Arizona.

Location map of boarding schools for Indian children in the United States (not including Alaska or Hawaii), in a screenshot taken from the official report.

In many of these places, as part of their training, the children worked in livestock, agriculture, poultry farming, milking, fertilization, logging, brick manufacturing;

cooking, making clothes... but the report indicates that they left school with little useful training to integrate into the productive system.

In practice, under the guise of a supposed education, what was being used was child labor.

The federal government often collaborated with religious organizations and institutions that ran boarding schools.

The report documents how a deliberate uprooting policy was carried out.

Not only were they separated from their parents and relatives, but Indians from different tribes were mixed in boarding schools, with the additional purpose that they necessarily had to use English to communicate.

Commissioner for Indian Affairs William A. Jones pointed out in 1902 that one had to be persistent and compared the natives to caged birds.

He said that the first generation wants to fly out of the cage because it retains its instincts, but after several generations the bird will prefer to live in the cage than to fly away.

“The same goes for the Indian boy,” he added, according to the report: “The first wild redskin brought to school resents the loss of freedom and longs to return to his wild home.

His descendants retain some of the habits acquired by their father, but they evolve in each successive generation, setting new rules of conduct, different aspirations and greater desires to be in contact with the dominant race”.

Children picking potatoes at a boarding school for indigenous people.

The investigation has compiled the mistreatment and abuse to which the children were subjected, beyond the separation of their families and forced internment.

“The federal Indian boarding school system deployed systematic militarization and identity-altering methodologies to attempt to assimilate American Indian children,” the report says.

“Rules were often enforced through punishment, including corporal punishment such as solitary confinement, flogging, starvation, whipping, slapping and handcuffing.

(...) Older Indian children were sometimes forced to punish younger ones,” he adds.

Some children tried to escape from boarding schools.

If they were discovered or captured, they received severe punishment.

A history teacher looks at a photo of a 19th-century native boarding school in Santa Fe. Susan Montoya Bryan (AP)

The investigation has already discovered 53 burials in these boarding schools and in 19 of the centers more than 500 child deaths have been identified.

The report does not directly analyze the causes, but it does point out that the entire system of assimilation and uprooting was "traumatic and violent."

Although for now the deaths that have been detected are in the hundreds, the Department of the Interior anticipates that the ongoing investigation "will reveal that the approximate number of Indian children who died in federal Indian boarding schools is in the thousands or tens of thousands", many of they buried in common or unidentified graves.

"The deaths of Indian children while in the care of the Federal Government, or institutions supported by it, led to the breakdown of Indian families and the erosion of Indian tribes," the report concludes.

Subscribe here to the EL PAÍS América newsletter and receive all the key information on current affairs in the region.