Videos show the anguish of the confinement in Shanghai 5:10

Shanghai (CNN) --

Over the hum of the plane's engines, I could hear the stewardess comforting a passenger sitting a couple of rows behind me.

"You're out, and now you're safe," she said warmly.

Our plane had just taken off from Shanghai, a city of gleaming skyscrapers, home to 25 million people who are now slowly being worn away by China's relentless covid-zero regime.

As she approached my row, the stewardess addressed me with the same concerned tone.

"I see you're out with this little guy," she said, looking at my rescue dog, Chairman, asleep in his bag under the seat across from me.

"How did you do it? And how do you feel?" he asked her.

China continues its covid-zero approach as it battles the most widespread outbreak since Wuhan

Chariman spent the flight in his briefcase under his chair.

His words took me by surprise.

As a journalist, I'm usually the one who asks those kinds of questions.

But on this flight, I was one of the few who managed to navigate the complex process of securing a one-way ticket out of Shanghai's oppressive COVID-19 lockdown.

Right now, expats who want to escape Shanghai generally need consular assistance, approval from community leaders for additional non-government covid testing, a registered driver to take them to the airport, and a ticket on a flight, something that is rare, but something even rarer and more difficult is finding a ticket to travel with a pet.

advertising

But above all, the people who leave must promise their community leaders that once they walk through the gates, they won't come back.

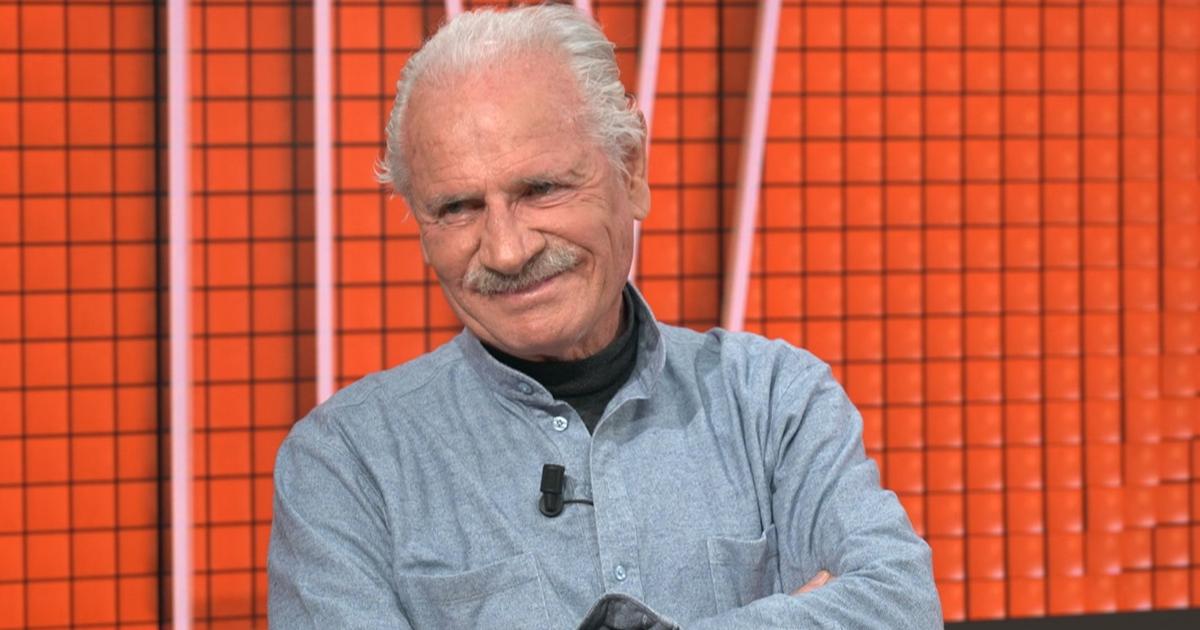

CNN correspondent David Culver leaves Shanghai after living for 50 days under the full covid-19 lockdown.

In Shanghai, deserted roads lead to an empty airport

After 50 days of being in lockdown, I could feel my neighbors watching me from their homes when I walked out of my apartment.

They probably assumed I was being bussed to a government quarantine center like people who had tested positive or found a quick escape route like other expats trying to get out.

In fact, my trip had been planned for several months, long before the maddening lockdown began.

After covering the initial outbreak in Wuhan in January 2020, I stayed in China while it was isolated from the rest of the world.

But after more than two and a half years away from my close-knit Cuban-American family, I needed to return.

The drive from the Xuhui district in central Shanghai to Pudong International Airport, east of the city center, was nothing like what he remembered.

The road covered sidewalks almost desolate, and most of the shops and restaurants were closed, with the shutters drawn and the doors secured with chains and padlocks.

The few people on the streets were mostly wearing hazmat suits, including the police.

Checkpoints lined the route to the airport, and when my driver was stopped, agents spent several minutes inspecting our documents: flight confirmation emails, negative covid tests, even a letter from the US Embassy. .

As we pulled up in front of the terminal, I realized that there were no other cars or passengers in sight, and for a fleeting second I feared that my flight had been cancelled.

The streets were clear outside Shanghai International Airport, which is usually very busy as the city remains on lockdown.

China, a different country before and after the pandemic

The China I am leaving bears little resemblance to the one that welcomed me almost three years ago, but it does remind me of the first major story I covered here.

Months after arriving, my team was sent to Wuhan, in central China, after word spread about a mysterious illness.

That was on January 21, 2020, and within days, the city entered an unprecedented citywide lockdown, the first of many around the world.

This is how David Culver reported in 2020 from Wuhan, when the city was left without a New Year's party and in confinement 2:45

We, along with many others, rushed out, but realizing that we could potentially be exposed, we decided to isolate ourselves in a hotel for 14 days, before quarantine became mandatory.

In those early days, a brief window of unfiltered truth opened before it was closed by Chinese censors.

During that time, we spoke with the families of the victims, who risked their liberties to express their anger at government officials who they say mishandled and covered up the initial outbreak.

Chinese officials maintain that they were transparent from the start.

And just this month, President Xi Jinping reaffirmed and praised his country's zero-Covid efforts, vowing to fight any skeptics and critics of the increasingly controversial policy.

China was one of the first countries to close its borders, build field hospitals, implement mass testing of millions of people and create a sophisticated contact tracing system to track and contain cases, providing a template for other countries as they battled their own. buds.

What is it like to live in Wuhan a year after the lockdown?

Video of 2021 4:18

And for a while it worked.

Even as cases surged around the world, China remained relatively free of Covid-19, and this year it took its pandemic measures to another level, staging the Olympics under the strictest health security apparatus ever staged for a global event.

Reporting in China was notoriously difficult even before covid, but pandemic restrictions meant that every assignment came with the threat of being caught in a quick lockdown or forced into quarantine.

China's battle against covid-19 coincided with the worsening of international relations, particularly its ties with the US. American journalists, like me, received strong visa restrictions: visa periods were shorter and it was eliminated multi-entry access.

So rather than risk staying out of China, many of us stayed.

Take off from confinement and go out in Shanghai

Walking into the airport's eerily quiet Terminal 2 was like advancing to the next level of a video game: a moment of relief overshadowed by anxiety that some kind of unexpected obstacle might take me back to where I started.

The departure board listed only two destinations: Hong Kong and my destination, Amsterdam.

The departure boards were empty except for two destinations for flights that day.

No shops or restaurants were open, even the vending machines had stopped working.

In the far corners of the massive terminal building, departing travelers had left sleeping bags and mounds of trash.

Some were still there, waiting for what I had: a flight out.

At the check-in counter, passengers left rows of carts full of luggage as they waited for hours for attendants in white hazmat suits to show up to check them in.

By the time I got through customs and security, the sun was setting on the dimly lit terminal.

Other passengers, mostly expats, huddled nearby, waiting to board, sharing similar stories.

"We're leaving after 5 years," said one woman.

"We've been here 7 (years)," another passenger replied, pointing to another couple: "They've lived here for like a decade."

Culver took his rescue dog, Chairman, with him on his flight from Shanghai to Amsterdam.

The people I spoke to seemed to have come to the same conclusion: the time they had invested in China's financial hub no longer mattered.

It was time to retreat, cut their losses.

From the window, I could see our plane at the gate and watched ground crews with hazardous materials spraying each other with disinfectant, disinfecting from head to toe after loading the last baggage.

When I finally settled into my seat—with entire rows around me empty—weeks of adrenaline buildup, anxiety, and stress began to subside.

For perhaps the first time since the outbreak began in March, I felt a sense of relief and certainty, albeit tinged with survivor's guilt as the plane took off.

The flight attendants were apparently fascinated by each passenger's "escape story," commenting that they had never had a flight with so many grateful people on board.

Two of them approached my seat as we reached cruising altitude.

One of them said, "You've all had a long few weeks, why don't you get some rest? We'll take you home soon."

The other nodded, then, pointing to her face mask, said, "Oh, and lest you be too surprised, once we land, you'll hardly notice anyone wearing them."

"You are about to enter a whole new world."

Shanghai