The years have not passed in vain for her.

It looks like one of her paintings: an almost abstract figure, blurred by time, with the fat brush strokes that are now her veins marked like furrows on her skin.

More bone than meat.

95 years of life that, however, have left the same clean look with open eyes;

the same radiant smile.

She gives a single kiss on the cheek—Mexican style—and shakes her hand, which her arthritis has turned into a stiff knot of fingers.

Lucinda Urrusti witnessed a time that no longer exists.

First, from the Spanish Civil War and the strangeness of exile.

Later, from the bohemian days of the Federal District;

of gatherings in cafes;

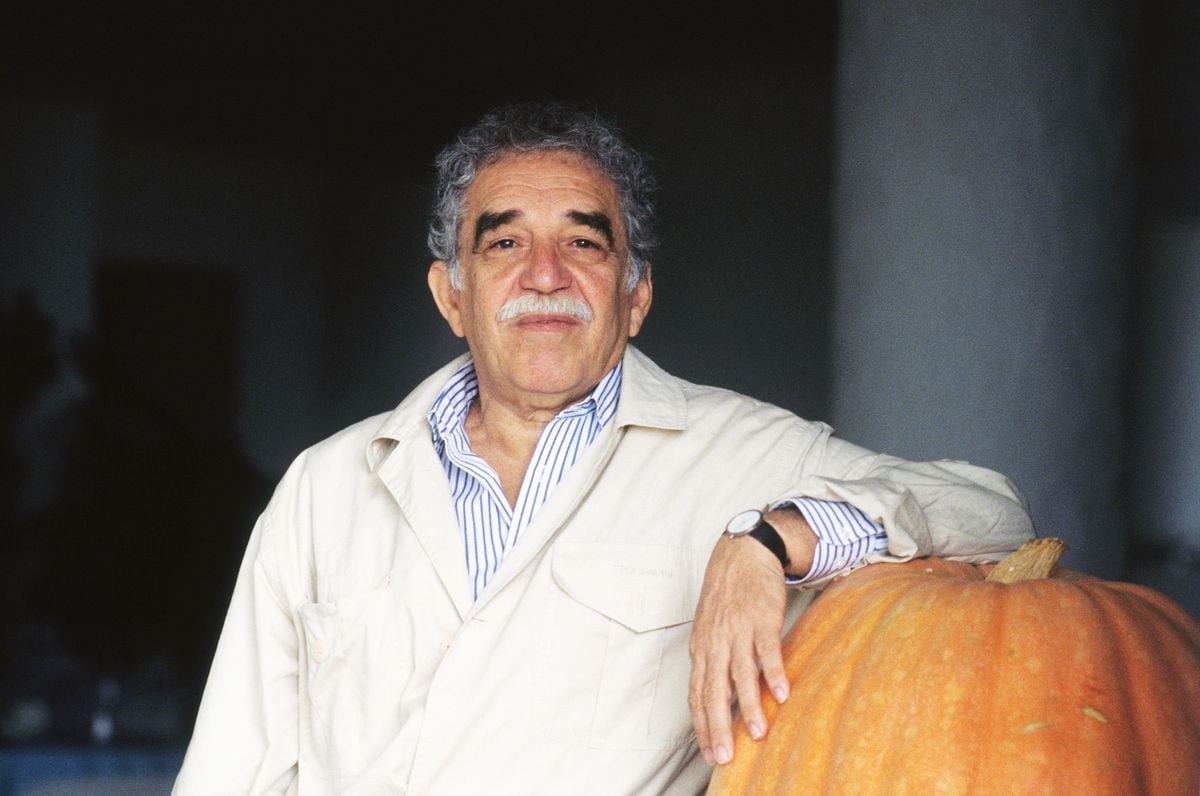

of conversations about poetry, art, literature and politics with her old friends, names that changed history: Gabriel García Márquez, Carlos Fuentes, Rosario Castellanos, Juan Rulfo,

Most of them, in addition to fellow adventurers, were his muses.

And she immortalized them in portraits that are in turn the graphic chronicle of an era.

Things change and now she is portrayed: her nephew, Juan Francisco Urrusti, has directed

Lucinda Urrusti.

Painter

(2020) a documentary that reviews the life and work of her aunt and can be seen these days at the Cineteca Nacional.

The painter Lucinda Urrusti poses at her home in Xochimilco for EL PAÍS, May 2022. Claudia Aréchiga

“The world was smaller, then.

She —as in the novel by her friend Carlos Fuentes— sits alone and remembers, in the long room of her beautiful stone house in Xochimilco, south of Mexico City, where she hides from the world these days.

A TV in the corner is showing the news, but Lucinda doesn't seem to be paying much attention to it.

She has more past than present: she remembers the flight to France when Franco's victory was imminent in Spain;

She remembers crossing the ocean in 1939 aboard the Sinaia, the first ship that President Lázaro Cárdenas sent to help Spanish refugees;

she remembers a life that began in turmoil, an adolescence in a strange country and a youth between oils, ink and paint;

she remembers her applause at her house on November 20, 1975: the date dictator Francisco Franco died.

Although, sometimes, his head plays tricks on him: he confuses his memory, he forgets episodes.

To help her remember, this May morning Juan Francisco Urrusti (67 years old) has come, who sits lovingly by her side.

He lives less than five minutes from his aunt.

Lucinda lives alone, but Paula, who works in the house, helps her with her day-to-day needs.

She can barely move from her room, after two hip surgeries that have left her bedridden or, failing that, in the chair she now rests on with a blanket over her knees.

Her son wants her to move in with him, but the artist doesn't want to leave her home.

"She doesn't say it, but I think she wants to die here, in the same bed where her mother died," says Juan Francisco.

The garden of the house of the painter Lucinda Urrusti, in Xochimilco, this May.

CLAUDIA ARECHIGA

Light pours onto the wooden floor of the room through a window that overlooks the patio, which could very well be Andalusian.

The garden is awash with flowers—pink, red, blue, purple—and an olive tree over 100 years old stands in the center.

The studio where Lucinda painted until six months ago is on the right.

It shines with the orderly mess of artists: tables splattered with paint, acrylic jars, easels, cassettes, shelves with old editions of John Keats, Charles Baudelaire, Saint Teresa of Jesus or Miguel de Unamuno.

On the walls hang paintings by Vicente Rojo and Enrique Climent —who came to portray Lucinda—, friends who, like her, had to go into exile from Spain.

When she got married, she lived with her ex-husband, the late filmmaker Archibaldo Burns, in a house in the most central neighborhood of San Ángel.

Her neighbor was the painter Juan O'Gorman and she began to attend the meetings that the artist organized at her house on Saturday afternoons.

Novelists and poets, painters and philosophers came.

"In those days we were all friends, it was a time when there were no people more important than others", she evokes with a small voice while she poses for the photographs.

The studio where the painter Lucinda Urrusti worked, at her home in Xochimilco, this May.

CLAUDIA ARECHIGA

—I turned around and [Juan] Rulfo was there, sometimes he played dominoes, quietly, quietly... I did a little drawing for him, it wasn't very finished, but I didn't ask him to pose, I more or less watched him.

That Mexico was a wonderful Mexico—he will recall in a scene from the documentary.

He immortalized García Márquez, Fuentes, Paz, Rulfo, but also the Mexican Nobel Peace Prize winner Alfonso García Robles or the historian Beatriz R. de la Fuente.

His style rejected the muralism that prevailed then and leaned towards more surreal pieces, sometimes bordering on impressionism.

Other works of his are three-dimensional or even sculptures, with reliefs and objects that he found on his walks through the streets of the capital.

The painter Lucinda Urrusti, a Spanish exile, draws in her studio, unknown date around the 70s.salazar

In 2012 a book reviewing his career was published.

In it, Carlos Fuentes wrote: “I have followed the artistic development of Lucinda Urrusti since our common youth (…).

The originality of Urrusti, a passenger of both [Paul] Cézanne's dawn and [Claude] Monet's twilight, is that her figures tend to appear and disappear simultaneously.

(...) Thanks to her paintings, I evoke certain Spanish heroics, that goose and suicidal greatness of resistance, which goes from the siege of Numancia to Goya's May 2, to the siege of Madrid by the fascists...".

By then, the painter had already exhibited at the Palace of Fine Arts in Mexico or in New York.

Story of a family exile

Lucinda Urrusti was one of the 25,000 Spaniards who went into exile in Mexico after the Civil War, according to data from the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR).

That part of the story always captivated his nephew Juan Francisco —white hair, red polo shirt, glasses on his lapel and a wide watch on his right wrist—, who from a very young age wanted to explore exile, the roots of his grandparents and fascism. that made them flee from their land.

He was born in Mexico, but he also has Spanish nationality.

More than talking, sometimes he wanders.

He makes long turns before returning to the main road.

Many names and memories that sprout from the main story like branches accumulate in his head.

Perhaps it is professional deformation: he is a professor of cinema at the Cinematographic Training Center.

Juan Francisco Urrusti, film director and nephew of the painter Lucinda Urrusti at his home in Xochimilco, on May 12, 2022. CLAUDIA ARÉCHIGA

As a young man, Juan Francisco Urrusti began recording his grandparents.

He keeps more than four hours of testimonies from each of them, taken over the years.

When he started he had no intention of doing anything with the recordings, but over time the project took the form of the documentary

An Exile: Family Film

(2017), which covers the stories of his ancestors, his life in Spain, the war and the flight.

"It wasn't difficult for me to interview my grandparents... my grandmothers more, for them it was more painful," he says.

Lucinda Urrusti also appears in that film: "At first my aunt didn't want to give me the interview, she didn't want to remember anything about Spain."

The idea of making a movie about Lucinda began in his head in 2015. He was asked to make a 10-minute video about her for an exhibition at the Mexico City Museum.

When he finished, he realized that the artist's life was for much more.

So he began to elaborate leisurely.

He put together material that he already had from his previous documentary and new shots.

In total, he did five interviews between 2012 and 2019 with her.

Lucinda Urrusti.

painter

premiered at a film festival in Poland in 2020. It covers her Mexican times and her work, but leaves out episodes from the artist's life such as the decade she lived in New York —“especially to escape from my grandparents”— or of the death of his son before his 40th birthday.

"My aunt has not recovered from that, from the war yes, but not from the son."

During the month of April, the Cineteca Nacional held a retrospective of the work of Juan Francisco.

As the reporters leave, after a rousing farewell, Lucinda is once again left alone with her memories.

The memories of a movie life that will survive it in the form of documentaries and portraits.

On the left, Lucinda Urrusti with the painter Enrique Climent.

On the right, the artist with Vicente Rojo.

unknown dates.

Courtesy

subscribe here

to the

newsletter

of EL PAÍS México and receive all the informative keys of the current affairs of this country

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/N2CBAPWTK5AYRIQDVR3SFGIKVM)

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/KJKFJLLN25HIBCH7EI7AXP3X44.jpg)