There are two cats.

One is kiwi.

The other, a female named Uber, was about to be called Clona.

The word does not refer to anything related to cloning, but to a drug with anxiolytic properties: clonazepam.

“It saves my life.

I can't live without clonazepam.

When I'm thinking terrible things about myself, about the world, I take a clone and after a while everything is much lighter.

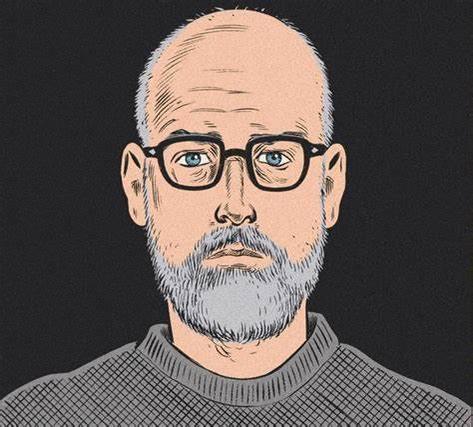

It would be arbitrary —or stigmatizing— to start from that point were it not for the fact that the first thing Cecilia

Gato

Fernández does when she gets into the elevator that takes her to her apartment, a fourth floor apartment in the Villa Crespo neighborhood, Buenos Aires, is talk —not too much in serious—of his “chronic depression”;

or if it weren't for the fact that the "terrible things" she thinks about herself and about the world are at the center of her recent work as an unfortunate engine and reverse inspiration: "

All

my psychoanalysts (...) agreed that being able to draw and write is what who saved me from madness or suicide,” he writes in the epilogue.

The National Fund for the Arts is an Argentine public body that awards prizes to creators from different disciplines.

In 2020, the award was limited for the first time to works of science fiction, fantasy and horror (which generated controversy, since many considered it inappropriate to leave realism out at that time of the beginning of the pandemic), and admitted, also for the first time time, to the graphic novel.

Cecilia

Gato

Fernández, 34, was the winner of that category with a story in which terror is not embodied by diabolical entities but by people, and it does not take place in a frightening dark dimension but in a middle-class apartment.

—I have depression but I am not a sad person.

I use the shield of humor for many things.

When she was poor she didn't say “I'm poor”, she said “I'm rich in lack”.

And I was very poor when I ran away from my mother's house, when I was 20 years old.

I felt completely in danger in that house.

So I ran away.

Life before that escape is what the first volume (there will be three more) of

La sombra de la cucaracha,

the comic that won that FNA award, which was published in Argentina by Historieteca, in Italy by Comicaut, in France by iLatina, and now published in Spain by Astiberri.

With the subtitle

In the house there are ghosts,

it is starred and narrated by a five-year-old girl named Lucía who lives in her paternal grandmother's apartment with her brother, her mother - a psychoanalyst - and her father, a man named Albert.

Alberto —both in life and in the comic— abuses Lucía since she was five years old.

Lucia is Cecilia Fernandez.

Alberto is her father.

The Shadow of the Cockroach

is an autobiographical story.

°

In the living room of the apartment, a bare low-energy bulb sheds an impersonal light.

There is a disproportionate amount of chairs stacked in one corner and several moving boxes.

The desk is a pristine white piece of furniture on which the computer rests.

There is no table to eat, no TV, no books.

The state of transition is something he knows well: since leaving his mother's house, he has moved more than 20 times.

She speaks by going over the side of the nasal septum with the knuckle of her index finger, a gesture that seems to help her thread a story that, perfectly organized in the graphic novel, in orality spreads like trees with pieces that fit together laboriously: the memory of the drawings that she made as a girl derives from the way in which her father lost all his money —”his family had bars, he lost them all”—,

and in a Literature teacher, Graciela Amalio, “brilliant woman, I ask you to name her”, which was fundamental in her taste for writing.

Her parents, whom the graphic novel shows locked in fights of primal violence, separated after the abuse began, although not because of that.

Since then, she saw her father sporadically until, at the age of 10, she refused to continue doing so.

“I felt drowned by how the victims are treated.

That if she wore a 'short', that if she asked for it… ”

"He told me I was shit and left me alone on the street."

I went back home alone, scared, I told my old lady that I didn't want to see him anymore.

I didn't see it for five years and they insisted that I see it when I was 15.

I was with my brother and, with the excuse of giving me a hug, my father began to rub against me and said: "Oh, what small tits you have."

I pushed it.

I screwed it up

And my brother said to me: “Well, it wasn't that big of a deal”.

And I told him: "Let's touch your dick, let's see what you feel."

He talks about the abuse without reticence, but what is at the center—of the story and of the graphic novel—are the collateral effects: the phobias, the nightmares, the indifference of the adults.

—I self-flagellated, and after a cut I made on my leg, in which they had to give me eight stitches, I decided to leave school.

It was very difficult to study with my mother: she had a fixation with making me feel useless.

I was studying and she was yelling at me and swearing at me, so I said: "Enough, I can't take it anymore, I'm leaving this school and looking for a job."

Interior illustration of the book 'The shadow of the cockroach', by Cecilia 'Gato' Fernández.

She got sporadic jobs from which she was almost always fired — “I have problems with authority” —: she made photocopies at a university, was a receptionist at a hairdresser, a clothing salesperson in the store of a Korean woman who was scandalized because she did not wear a bra , waitress and dishwasher in a Chinese restaurant.

In adolescence and early youth they lived an existence with friends, bars, drunkenness, casual relationships ("There is something quite common that when you accept that you were abused you say it a lot. It is also quite normal that you remain asexual or hypersexualized. I at 19 would go out with linings in his bag in case he had an opportunity. Once I picked one up on the bus, I got off with him, I had sex in the street, and he told me: "Ah, but you're a whore." : “And who is here with me?”),

and an increasingly evident vocation: to dedicate himself to comic strips.

So he decided to sign up for a workshop.

Argentina has a powerful tradition in the trade, with names like HG Oesterheld, Solano López, Horacio Altuna, and he decided on Horacio Lalia, a legendary cartoonist.

—He taught me the assembly of the page, the distribution, the narrative.

In the workshop she was the only woman, just like in Trillo's clinic.

Carlos Trillo, who died in 2011, is one of the greatest screenwriters in Argentina, twice winner of the Yellow Kid Award for best international author and the best screenplay award at the Angoulême International Cartoon Festival.

She found in him a sarcastic teacher who made him her favorite.

—He started giving me his scripts to draw.

She immediately became interested in what she was doing.

My first comic was published by him, in Italy.

It was called

Chinese Pizza.

—What did your mother say about that job?

—My mother had a very ambiguous thing.

She would turn off my computer while I was working and she would tell me: “You could do something useful like cleaning the house”.

When I was 20 years old I started having tactile hallucinations.

My phobia is cockroaches, and I felt like cockroaches were crawling up my legs.

I no longer saw my abusive parent, but he called me 14 times a day and talked to me like I was his ex.

She told that to my mother and she said that she was going to write a document for her.

But she never did.

She told me not to pay attention to her, that she was like a guy on the train who masturbates looking at me, that as long as I didn't look at him, everything was fine.

One day she started talking about how much my little brother had suffered because she hadn't had a parental role model, and she said casually: "Well, there was also the issue of Alberto touching you and abusing you."

And I think:

"If she didn't file a complaint, if she didn't do anything, it's because it's not that important."

When I thought that so clearly I said to myself: "I'm very bad."

There I decided to leave, because I felt completely in danger.

“I remember in detail the rape that appears in the book.

I drew her in a panic attack, screaming and crying."

She planned everything and, when she was sure that she was alone to avoid a violent act from her mother, she left.

She took the computer, a bag with books, another with clothes and, like someone who already knows what she wants to do, a photo album.

—I used that album a lot when I made the book.

I wanted my father to be as similar as possible to how he is.

He is one of the two characters that retain the appearance and the real name.

The other is the first psychologist who treated me, who brought up the subject of abuse too quickly, thinking that I was willing to talk, and what I did was not want to talk anymore.

That's why I put his real name.

To how many more girls, abused, has he done the same.

"Did you see your mother after you left that house?"

“I haven't seen her for 11 years.

She locked my room, told my family that I had a drug problem and that's why I left, and told family friends that I was vacationing down south, backpacking with a friend.

I lived in rented rooms, in attics.

I didn't have a weight.

She picked up cigarettes from the street so she could smoke.

She would split noodles for weeks to eat.

I got used.

Everything that follows was a domino: one piece falling on top of another and ending—or continuing—in

The Shadow of the Cockroach.

On his blog, which he hasn't updated for a decade, you can see the drawings he made since 2006, but 2012 marked the end of the blog and the beginning of professionalism: he began to publish in

Fierro

, an emblematic magazine of Argentine comics, and in

Clítoris

, a feminist publication edited by Mariela Acevedo.

—I always had a feminist look without knowing that I was a feminist.

But I spoke ill of the

Clitoris

because she said that feminism was machismo in reverse.

And a friend told me: "You're a fool: you have a magazine that defends those thoughts that you have, and do you criticize it?"

And I said: "Yes, I'm stupid."

I started to get into the

clitoris

, to talk to Mariela.

What happened afterwards was that I felt drowned by so many deaths of women and by the way in which the victims were talked about: if she wore

shorts

, if she asked for it.

I wanted to do something, and since I only knew two feminist activists, Mariela Acevedo and Rocío Fernández Collazo, I called them.

“I spent 11 years without seeing my old lady.

I told her that in all her books I was going to speak ill of her, that she should not read them ”

In 1983 an artistic and political intervention called

Siluetazo

had been carried out in Argentina , which consisted of drawing human silhouettes symbolizing the 30,000 disappeared left by the dictatorship that began in 1976. Rocío Fernández Collazo proposed updating that intervention by drawing silhouettes that represented murdered women.

It was 2015 and Cecilia Fernández made the

flyer

for the first call: she drew a woman on a pool of blood on whose body you could read phrases like "She wore

shorts

", "She had a neckline", "She was alone".

The drawing went viral.

The first call brought together 500 women.

The second, 1,000.

The

Silhouettes

they became the forerunners of the #Niunamenos movement, whose first march took place at the end of that year and spread throughout Latin America.

Fernández continued to live on the run, with precarious jobs, but seemed to have found some places: comics, feminist activism.

In 2016, a group of women accused Cristian Aldana, singer of the band El Otro Yo, of abuse and rape – he would be sentenced to 22 years in prison – and Fernández offered his help to support the complainants.

One day, while accompanying one of the women to make her statement at the Prosecutor's Office, she asked for the first time —after all those years, and all those cuts on her legs, and all those phobias— if it was possible to denounce her parent.

They told him no, that the cause had prescribed.

But soon after, a lawyer assured her that she could.

She was 29 years old when she filed the complaint.

His father, his mother and his brother gave statements, denying that there had been abuse,

or saying they didn't remember.

The case was closed in 2017 due to lack of evidence.

By then, she was already making a book.

The script took him a few months.

Drawing her took him "three painful years, filled with panic attacks, depression, anxiety and a stomach pump."

°

There is little set design in

La sombra de la cucaracha:

the grandmother's apartment, some sidewalks of Buenos Aires, the kindergarten.

A claustrophobic universe that expands into imaginary worlds, sometimes dreamlike (Lucía dreams of being in a brothel where she works as a prostitute), sometimes fantastic (Lucía plays at being a superhero facing monsters with a sword), or in allegories in which cockroaches and sexed anthropomorphic mice appear.

—The mice have to do with sexuality, but on the other hand they are like the repression of memories.

She knew that they were going to be the ones to cover Lucía's eyes so that she wouldn't remember most of the abuse or rape.

Fernández works with explicit violence—the fights between the father and the mother;

Grandma's bestial phrases: “Your mom is a black shit, you don't have to love her” — and with her silence, tensing it into mute vignettes that condense desperation.

But ambiguity is the most flammable element in comics: the mother is a psychoanalyst, cultured, sings and dances with her children, buys them comics, and also tells them erotic stories starring Popeye and Olivia, or ignores all warnings when, for example , the mother of one of her daughter's friends warns her that she has just heard an alarming dialogue between the girls (Lucía lets her playmate understand that her father touches her under her clothes).

The abuse is a permanent gasp, although it is made explicit only twice, the first in six gloomy vignettes: the girl sleeps,

the father is on the other side of the door about to begin his devastation, and at the end of that scene, while the father gets into Lucía's bed, the sexed mice appear and, covering her eyes, tell her: "No. see, for this you are too small”.

Turning the page, Lucía is in kindergarten, listening to music, drawing.

Mariana Eliano

“Both things are part of his life.

Yes, she is an abused girl.

And yes, the next day she goes to the garden, and she sits down to draw with the teacher.

I wanted both things glued together.

Because it is like that in real life.

The second abuse takes place on the dining room table, and there the mice do not blind or repress, they say: “Sorry, Lucía, this time you are going to have to see”, and stay to make sure that her eyes are wide open.

—The only explicit rape there is is that one, which I remember in great detail, and I drew her in the middle of a panic attack, screaming and crying.

It was very difficult.

But I did everything with an intention.

In fact, I was going to publish it in a very large Spanish publisher, and they criticized me for all those decisions.

For example, point of view.

It is always that of the girl, but the most common is that in the autobiographical book the point of view is that of an adult person remembering the past.

I decided that the

voiceover

narrate the present of the protagonist, so that the reader sees only what she can interpret at her age.

It seemed more interesting to me than explaining from an adult perspective.

But the people of Spain told me that it was not understood that after being abused the girl went to kindergarten, that the character of the mother was very ambiguous.

And I said: “Precisely: she is ambiguous!”.

In the end they told me: “What you have to prove with this book is not that you are an abused girl, but that you are a good author”.

Until that moment I had handled the conversation well, but then I started to cry.

I told them, "Excuse me, no, thank you."

And then Astiberri appeared.

“You have to show that you are a good author, not an abused girl,” a large Spanish label told her.

And she left

The first volume of

La sombra de la cucaracha

—whose original Argentine title,

El coup de la cucaracha

, comes from the French expression

le coup de cafard,

which alludes to having a deep depression— ends with Lucía imagining that she is climbing a mountain and, escorted by the mice, she raises her sword that glitters under the stars.

However, what follows that is not effulgent.

—Sometimes I get a little scared that three more books are missing.

But I think the worst is over, because now Lucía's character grows and she is more and more capable of defending herself.

At one point, my old lady started looking for me.

I had to accept that I wanted to have a relationship with her.

I made her promise that she would not read her books, but I told her that if we were going to have a relationship she had to know that I was going to write four books and that I would speak ill of her in all of them.

And she accepted it.

She was terrible in many things, but she also wanted me to tell her: "Hey, I learned to make milanesas."

I make a difference between mother-father-parent-parent.

For a long time they were both my parents.

Even though I now call my parent “mother”, she really is still my parent.

Too much has happened for her to take the place of mother.

But now she is a parent who has good things to offer.

We get along well, and I can say that there is affection.

That's better than nothing.

For my father I feel…revulsion.

Disgust.

-Do you know something about him?

'He lives in a homeless shelter.

She got into debt, she was left on the street.

"How do you know he lives in a shelter?"

—Because when he went to testify for a lawsuit he wanted to do to us, he had an address in a shelter.

"What trial?"

—He wanted to file a complaint against my brother and me for abandoning a person.

In Argentina, copies of

La sombra de la cucaracha

that were offered for pre-sale were delivered with a fanzine that included a series of self-portraits by Fernández.

On the back cover he had this inscription: “For me, the self-portrait is a relief therapy.

It's not in my plans to let myself drown."

—Why is the girl in the cartoon called Lucía?

"To put a little distance," he answers quickly.

And immediately after:

“Lucia is my name.

My name is Cecilia Lucia.

But no one calls me that anymore.

From which it follows that that is what they called it.

'The shadow of the cockroach.

There are ghosts in the house.

Fernandez cat.

Astiberri, 2022. 104 pages.

14 euros.

It is published on May 26.

You can follow BABELIA on

and

, or sign up here to receive

our weekly newsletter

.

Exclusive content for subscribers

read without limits

subscribe

I'm already a subscriber

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/UGT3A2CDINB3LN3NMTZ4RJJOTU.jpg)