Holder of a doctorate from the EHESS after completing a thesis under the supervision of Pierre Bourdieu, Nathalie Heinich is a sociologist, specialist in contemporary art. She is the author of

The Paradigm of Contemporary Art, Folio

, 2022.

LE FIGARO.- In your book, you suggest considering contemporary art no longer as an artistic genre, but as a new paradigm. What is the difference ? What does this change?

Nathalie HEINICH.-

The first thing to bear in mind is that contemporary art should be considered not as a period but as a genre.

This is what I had already shown in my first book on contemporary art,

The Triple Game of Contemporary Art,

published in 1998 by Minuit.

I left this chronological approach, which is the most common, by explaining that contemporary art is characterized by properties that are not limited to the fact of being produced at a given moment in time.

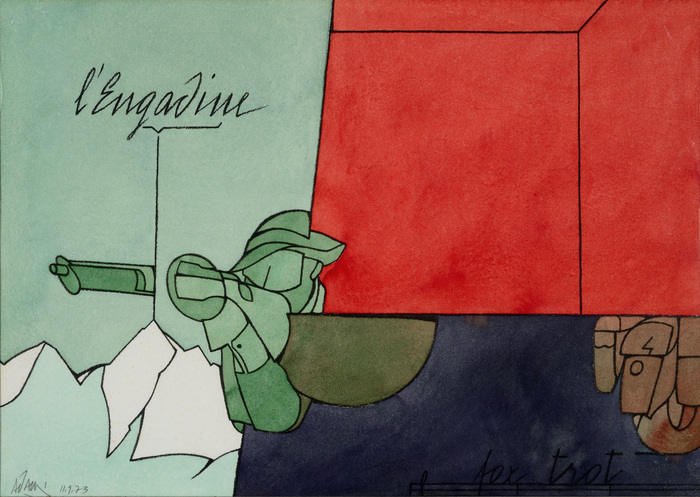

Thus, in the current period, works can be produced and exhibited which are at least as much part of what is called modern art – even classical art – as of contemporary art.

Conversely, works typical of what is called contemporary art may have been produced in much earlier periods.

The first deviation from the common sense conception was therefore to move away from a chronological conception.

Then, by going deeper into the question, I understood that the notion of artistic genre is not enough because it is too limited to the formal characteristics of the works, as for the classic genres of still life, portrait, landscape, painting of history, etc.

However, a much broader notion is needed to understand the way in which works circulate in contemporary art, because the organization of the entire art world has been totally modified there.

It is this extension beyond the work, towards the processes of production, mediation and reception that I have tried to systematize in the notion of paradigm, borrowed from the philosopher of science Thomas Kuhn.

This public sector of contemporary art allows artists to make a career in institutions by hardly going through the commercial circuit.

Nathalie Heinich

The evolution of artists' careers, their fame, is done jointly via the commercial sector and via institutional selection. Globalization and Contemporary Art are one?

No, because there is contemporary art that is not globalized, and there are forms of globalization that have nothing to do with art.

More precisely, there is an important institutional dimension in contemporary art which is present in most Western countries but which has been particularly developed in France.

In the 1980s, the policy led by Jack Lang made it possible to create a large number of institutions dedicated to contemporary art: Frac, art centers, museums of contemporary art.

This public sector of contemporary art allows artists to make a career in institutions by hardly going through the commercial circuit, which is much less the case in other countries.

How do you explain that in our country the public sector has "laid its hands" on contemporary art?

France was at the forefront of a heritage policy in the 19th century, already in public institutions.

It also innovated in the 1960s with the policy of André Malraux, in particular the cultural centres, and the idea that the arts had to be decompartmentalized and made more accessible.

The former Secretariat of State for Fine Arts has also become the Ministry of Culture.

And then, we had a whole series of initiatives to help artistic creation via the 1% system (since the 1950s), public commissions, scholarships and aid of all kinds... This tradition of cultural intervention is linked to the idea that the State must support innovative works, works which are of general interest because they are of high quality,

until the market is able to absorb them and allow them to circulate.

Indeed, when we are dealing with original works, avant-garde works, they take a certain time to be sufficiently appreciated to be profitable, and the State will therefore replace the market which is not able to economically support innovative proposals.

This principle of support for innovative creation obviously has its merits, but also sometimes perverse effects due to over-institutionalization, as pointed out in particular by Marc Fumaroli in his time.

But initially, the intention was to both help innovative artists and promote cultural democratization.

we are dealing with original works, avant-garde works, they take a certain time to be sufficiently appreciated to be able to be profitable, and the State will therefore replace the market which is not capable of supporting economic innovative proposals.

This principle of support for innovative creation obviously has its merits, but also sometimes perverse effects due to over-institutionalization, as pointed out in particular by Marc Fumaroli in his time.

But initially, the intention was to both help innovative artists and promote cultural democratization.

we are dealing with original works, avant-garde works, they take a certain time to be sufficiently appreciated to be able to be profitable, and the State will therefore replace the market which is not capable of supporting economic innovative proposals.

This principle of support for innovative creation obviously has its merits, but also sometimes perverse effects due to over-institutionalization, as pointed out in particular by Marc Fumaroli in his time.

But initially, the intention was to both help innovative artists and promote cultural democratization.

is not able to economically support innovative proposals.

This principle of support for innovative creation obviously has its merits, but also sometimes perverse effects due to over-institutionalization, as pointed out in particular by Marc Fumaroli in his time.

But initially, the intention was to both help innovative artists and promote cultural democratization.

is not able to economically support innovative proposals.

This principle of support for innovative creation obviously has its merits, but also sometimes perverse effects due to over-institutionalization, as pointed out in particular by Marc Fumaroli in his time.

But initially, the intention was to both help innovative artists and promote cultural democratization.

Once the transgressive is recognized and encouraged by the institutions, he must become ever more transgressive in order to remain transgressive.

Nathalie Heinich

You describe a system that lives in a vacuum, partly supported by an above-ground international class, which considers the work of art as a financial product and which uses museums as an artistic certification. Isn't it paradoxical when one wants to be transgressive?

This is the idea that I developed in

Le triple jeu

speaking of the “permissive paradox” once the transgressive is recognized and encouraged by the institutions, he must become ever more transgressive in order to remain transgressive.

There is thus produced a kind of headlong rush into transgression, which can be clearly seen in the radicalization of a certain number of artists' proposals – this is typically what sociologists call a perverse effect.

Hence, since the 1990s in France, what is called the "contemporary art crisis", that is to say a virulent challenge to contemporary art not only by people belonging to the right, reactionaries or conservatives, but also by people coming from the left but who, generally in the name of modern art (and no longer classical art), criticize what

they consider as drifts specific to contemporary art.

This is a completely new configuration, since we are no longer in the quarrel between the ancients and the moderns.

Do you think this headlong rush that you describe will continue, or will contemporary art regulate itself? Won't a certain weariness on the part of the spectator lead to a return to “puritanism”?

It all depends on the spectators, because obviously there is not just one type of spectator.

Depending on where you stand in relation to contemporary art, you don't have the same vision at all.

Those who are distant from it have the feeling that it is always the same thing, always the same type of transgressions, that in the end it goes around in circles.

On the other hand those who are inside this world see above all the differences limits, because it is and that which interests them, and they thus have the feeling of a renewal.

This is what I explain in the conclusion of the book: for some it is an art fundamentally in crisis because transgression cannot be renewed eternally, we cannot invent new forms of transgression all the time, while for'

others it never ceases to renew itself.

But they are very different types of spectators, and that does not prevent this world from continuing to function: there are always art critics, exhibition curators, museum curators, gallery owners, collectors.

So in fact the paradigm of contemporary art is not exhausted, even if from the outside one can have the feeling that the repertoire is not renewed.

Contemporary art also marks the decline of exhibitions, to the benefit of fairs, temporary installations... As a result, transactions are more or less concealed...

What is happening is not so much a decline in exhibitions, because there are always plenty of them in galleries, and museums, but it is a decline in painting salons.

The world of modern art was built on painting salons, with the Salons of the Impressionists, the Independents, the Salon d'Automne, etc.

where galleries and collectors discovered new artists.

Today the painting salons are totally disqualified because they are essentially reserved for modern art, and therefore not interesting for specialists in contemporary art.

What has become very important is exhibitions in galleries, in museums (or in art centers for those who are more in the public sector), and above all the combination of fairs and biennials.

The fairs are commercial because works are sold there, whereas biennials are purely cultural, the works are not for sale there, they are structures dependent on the public authorities which allow exhibition curators to present, what they consider the most interesting in current art.

It is this system which succeeded the system of salons.

There is also a speculative dimension which appeared in the 1990s. I explain in chapter 3 of the

Paradigm of contemporary art

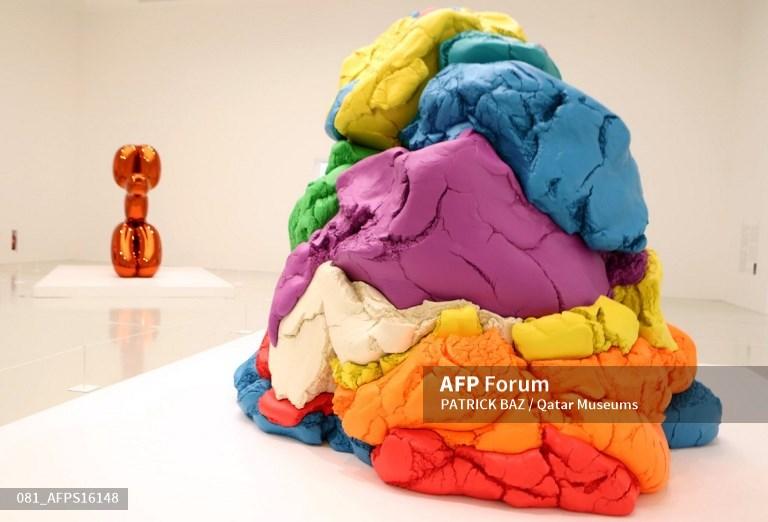

why the new world of traders, born of finance, of the financialization of capitalism, has allowed the appearance of great fortunes among young and relatively uneducated people, who need to spend their money and do so by investing in a certain type works of contemporary art, very immediately comprehensible - hence the fashion for the Young British Artists, Jeff Koons, etc., with a little concealed speculative dimension.

However, it is frowned upon in the art world to buy works for money: it is an investment which has never been displayed as such, which has always been considered as the fruit of a taste cultivated.

From the financial point of view it can play the role of an investment like any other, but its particularity is not to be considered as an investment.

of

elsewhere, collectors identified by galleries as having a purely speculative logic are generally avoided.

But that does not mean that the transactions are concealed, except in certain very specific cases of very high auction sales where the buyer does not make himself known, probably for reasons linked to a speculative strategy.

What is proposed by the artist is something temporary, of the order of a show, like in the installations, where the work is no longer in the object.

Nathalie Heinich

With contemporary art, we go from the work to the scenography. What does this change in our relationship to art?

The characteristic of a contemporary work of art is that it integrates not only the object proposed by the artist, if there is an object, but also its context of presentation, and the effects it has on the context: it is a global work, beyond the object, and this is the big difference with the classical paradigm and the modern paradigm.

This induces a scenography in the sense that, more and more, what is proposed by the artist is something temporary, of the order of a show, as in the installations, where the work is no longer in the object since the object can go in the trash once the installation has been dismantled: it is in the device that the artist proposes, analogous in certain cases to forms of proposals linked to live performance.

Etc'

is particularly the case in the performance of an artist, which is at the limit of theater or dance.

This shift towards scenographic forms has all sorts of practical consequences, in particular the fact that institutions can pay the artist to create the installation, without buying the installation itself.

There are all sorts of economic or practical modifications, also linked to the question of the transport of works, the question of insurance, of restoration, which are part of this global modification of the art world brought about by the paradigm of contemporary art.

in particular the fact that institutions can pay the artist to carry out the installation, without buying the installation itself.

There are all sorts of economic or practical modifications, also linked to the question of the transport of works, the question of insurance, of restoration, which are part of this global modification of the art world brought about by the paradigm of contemporary art.

in particular the fact that institutions can pay the artist to carry out the installation, without buying the installation itself.

There are all sorts of economic or practical modifications, also linked to the question of the transport of works, the question of insurance, of restoration, which are part of this global modification of the art world brought about by the paradigm of contemporary art.

Nathalie Heinich, The paradigm of contemporary art, 2022, Gallimard, 480 p.

Gallimard

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/B4T7XCN2ORDQLGNNVCIV4QQYC4.jpg)

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/3I74UEXLYRBBRPGPSGWNN6WXH4.jpg)