Leon Trotsky harangues the Russian soldiers.

Image from 'L'Illustrazione Italiana', year XLIX, No 36, September 3, 1922. DE AGOSTINI PICTURE LIBRARY (GETTY IMAGES)

In August 2020, eighty years after the assassination of Lev Davídovich Bronstein, Trotsky, at the hands of the Stalinist agent Ramón Mercader, I received a surprising number of requests for interviews, invitations to write articles and also calls to participate in debate tables on that historical event.

At the same time, I received various reports from different parts of the world, but especially from Latin American countries, dedicated to recalling and assessing, with the perspective of the time that has elapsed, the crime of August 20, 1940 in the house of the exiled prophet, in the Mexican delegation from Coyoacán.

What historical curiosity, what claim of the present could have provoked that renewed and intense interest in the figure of Trotsky almost a century after his death?

In a globalized, digitized world, polarized in the worst way, dominated by rampant and triumphant liberalism and, to top it off, hit by a pandemic of biblical proportions that put (and continues to have) the destiny of humanity in check, what there was such an expectation to recover the fate of a Soviet revolutionary of the last century that, by the way,

had he been the loser in a political and personal dispute that was intended to end with his assassination?

What could the crime of 1940 and the figure of the victim of a furious ice-axe attack ordered from the Soviet Kremlin tell us at this point in these historical and social coordinates?[1] Did Trotsky and his thought still have validity, the ability to transmit something useful for our turbulent present, three decades after the disappearance of the Soviet Union that he had helped to found?

The verification that certain sectors of the thought, politics and art of these times still feel summoned by the vital events and the philosophical and political contributions of Lev Davídovich Trotsky may have a first correlate (and many others).

And that first elucidation perhaps reaffirms (at least I think so) that, defeated in the political arena, the exile turned out to be a battered winner in the historical dispute projected into the future;

from the latter, unlike his assassins, he has come out as a symbol of resistance, coherence and, for his followers, even as the incarnation of a possibility of realizing utopia.

And this peculiar process has occurred not only because of the way he was killed, but, of course,

for the same reasons that led Iósif Stalin to liquidate him physically and the Stalinists of the world to erase him even from photos, historical studies and academic recounts.

A Stalin and some Stalinists who – it will always have to be repeated – not only executed the person of Trotsky and tried to do it with his ideas, but also took charge of liquidating the possibility of a more just, democratic and free society with blows of socialist authoritarianism. that at one time they proposed to found men like Lev Davidovich.

The same man who, as a young man just out of the Menshevik party, in 1905 went so far as to say that “for the proletariat, democracy is in all circumstances a political necessity;

for the capitalist bourgeoisie it is, in certain circumstances, a political inevitability”… key sentence that,

It should not surprise us, then, that the recovery and publication, for the first time in Spanish, of a text by Lev Davídovich (or León Trotsky) provokes justified interest.

Because, within the voluminous bibliography of the man who even wrote a detailed autobiography (

My life,

published in 1930, a work that closes with the episode of his exile to the eastern Soviet Union, the beginning of his definitive exile), the pages of

La flight from Siberia in a reindeer sleigh

(in the original,

Tudá i obratno

; that is,

Round trip

) serve to give us the weapons of a young writer and revolutionary, whose image, so well known, is rounded out even more with this curious work.

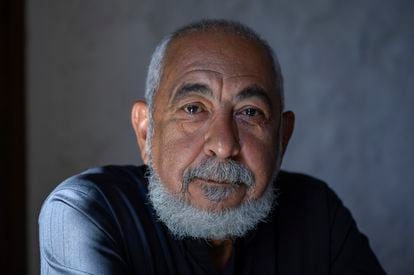

Leonardo Padura, in May 2022. Pedro Puente Hoyos (EFE)

And it is that The Escape from Siberia, which Davídovich published in 1907 under the pseudonym of N. Trotsky under the Shipovnik imprint, is a booklet that, due to the closeness between the narrated events and their writing – due to the historical situation in which those events occur events, the age and the degree of political commitment of its author at the moment of living what he narrates and, immediately, deciding to capture it–, he gives us a young Trotsky almost in its purest form.

And this in all facets of him: as a politician, as a writer, as a man of culture and, above all, as a human being.

Therefore, from now on it seems necessary to warn that the pages of

The Escape from Siberia

narrate the personal and dramatic story of Davídovich's second exile to the penal colonies of Siberia (his first deportation, lived between 1900 and 1902, had been a period of political and philosophical growth from which he emerged strengthened and even with the pseudonym of Trotsky with which he would later be known) and the tremendous incidents of his almost immediate escape, this time in the winter of 1907. An adventure lived as a result of the so-called "Soviet Case", when the author, along with fourteen other deputies, was tried and sentenced to indefinite deportation and loss of civil rights[2] as a result of the events that occurred in St. Petersburg around the creation and operation of the Council or Soviet of Workers' Delegates, which Trotsky himself led during its weeks of existence, in the final months of the convulsive year of 1905.

The text, then, refers us to a time when the political and philosophical life of its author were at the center of the debates that would define the directions along which his revolutionary thought and action would later move, heated by that vertiginous experience of the first Soviet in history, in 1905, matured in the fruitful exile that he would live from 1907 and materialized in the October Revolution of 1917, during which he would once again be a protagonist.

And from this trajectory he emerges as one of the central figures in the political process that led to the founding of the Soviet Union and the always controversial establishment of a dictatorship of the proletariat.

The Lev Davidovich of today is the impulsive, wild-haired revolutionary who, in the words of his renowned biographer Isaac Deutscher, embodied the highest degree of “maturity” that the [revolutionary] movement had hitherto reached in its broader aspirations: in formulating the goals of the revolution, Trotsky went further than [Iuli] Martov and Lenin, and was therefore better prepared to play an active role in events.

An infallible political instinct had taken him, at opportune moments, to the nerve centers and the foci of revolution.[3]

In that trance, we also see the thinker who soon writes

Results and perspectives

.

The driving forces of the revolution, his main work of the period, where he presents the fundamental statements of future Trotskyism, including the theory of Permanent Revolution.[4]

In those pages, Trotsky himself warns, with the political lucidity that often (not always) accompanies him:

At the time of its dictatorship, […] the working class will have to clear its mind of false bourgeois theories and experiences, and purge its ranks of backward-looking political and revolutionary charlatans… But this intricate task cannot be solved by putting above from the proletariat to a few chosen persons… or to a single person invested with the power to liquidate and degrade.[5]

The pages of

The Escape from Siberia

, however, do not become a political statement or a work of propaganda or reflection: above all, they relate the personal and dramatic story (recorded very succinctly in

My Life

) that gives us an observer Trotsky, profound, human, at times ironic, who looks around and expresses a state of mind or takes a photograph of an environment that, without a doubt, reveals itself to be extreme, exotic, almost inhuman.

* * *

Conceived in two perfectly differentiated parts ('The way out' and 'The way back'), the testimony of these experiences follows the entire process of transferring Trotsky and the other fourteen convicted for their leading role in the 1905 Revolution to exile. Indeed, the story covers from the release of the prison of the Peter and Paul Fortress, in St. Petersburg, on January 3, 1907 (a compound where he had spent the entire year 1906 dedicated to writing) to the arrival in the town of Beriozov , on February 12, 1907, the penultimate stop of a transit that was to end where the sentence would be served, the remote town of Obdorsk, a place located several degrees north of the Arctic Circle, more than 1,500 versts from the station of nearest railroad and 800 from a telegraph station, according to the writer himself.[6]

Next, and with a visible change in style and narrative conception, the book recounts, always in the first person, the chronicle of Trotsky's escape from Beryozov (where he manages to stay, feigning illness, while his companions continue on).

With his grotesque guide, he will head from there to the Southwest, in search of the first railway station in the mining area of the Urals to finalize his return to Saint Petersburg, from where he will go into exile where, a few months later, he would have his first meeting – the one that perhaps from the first moment was going to define his fate – with the ex-seminarian Iósif Stalin.

The first element that distinguishes the conception of

The Escape from Siberia

lies in the fact that the initial half is assembled with the letters that Trotsky wrote to his wife, Natalia Sedova, over forty exhausting days, while he and his companions carried out the journey to exile.

This epistolary strategy, almost like a travel diary written on the fly, defines the style and meaning of the text, since what is narrated reflects a recently lived reality in which there is no possible knowledge of the future, as would have happened with the writing evocative of the already known.

The story, which begins with a letter dated January 3, 1907, when Trotsky and his fellow convicts were transferred to the provisional prison in St. Petersburg, extends to the letter of February 12, already written in Beriozov, where, on the advice from a doctor the author feigns an attack of sciatica in order to remain there and attempt to escape.

In all this time and journey, which begins by train and (since the end of January, in the town of Tyumen) continues by horse-drawn sleigh, Trotsky and the other condemned do not know the final destination that has been assigned to them and when they will reach it. , so an expectation close to suspense is created.

As expected in the case of correspondence that could be reviewed, at no time does the author reveal his escape plans, although he speaks of the predictable escapes of convicted persons that occur with high frequency.

“To get an idea about the percentage of escapees, it is enough to know that of the four hundred and fifty exiles in a certain area of Tobolsk, only one hundred remain.

The only ones who don't run away are the lazy ones,” he comments at one point.

Nevertheless,

The flight from Siberia

appears as an unexpected crack that allows us to peek into the intimate personality of the full-time political and revolutionary man and his relationship with the human condition.

It also constitutes a sample of his literary abilities (not in vain for a time he was nicknamed "La Pluma") and, as a climax, its publication, for the first time in Spanish, can be a tribute to the memory of a thinker, writer and fighter murdered more than eighty years ago who, in today's world of so many faithless, still makes some think that utopia is possible.

Or, at least, necessary.

In Mantilla, September 2021

[1] Allusion to the compact mountaineering tool used as a murder weapon by Ramón Mercader.

[N.

of E.]

[2] Two or three years earlier, the additional punishment of forty-five lashes for the convicted person had been abolished.

[3] Isaac Deutscher, Trotsky, the armed prophet, Mexico, Era, 1966, pp.

118-119.

[4] Ibid., p.

146.

[5] cit.

ibid., p.

96.

[6] The verst is equal to 1066.8 m, so, in a rough calculation, we can assimilate it to 1 km.

'The flight from Siberia in a reindeer sleigh

', by Leon Trotsky.

Presentation of Leonardo Padura.

Intellectual key, 2022. 128 pages.

14 euros.

You can follow BABELIA on

and

, or sign up here to receive

our weekly newsletter

.

Exclusive content for subscribers

read without limits

subscribe

I'm already a subscriber

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/T64LVSQLMRBDPKNF5NQ2IQUK4E.jpg)

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/TY47FSPP2RB4BEVHHZRVRO4QLY.jpg)

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/AZ5ZY2PCPRQBCHZFMVQZQT5X2E.jpg)